Healthc Inform Res.

2018 Jul;24(3):207-226. 10.4258/hir.2018.24.3.207.

Effectiveness of Mobile Health Application Use to Improve Health Behavior Changes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Nursing, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- 2College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea. jewelee@knu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2418171

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2018.24.3.207

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of mobile health applications in changing health-related behaviors and clinical health outcomes.

METHODS

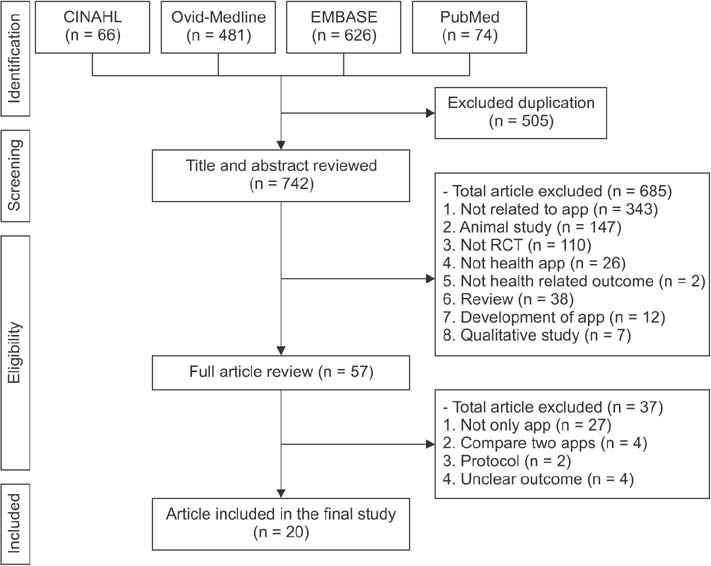

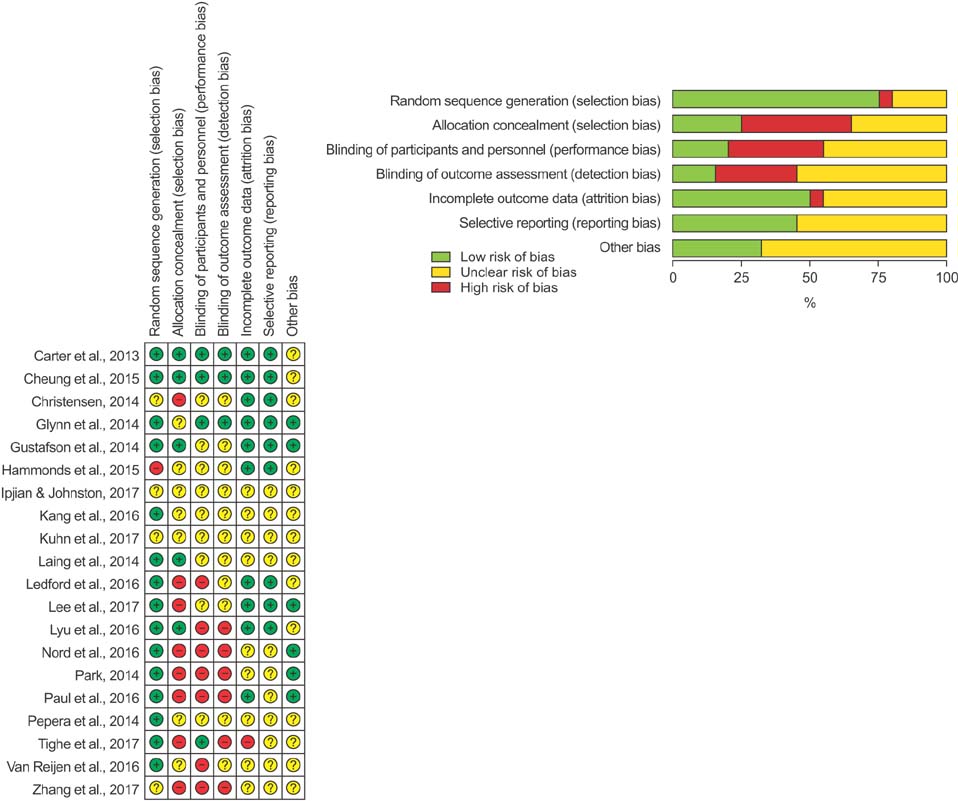

A systematic review was conducted in this study. We conducted a comprehensive bibliographic search of articles on health behavior changes related to the use of mobile health applications in peer-reviewed journals published between January 1, 2000 and May 31, 2017. We used databases including CHINAHL, Ovid-Medline, EMBASE, and PubMed. The risk of bias assessment of the retrieved articles was examined using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

RESULTS

A total of 20 articles met the inclusion criteria. Sixteen among 20 studies reported that applications have a positive impact on the targeted health behaviors or clinical health outcomes. In addition, most of the studies, which examined the satisfaction of participants, showed health app users have a statistically significant higher satisfaction.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the high risk of bias, such as selection, performance, and detection, this systematic review found that the use of mobile health applications has a positive impact on health-related behaviors and clinical health outcomes. Application users were more satisfied with using mobile health applications to manage their health in comparison to users of conventional care.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Need Assessment for Smartphone-Based Cardiac Telerehabilitation

Ji-Su Kim, Doeun Yun, Hyun Joo Kim, Ho-Youl Ryu, Jaewon Oh, Seok-Min Kang

Healthc Inform Res. 2018;24(4):283-291. doi: 10.4258/hir.2018.24.4.283.Design and Validation of a Computer Application for Diagnosis of Shoulder Locomotor System Pathology

Albert Bigorda-Sague, Javier Trujillano Cabello, Gemma Ariza Carrio, Carmen Campoy Guerrero

Healthc Inform Res. 2019;25(2):82-88. doi: 10.4258/hir.2019.25.2.82.

