Korean Circ J.

2018 Sep;48(9):792-812. 10.4070/kcj.2018.0249.

Unsettled Issues and Future Directions for Research on Cardiovascular Diseases in Women

- Affiliations

-

- 1CHARITÉ Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Institute of Gender in Medicine and CCR, and DZHK (partner site Berlin), Berlin, Germany. vera.regitz-zagrosek@charite.de

- KMID: 2418805

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2018.0249

Abstract

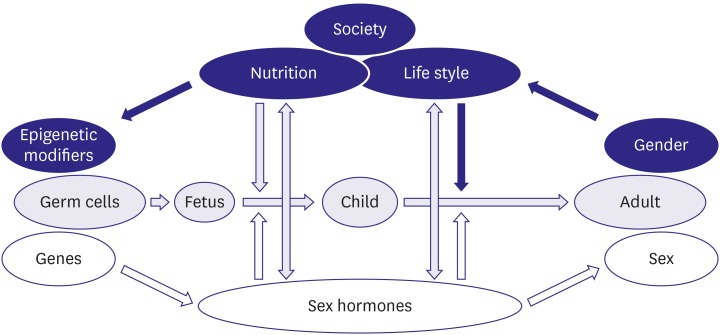

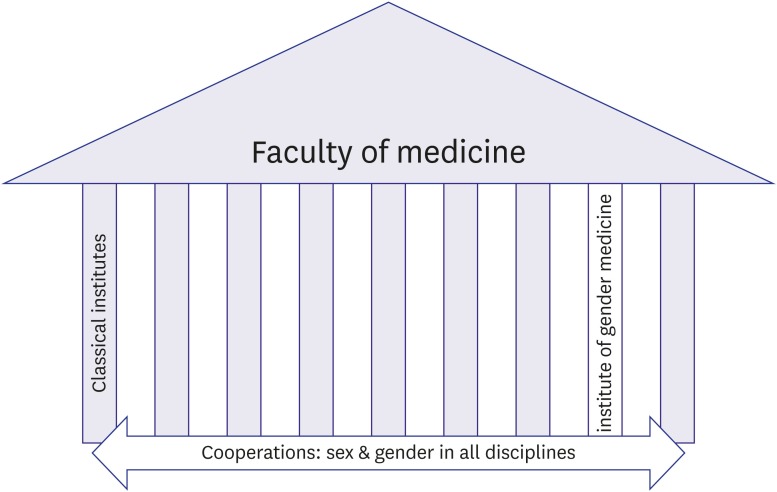

- Biological sex (being female or male) significantly influences the course of disease. This simple fact must be considered in all cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. However, major gaps in knowledge about and awareness of cardiovascular disease in women still impede the implementation of sex-specific strategies. Among the gaps are a lack of understanding of the pathophysiology of women-biased coronary artery disease syndromes (spasms, dissections, Takotsubo syndrome), sex differences in cardiomyopathies and heart failure, a higher prevalence of cardiomyopathies with sarcomeric mutations in men, a higher prevalence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in women, and sex-specific disease mechanisms, as well as sex differences in sudden cardiac arrest and long QT syndrome. Basic research strategies must do more to include female-specific aspects of disease such as the genetic imbalance of 2 versus one X chromosome and the effects of sex hormones. Drug therapy in women also needs more attention. Furthermore, pregnancy-associated cardiovascular disease must be considered a potential risk factor in women, including pregnancy-related coronary artery dissection, preeclampsia, and peripartum cardiomyopathy. Finally, the sociocultural dimension of gender should be included in research efforts. The organization of gender medicine must be established as a cross-sectional discipline but also as a centered structure with its own research resources, methods, and questions.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Gender Difference of Cardiac Remodeling in University Athletes: Results from 2015 Gwangju Summer Universiade

Hyun Ju Yoon, Kye Hun Kim, Kyle Hornsby, Jae Hyeong Park, Hyukjin Park, Hyung Yoon Kim, Jae Yeong Cho, Youngkeun Ahn, Myung Ho Jeong, Jeong Gwan Cho

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(5):426-438. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0484.

