J Clin Neurol.

2018 Jul;14(3):374-380. 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.3.374.

The Etiologies of Chronic Progressive Cerebellar Ataxia in a Korean Population

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. jinwhan.cho@samsung.com

- 2Neuroscience Center, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine and Genetics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2415055

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2018.14.3.374

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

The etiologies and frequencies of cerebellar ataxias vary between countries. Our primary aim was to determine the frequency of each diagnostic group of cerebellar ataxia patients in a Korean population.

METHODS

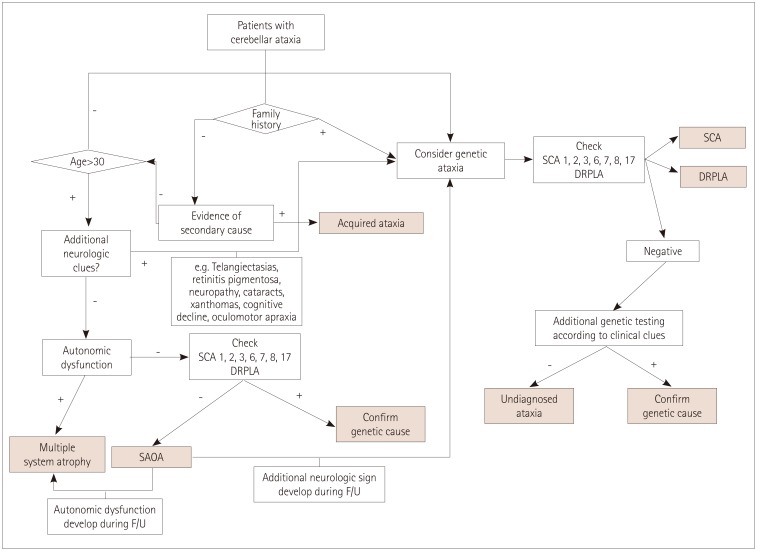

We reviewed the medical records of patients who were being followed up between November 1994 and February 2016. We divided patients with cerebellar ataxias into familial and non-familial groups and analyzed the frequency of each etiology. Finally, we categorized patients into genetic, sporadic, secondary, and suspected genetic, but undetermined ataxia.

RESULTS

A total of 820 patients were included in the study, among whom 136 (16.6%) familial patients and 684 (83.4%) non-familial cases were identified. Genetic diagnoses confirmed 98/136 (72%) familial and 72/684 (11%) nonfamilial patients. The overall etiologies of progressive ataxias comprised 170 (20.7%) genetic, 516 (62.9%) sporadic, 43 (5.2%) secondary, and 91 (11.1%) undetermined ataxia. The most common cause of ataxia was multiple-system atrophy (57.3%). In the genetic group, the most common etiology was spinocerebellar ataxia (152/170, 89.4%) and the most common subtype was spinocerebellar ataxia-3.38 of 136 familial and 53 of 684 sporadic cases (91/820, 11.1%) were undetermined ataxia.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the largest epidemiological study to analyze the frequencies of various cerebellar ataxias in a Korean population based on the large database of a tertiary hospital movement-disorders clinic in South Korea. These data would be helpful for clinicians in constructing diagnostic strategies and counseling for patients with cerebellar ataxias.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

The Rise of Cerebellar Ataxia in South Korea: 2002–2016

YoonAh Park, Kun-Woo Park

J Clin Neurol. 2020;16(1):175-176. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2020.16.1.175.Detection Methods and Status of CAT Interruption of

ATXN1 in Korean Patients With Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1

Ja-Hyun Jang, Sun Joo Yoon, Sun-Kyung Kim, Jin Whan Cho, Jong-Won Kim

Ann Lab Med. 2022;42(2):274-277. doi: 10.3343/alm.2022.42.2.274.

Reference

-

1. Brusse E, Maat-Kievit JA, van Swieten JC. Diagnosis and management of early- and late-onset cerebellar ataxia. Clin Genet. 2007; 71:12–24. PMID: 17204042.

Article2. Fogel BL, Perlman S. Clinical features and molecular genetics of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias. Lancet Neurol. 2007; 6:245–257. PMID: 17303531.

Article3. Klockgether T. Sporadic ataxia with adult onset: classification and diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2010; 9:94–104. PMID: 20083040.

Article4. Fogel BL, Perlman S. An approach to the patient with late-onset cerebellar ataxia. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006; 2:629–635. PMID: 17057750.

Article5. Kim JS, Cho JW. Hereditary cerebellar ataxias: a Korean perspective. J Mov Disord. 2015; 8:67–75. PMID: 26090078.

Article6. Gebus O, Montaut S, Monga B, Wirth T, Cheraud C, Alves Do Rego C, et al. Deciphering the causes of sporadic late-onset cerebellar ataxias: a prospective study with implications for diagnostic work. J Neurol. 2017; 264:1118–1126. PMID: 28478596.

Article7. Hadjivassiliou M, Martindale J, Shanmugarajah P, Grünewald RA, Sarrigiannis PG, Beauchamp N, et al. Causes of progressive cerebellar ataxia: prospective evaluation of 1500 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017; 88:301–309. PMID: 27965395.