Reference

-

1. Lee J, Lee M, Lim T, Kim T, Kim S, Suh D, et al. Effectiveness of an application-based neck exercise as a pain management tool for office workers with chronic neck pain and functional disability: a pilot randomized trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2017; 12:87–92.

Article2. Boudreaux ED, Waring ME, Hayes RB, Sadasivam RS, Mullen S, Pagoto S. Evaluating and selecting mobile health apps: strategies for healthcare providers and healthcare organizations. Transl Behav Med. 2014; 4(4):363–371.

Article3. Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. Can mobile phone apps influence people's health behavior change? An evidence review. J Med Internet Res. 2016; 18(11):e287.

Article4. Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, Galli L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013; 10(1):e1001363.

Article5. Kitsiou S, Pare G, Jaana M, Gerber B. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for patients with diabetes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2017; 12(3):e0173160.

Article6. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015; 4:1.

Article7. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [Internet]. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Healthcare Improvement Scotland;c2018. cited at 2018 Jul 1. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/.8. Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, et al. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71(5):566–572.

Article9. Van Reijen M, Vriend I, Zuidema V, van Mechelen W, Verhagen EA. The “Strengthen your ankle” program to prevent recurrent injuries: a randomized controlled trial aimed at long-term effectiveness. J Sci Med Sport. 2017; 20(6):549–554.

Article10. Laing BY, Mangione CM, Tseng CH, Leng M, Vaisberg E, Mahida M, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161:10 Suppl. S5–S12.11. Nord A, Svensson L, Hult H, Kreitz-Sandberg S, Nilsson L. Effect of mobile application-based versus DVD-based CPR training on students' practical CPR skills and willingness to act: a cluster randomised study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6(4):e010717.

Article12. Kang X, Zhao L, Leung F, Luo H, Wang L, Wu J, et al. Delivery of instructions via mobile social media app increases quality of bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 14(3):429–435.e3.

Article13. Kuhn E, Kanuri N, Hoffman JE, Garvert DW, Ruzek JI, Taylor CB. A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone app for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017; 85(3):267–273.

Article14. Ledford CJW, Canzona MR, Cafferty LA, Hodge JA. Mobile application as a prenatal education and engagement tool: a randomized controlled pilot. Patient Educ Couns. 2016; 99(4):578–582.

Article15. Hammonds T, Rickert K, Goldstein C, Gathright E, Gilmore S, Derflinger B, et al. Adherence to antidepressant medications: a randomized controlled trial of medication reminding in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2015; 63(3):204–208.

Article16. Carter MC, Burley VJ, Nykjaer C, Cade JE. Adherence to a smartphone application for weight loss compared to website and paper diary: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 15(4):e32.

Article17. Cheung YT, Chan CH, Lai CK, Chan WF, Wang MP, Li HC, et al. Using WhatsApp and Facebook online social groups for smoking relapse prevention for recent quitters: a pilot pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17(10):e238.

Article18. Lyu KX, Zhao J, Wang B, Xiong GX, Yang WQ, Liu QH, et al. Smartphone application WeChat for clinical follow-up of discharged patients with head and neck tumors: a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016; 129(23):2816–2823.

Article19. Glynn LG, Hayes PS, Casey M, Glynn F, Alvarez-Iglesias A, Newell J, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application to promote physical activity in primary care: the SMART MOVE randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2014; 64(624):e384–e391.

Article20. Tighe J, Shand F, Ridani R, Mackinnon A, De La Mata N, Christensen H. Ibobbly mobile health intervention for suicide prevention in Australian Indigenous youth: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(1):e013518.

Article21. Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008; 27(3):379–387.

Article22. Sullivan GM. Getting off the “gold standard”: randomized controlled trials and education research. J Grad Med Educ. 2011; 3(3):285–289.

Article23. Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O'Rourke K, Molnar FJ, Mahon J, Chan KB, et al. Determination of the clinical importance of study results. J Gen Intern Med. 2002; 17(6):469–476.

Article24. Linke SE, Gallo LC, Norman GJ. Attrition and adherence rates of sustained vs. intermittent exercise interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2011; 42(2):197–209.

Article25. Ipjian ML, Johnston CS. Smartphone technology facilitates dietary change in healthy adults. Nutrition. 2017; 33:343–347.

Article26. Paul L, Wyke S, Brewster S, Sattar N, Gill JM, Alexander G, et al. Increasing physical activity in stroke survivors using STARFISH, an interactive mobile phone application: a pilot study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2016; 23(3):170–177.

Article27. Park SS. Comparison of chest compression quality between the modified chest compression method with the use of smartphone application and the standardized traditional chest compression method during CPR. Technol Health Care. 2014; 22(3):351–358.

Article28. Perera AI, Thomas MG, Moore JO, Faasse K, Petrie KJ. Effect of a smartphone application incorporating personalized health-related imagery on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014; 28(11):579–586.

Article29. Zhang H, Jiang Y, Nguyen HD, Poo DC, Wang W. The effect of a smartphone-based coronary heart disease prevention (SBCHDP) programme on awareness and knowledge of CHD, stress, and cardiac-related lifestyle behaviours among the working population in Singapore: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017; 15(1):49.

Article30. Christensen S. Evaluation of a nurse-designed mobile health education application to enhance knowledge of Pap testing. Creat Nurs. 2014; 20(2):137–143.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Website and Mobile Application-Based Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults with Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Maternal Health Effects of Internet-Based Education Interventions during the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review

- Interventions for Dysphagia following Stroke: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

- Effects of a Health Partnership Program Using Mobile Health Application for Male Workers with Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Small and Medium Enterprises: A Randomized Controlled Trial

- Effects of Using Mobile Apps for Mental Health Care in Korea: A Systematic Review