Reference

-

1. Oertelt-Prigione S, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender aspects in clinical medicine. London: Springer Verlag;2011.2. EUGenMed Cardiovascular Clinical Study Group. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Oertelt-Prigione S, et al. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:24–34. PMID: 26530104.3. Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:2128–2132. PMID: 18036449.4. Puymirat E, Simon T, Steg PG, et al. Association of changes in clinical characteristics and management with improvement in survival among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012; 308:998–1006. PMID: 22928184.5. Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, et al. EUROASPIRE III: a survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009; 16:121–137. PMID: 19287307.6. Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, Hein HO, Vestbo J. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. BMJ. 1998; 316:1043–1047. PMID: 9552903.7. Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Corti R, et al. Ischaemic heart disease in women: are there sex differences in pathophysiology and risk factors? Position paper from the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2011; 90:9–17. PMID: 21159671.8. Staessen JA, Wang JG, Thijs L. Cardiovascular protection and blood pressure reduction: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2001; 358:1305–1315. PMID: 11684211.9. Coylewright M, Reckelhoff JF, Ouyang P. Menopause and hypertension: an age-old debate. Hypertension. 2008; 51:952–959. PMID: 18259027.10. Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1291–1297. PMID: 11794147.11. Silber TC, Tweet MS, Bowman MJ, Hayes SN, Squires RW. Cardiac rehabilitation after spontaneous coronary artery dissection. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2015; 35:328–333. PMID: 25730096.12. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004; 364:937–952. PMID: 15364185.13. Barrett-Connor EL, Cohn BA, Wingard DL, Edelstein SL. Why is diabetes mellitus a stronger risk factor for fatal ischemic heart disease in women than in men? The Rancho Bernardo Study. JAMA. 1991; 265:627–631. PMID: 1987413.14. Donahue RP, Rejman K, Rafalson LB, Dmochowski J, Stranges S, Trevisan M. Sex differences in endothelial function markers before conversion to pre-diabetes: does the clock start ticking earlier among women? The Western New York Study. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30:354–359. PMID: 17259507.15. Kalyani RR, Lazo M, Ouyang P, et al. Sex differences in diabetes and risk of incident coronary artery disease in healthy young and middle-aged adults. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37:830–838. PMID: 24178997.16. Parashar S, Rumsfeld JS, Reid KJ, et al. Impact of depression on sex differences in outcome after myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009; 2:33–40. PMID: 20031810.17. Xu X, Bao H, Strait K, et al. Sex differences in perceived stress and early recovery in young and middle-aged patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015; 131:614–623. PMID: 25679303.18. Hoffmann B, Moebus S, Möhlenkamp S, et al. Residential exposure to traffic is associated with coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2007; 116:489–496. PMID: 17638927.19. Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:1545–1588. PMID: 24503673.20. Shaw LJ, Bugiardini R, Merz CN. Women and ischemic heart disease: evolving knowledge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 54:1561–1575. PMID: 19833255.21. Hochman JS, McCabe CH, Stone PH, et al. Outcome and profile of women and men presenting with acute coronary syndromes: a report from TIMI IIIB. TIMI Investigators. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997; 30:141–148. PMID: 9207635.22. Gehrie ER, Reynolds HR, Chen AY, et al. Characterization and outcomes of women and men with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary artery disease: results from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) quality improvement initiative. Am Heart J. 2009; 158:688–694. PMID: 19781432.23. Lansky AJ, Ng VG, Maehara A, et al. Gender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012; 5:S62–S72. PMID: 22421232.24. Yahagi K, Davis HR, Arbustini E, Virmani R. Sex differences in coronary artery disease: pathological observations. Atherosclerosis. 2015; 239:260–267. PMID: 25634157.25. Reynolds HR, Srichai MB, Iqbal SN, et al. Mechanisms of myocardial infarction in women without angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011; 124:1414–1425. PMID: 21900087.26. Camici PG, d'Amati G, Rimoldi O. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: mechanisms and functional assessment. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015; 12:48–62. PMID: 25311229.27. Herrmann J, Kaski JC, Lerman A. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in the clinical setting: from mystery to reality. Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:2771–2782b. PMID: 22915165.28. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012; 126:2020–2035. PMID: 22923432.29. Johnston N, Jönelid B, Christersson C, et al. Effect of gender on patients with ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015; 115:1661–1666. PMID: 25900352.30. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:3147–3197. PMID: 21873418.31. Komamura K, Fukui M, Iwasaku T, Hirotani S, Masuyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. World J Cardiol. 2014; 6:602–609. PMID: 25068020.32. Sharkey SW, Maron BJ. Epidemiology and clinical profile of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2014; 78:2119–2128. PMID: 25099475.33. Diercks DB, Owen KP, Kontos MC, et al. Gender differences in time to presentation for myocardial infarction before and after a national women's cardiovascular awareness campaign: a temporal analysis from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress ADverse Outcomes with Early Implementation (CRUSADE) and the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network-Get with the Guidelines (NCDR ACTION Registry-GWTG). Am Heart J. 2010; 160:80–87.e3. PMID: 20598976.34. Kaul P, Armstrong PW, Sookram S, Leung BK, Brass N, Welsh RC. Temporal trends in patient and treatment delay among men and women presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:91–97. PMID: 21167339.35. Mieres JH, Gulati M, Bairey Merz N, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected ischemic heart disease: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014; 130:350–379. PMID: 25047587.36. Douglas PS, Ginsburg GS. The evaluation of chest pain in women. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1311–1315. PMID: 8609950.37. Mieres JH, Shaw LJ, Arai A, et al. Role of noninvasive testing in the clinical evaluation of women with suspected coronary artery disease: Consensus statement from the Cardiac Imaging Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005; 111:682–696. PMID: 15687114.38. Gulati M, Black HR, Shaw LJ, et al. The prognostic value of a nomogram for exercise capacity in women. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:468–475. PMID: 16079370.39. Morise AP, Lauer MS, Froelicher VF. Development and validation of a simple exercise test score for use in women with symptoms of suspected coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2002; 144:818–825. PMID: 12422150.40. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:2949–3003. PMID: 23996286.41. Huynh K. Biomarkers: high-sensitivity troponin assays for the diagnosis of AMI-sex-specific differences? Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015; 12:129. PMID: 25666408.42. Shah AS, Griffiths M, Lee KK, et al. High sensitivity cardiac troponin and the under-diagnosis of myocardial infarction in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015; 350:g7873. PMID: 25609052.43. Johnston N, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Lagerqvist B. Are we using cardiovascular medications and coronary angiography appropriately in men and women with chest pain? Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1331–1336. PMID: 21317147.44. Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, et al. The assessment of endothelial function: from research into clinical practice. Circulation. 2012; 126:753–767. PMID: 22869857.45. Knaapen P, Camici PG, Marques KM, et al. Coronary microvascular resistance: methods for its quantification in humans. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009; 104:485–498. PMID: 19468781.46. Robinson JG, Wallace R, Limacher M, et al. Cardiovascular risk in women with non-specific chest pain (from the Women's Health Initiative Hormone Trials). Am J Cardiol. 2008; 102:693–699. PMID: 18773990.47. Jespersen L, Abildstrom SZ, Hvelplund A, et al. Burden of hospital admission and repeat angiography in angina pectoris patients with and without coronary artery disease: a registry-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e93170. PMID: 24705387.48. Lempereur M, Magne J, Cornelis K, et al. Impact of gender difference in hospital outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention. Results of the Belgian Working Group on Interventional Cardiology (BWGIC) registry. EuroIntervention. 2014; 12:e216–23.49. Ahmed B, Dauerman HL. Women, bleeding, and coronary intervention. Circulation. 2013; 127:641–649. PMID: 23381962.50. Park DW, Kim YH, Yun SC, et al. Frequency, causes, predictors, and clinical significance of peri-procedural myocardial infarction following percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:1662–1669. PMID: 23404537.51. Mega JL, Hochman JS, Scirica BM, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of women with unstable ischemic heart disease: observations from metabolic efficiency with ranolazine for less ischemia in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36). Circulation. 2010; 121:1809–1817. PMID: 20385930.52. Tamis-Holland JE, Lu J, Korytkowski M, et al. Sex differences in presentation and outcome among patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease treated with contemporary medical therapy with or without prompt revascularization: a report from the BARI 2D Trial (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:1767–1776. PMID: 23500245.53. Bertrand OF, Bélisle P, Joyal D, et al. Comparison of transradial and femoral approaches for percutaneous coronary interventions: a systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2012; 163:632–648. PMID: 22520530.54. De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:1208–1217. PMID: 25176289.55. Li J, Rihal CS, Matsuo Y, et al. Sex-related differences in fractional flow reserve-guided treatment. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 6:662–670. PMID: 24149976.56. Kang SJ, Ahn JM, Han S, et al. Sex differences in the visual-functional mismatch between coronary angiography or intravascular ultrasound versus fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 6:562–568. PMID: 23787231.57. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Hocher B, et al. Gender as a risk factor in young, not in old, women undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:2413–2414. PMID: 15607409.58. Lehmkuhl E, Kendel F, Gelbrich G, et al. Gender-specific predictors of early mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Clin Res Cardiol. 2012; 101:745–751. PMID: 22527091.59. Ferreira RG, Worthington A, Huang CC, Aranki SF, Muehlschlegel JD. Sex differences in the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in cardiac surgical patients. J Card Surg. 2015; 30:238–245. PMID: 25571945.60. Kendel F, Dunkel A, Müller-Tasch T, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life after coronary bypass surgery: results from a 1-year follow-up in propensity-matched men and women. Psychosom Med. 2011; 73:280–285. PMID: 21364199.61. Kendel F, Gelbrich G, Wirtz M, et al. Predictive relationship between depression and physical functioning after coronary surgery. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170:1717–1721. PMID: 20975017.62. Kothawade K, Bairey Merz CN. Microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2011; 36:291–318. PMID: 21723447.63. Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2825–2832. PMID: 20579539.64. Murthy VL, Naya M, Taqueti VR, et al. Effects of sex on coronary microvascular dysfunction and cardiac outcomes. Circulation. 2014; 129:2518–2527. PMID: 24787469.65. Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009; 302:874–882. PMID: 19706861.66. Champney KP, Frederick PD, Bueno H, et al. The joint contribution of sex, age and type of myocardial infarction on hospital mortality following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2009; 95:895–899. PMID: 19147625.67. Otten AM, Maas AH, Ottervanger JP, et al. Is the difference in outcome between men and women treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention age dependent? Gender difference in STEMI stratified on age. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013; 2:334–341. PMID: 24338292.68. Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18:8–27.69. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:929–938. PMID: 26332547.70. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Kararigas G. Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2017; 97:1–37. PMID: 27807199.71. Arola A, Jokinen E, Ruuskanen O, et al. Epidemiology of idiopathic cardiomyopathies in children and adolescents. A nationwide study in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1997; 146:385–393. PMID: 9290498.72. Bagger JP, Baandrup U, Rasmussen K, Møller M, Vesterlund T. Cardiomyopathy in western Denmark. Br Heart J. 1984; 52:327–331. PMID: 6540593.73. Gillum RF. Idiopathic cardiomyopathy in the United States, 1970–1982. Am Heart J. 1986; 111:752–755. PMID: 3513505.74. Coughlin SS, Comstock GW, Baughman KL. Descriptive epidemiology of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in Washington County, Maryland, 1975–1991. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993; 46:1003–1008. PMID: 8263572.75. Humphries KH, Izadnegahdar M, Sedlak T, et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease - impact on care and outcomes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017; 46:46–70. PMID: 28428055.76. Ouyang P, Wenger NK, Taylor D, et al. Strategies and methods to study female-specific cardiovascular health and disease: a guide for clinical scientists. Biol Sex Differ. 2016; 7:19. PMID: 27034774.77. Clinical investigation on differences in the magnitude of CRT response in women versus men (BIOWOMEN). Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine;2015.78. Regitz-Zagrosek V, Petrov G, Lehmkuhl E, et al. Heart transplantation in women with dilated cardiomyopathy. Transplantation. 2010; 89:236–244. PMID: 20098289.79. Salama G, Bett GC. Sex differences in the mechanisms underlying long QT syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014; 307:H640–8. PMID: 24973386.80. Marijon E, Uy-Evanado A, Reinier K, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest during sports activity in middle age. Circulation. 2015; 131:1384–1391. PMID: 25847988.81. Westphal C, Spallek B, Konkel A, et al. CYP2J2 overexpression protects against arrhythmia susceptibility in cardiac hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e73490. PMID: 24023684.82. Al-Khatib SM, Hellkamp AS, Hernandez AF, et al. Trends in use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy among patients hospitalized for heart failure: have the previously observed sex and racial disparities changed over time? Circulation. 2012; 125:1094–1101. PMID: 22287589.83. MacFadden DR, Tu JV, Chong A, Austin PC, Lee DS. Evaluating sex differences in population-based utilization of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: role of cardiac conditions and noncardiac comorbidities. Heart Rhythm. 2009; 6:1289–1296. PMID: 19695966.84. Narasimha D, Curtis AB. Sex differences in utilisation and response to implantable device therapy. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2015; 4:129–135. PMID: 26835114.85. Ventura-Clapier R, Dworatzek E, Seeland U, et al. Sex in basic research: concepts in the cardiovascular field. Cardiovasc Res. 2017; 113:711–724. PMID: 28472454.86. Dworatzek E, Mahmoodzadeh S, Schriever C, et al. Sex-specific regulation of collagen I and III expression by 17β-Estradiol in cardiac fibroblasts: role of estrogen receptors. Cardiovasc Res. 2018.87. Dworatzek E, Mahmoodzadeh S, Schubert C, et al. Sex differences in exercise-induced physiological myocardial hypertrophy are modulated by oestrogen receptor beta. Cardiovasc Res. 2014; 102:418–428. PMID: 24654233.88. Fliegner D, Schubert C, Penkalla A, et al. Female sex and estrogen receptor-beta attenuate cardiac remodeling and apoptosis in pressure overload. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010; 298:R1597–606. PMID: 20375266.89. Kararigas G, Bito V, Tinel H, et al. Transcriptome characterization of estrogen-treated human myocardium identifies myosin regulatory light chain interacting protein as a sex-specific element influencing contractile function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59:410–417. PMID: 22261164.90. Kararigas G, Dworatzek E, Petrov G, et al. Sex-dependent regulation of fibrosis and inflammation in human left ventricular remodelling under pressure overload. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014; 16:1160–1167. PMID: 25287281.91. Kararigas G, Fliegner D, Forler S, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals sex and estrogen receptor β effects in the pressure overloaded heart. J Proteome Res. 2014; 13:5829–5836. PMID: 25406860.92. Kararigas G, Fliegner D, Gustafsson JA, Regitz-Zagrosek V. Role of the estrogen/estrogen-receptor-beta axis in the genomic response to pressure overload-induced hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2011; 43:438–446. PMID: 21325064.93. Kararigas G, Nguyen BT, Zelarayan LC, et al. Genetic background defines the regulation of postnatal cardiac growth by 17β-estradiol through a β-catenin mechanism. Endocrinology. 2014; 155:2667–2676. PMID: 24731099.94. Karlstädt A, Fliegner D, Kararigas G, Ruderisch HS, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Holzhütter HG. CardioNet: a human metabolic network suited for the study of cardiomyocyte metabolism. BMC Syst Biol. 2012; 6:114. PMID: 22929619.95. Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E, Fritschka S, Pham TH, Regitz-Zagrosek V. 17beta-Estradiol inhibits matrix metalloproteinase-2 transcription via MAP kinase in fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2010; 85:719–728. PMID: 19861308.96. Mahmoodzadeh S, Fritschka S, Dworatzek E, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB regulates estrogen receptor-alpha transcription in the human heart. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:24705–24714. PMID: 19584059.97. Mahmoodzadeh S, Leber J, Zhang X, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific Estrogen Receptor Alpha Increases Angiogenesis, Lymphangiogenesis and Reduces Fibrosis in the Female Mouse Heart Post-Myocardial Infarction. J Cell Sci Ther. 2014; 5:153. PMID: 24977106.98. Mahmoodzadeh S, Pham TH, Kuehne A, et al. 17β-Estradiol-induced interaction of ERα with NPPA regulates gene expression in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012; 96:411–421. PMID: 22962310.99. Schubert C, Raparelli V, Westphal C, et al. Reduction of apoptosis and preservation of mitochondrial integrity under ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by estrogen receptor β. Biol Sex Differ. 2016; 7:53. PMID: 27688871.100. Schuster I, Mahmoodzadeh S, Dworatzek E, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of oestrogen receptor β improves survival and cardiac function after myocardial infarction in female and male mice. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016; 130:365–376. PMID: 26608078.101. Queirós AM, Eschen C, Fliegner D, et al. Sex- and estrogen-dependent regulation of a miRNA network in the healthy and hypertrophied heart. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 169:331–338. PMID: 24157234.102. Li J, Ruffenach G, Kararigas G, et al. Intralipid protects the heart in late pregnancy against ischemia/reperfusion injury via Caveolin2/STAT3/GSK-3β pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017; 102:108–116. PMID: 27847332.103. Li J, Umar S, Amjedi M, et al. New frontiers in heart hypertrophy during pregnancy. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012; 2:192–207. PMID: 22937489.104. Li J, Umar S, Iorga A, et al. Cardiac vulnerability to ischemia/reperfusion injury drastically increases in late pregnancy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012; 107:271. PMID: 22648276.105. Zucker I, Beery AK. Males still dominate animal studies. Nature. 2010; 465:690. PMID: 20535186.106. Franconi F, Rosano G, Campesi I. Need for gender-specific pre-analytical testing: the dark side of the moon in laboratory testing. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 179:514–535. PMID: 25465806.107. Unsöld B, Kaul A, Sbroggiò M, et al. Melusin protects from cardiac rupture and improves functional remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2014; 101:97–107. PMID: 24130190.108. Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in pharmacology. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag;2012.109. Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Mebazaa A, et al. EURObservational Research Programme: a worldwide registry on peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) in conjunction with the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on PPCM. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014; 16:583–591. PMID: 24591060.110. Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Petrie MC, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010; 12:767–778. PMID: 20675664.111. Sliwa K, Mebazaa A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients from the worldwide registry on peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM): EURObservational Research Programme in conjunction with the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Study Group on PPCM. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017; 19:1131–1141. PMID: 28271625.112. Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52:171–180. PMID: 18617065.113. Patten IS, Rana S, Shahul S, et al. Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nature. 2012; 485:333–338. PMID: 22596155.114. Evans CS, Gooch L, Flotta D, et al. Cardiovascular system during the postpartum state in women with a history of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2011; 58:57–62. PMID: 21606389.115. Regitz-Zagrosek V. Sex and gender differences in health. Science & Society Series on Sex and Science. EMBO Rep. 2012; 13:596–603. PMID: 22699937.116. Pelletier R, Ditto B, Pilote L. A composite measure of gender and its association with risk factors in patients with premature acute coronary syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2015; 77:517–526. PMID: 25984818.117. Pelletier R, Khan NA, Cox J, et al. Sex versus gender-related characteristics: which predicts outcome after acute coronary syndrome in the young? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 67:127–135. PMID: 26791057.118. Miller VM, Kararigas G, Seeland U, et al. Integrating topics of sex and gender into medical curricula-lessons from the international community. Biol Sex Differ. 2016; 7:44. PMID: 27785346.119. Seeland U, Nauman AT, Cornelis A, et al. eGender-from e-learning to e-research: a web-based interactive knowledge-sharing platform for sex- and gender-specific medical education. Biol Sex Differ. 2016; 7:39. PMID: 27785342.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Challenges for future directions for artificial intelligence integrated nursing simulation education

- Methodological Issues in Nursing Research using IT Technology: A Discussion Paper

- Aortic Stenosis and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Current Status and Future Directions in Korea

- The Importance of Smoking Definitions for the Study of Adolescent Smoking Behavior

- Imaging Techniques for Endocrine Diseases: Current and Future Directions