Article8. Basu P, Chattopadhyay B, Gangopadhaya PK, Mukherjee SC, Sinha KK, Das SK, et al. Analysis of CAG repeats in SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7 and DRPLA loci in spinocerebellar ataxia patients and distribution of CAG repeats at the SCA1, SCA2 and SCA6 loci in nine ethnic populations of eastern India. Hum Genet. 2000; 106:597–604. PMID: 10942107.

Article9. Maruyama H, Izumi Y, Morino H, Oda M, Toji H, Nakamura S, et al. Difference in disease-free survival curve and regional distribution according to subtype of spinocerebellar ataxia: a study of 1,286 Japanese patients. Am J Med Genet. 2002; 114:578–583. PMID: 12116198.

Article10. Nagaoka U, Suzuki Y, Kawanami T, Kurita K, Shikama Y, Hondad K, et al. Regional differences in genetic subgroup frequency in hereditary cerebellar ataxia, and a morphometrical study of brain MR images in SCA1, MJD and SCA6. J Neurol Sci. 1999; 164:187–194. PMID: 10402032.

Article11. Pujana MA, Corral J, Gratacòs M, Combarros O, Berciano J, Genís D, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Spanish patients: genetic analysis of familial and sporadic cases. The Ataxia Study Group. Hum Genet. 1999; 104:516–522. PMID: 10453742.12. Ranum LP, Lundgren JK, Schut LJ, Ahrens MJ, Perlman S, Aita J, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 and Machado-Joseph disease: incidence of CAG expansions among adult-onset ataxia patients from 311 families with dominant, recessive, or sporadic ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1995; 57:603–608. PMID: 7668288.13. Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, Brooks DJ, Mathias CJ, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008; 71:670–676. PMID: 18725592.

Article14. Abele M, Bürk K, Schöls L, Schwartz S, Besenthal I, Dichgans J, et al. The aetiology of sporadic adult-onset ataxia. Brain. 2002; 125:961–968. PMID: 11960886.

Article15. Klockgether T, Lüdtke R, Kramer B, Abele M, Bürk K, Schöls L, et al. The natural history of degenerative ataxia: a retrospective study in 466 patients. Brain. 1998; 121:589–600. PMID: 9577387.

Article16. Jamora RD, Gupta A, Tan AK, Tan LC. Clinical characteristics of patients with multiple system atrophy in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005; 34:553–557. PMID: 16284677.17. Ota S, Tsuchiya K, Anno M, Niizato K, Akiyama H. Distribution of cerebello-olivary degeneration in idiopathic late cortical cerebellar atrophy: clinicopathological study of four autopsy cases. Neuropathology. 2008; 28:43–50. PMID: 18181834.

Article18. Muzaimi MB, Thomas J, Palmer-Smith S, Rosser L, Harper PS, Wiles CM, et al. Population based study of late onset cerebellar ataxia in south east Wales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004; 75:1129–1134. PMID: 15258214.

Article19. Schöls L, Bauer P, Schmidt T, Schulte T, Riess O. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004; 3:291–304. PMID: 15099544.

Article20. Silveira I, Miranda C, Guimarães L, Moreira MC, Alonso I, Mendonça P, et al. Trinucleotide repeats in 202 families with ataxia: a small expanded (CAG)n allele at the SCA17 locus. Arch Neurol. 2002; 59:623–629. PMID: 11939898.21. Tang B, Liu C, Shen L, Dai H, Pan Q, Jing L, et al. Frequency of SCA1, SCA2, SCA3/MJD, SCA6, SCA7, and DRPLA CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion in patients with hereditary spinocerebellar ataxia from Chinese kindreds. Arch Neurol. 2000; 57:540–544. PMID: 10768629.

Article22. Jin DK, Oh MR, Song SM, Koh SW, Lee M, Kim GM, et al. Frequency of spinocerebellar ataxia types 1,2,3,6,7 and dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy mutations in Korean patients with spinocerebellar ataxia. J Neurol. 1999; 246:207–210. PMID: 10323319.23. Lee WY, Jin DK, Oh MR, Lee JE, Song SM, Lee EA, et al. Frequency analysis and clinical characterization of spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 in Korean patients. Arch Neurol. 2003; 60:858–863. PMID: 12810491.

Article24. Kim HJ, Jeon BS, Lee WY, Chung SJ, Yong SW, Kang JH, et al. SCA in Korea and its regional distribution: a multicenter analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011; 17:72–75. PMID: 20951073.

Article25. Kim JY, Park SS, Joo SI, Kim JM, Jeon BS. Molecular analysis of spinocerebellar ataxias in Koreans: frequencies and reference ranges of SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, and SCA7. Mol Cells. 2001; 12:336–341. PMID: 11804332.26. Huh HJ, Cho KH, Lee JE, Kwon MJ, Ki CS, Lee PH. Identification of ATM mutations in Korean siblings with ataxia-telangiectasia. Ann Lab Med. 2013; 33:217–220. PMID: 23667852.

Article27. Schöls L, Szymanski S, Peters S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Hardt C, et al. Genetic background of apparently idiopathic sporadic cerebellar ataxia. Hum Genet. 2000; 107:132–137. PMID: 11030410.

Article28. Shizuka M, Watanabe M, Ikeda Y, Mizushima K, Okamoto K, Shoji M. Molecular analysis of a de novo mutation for spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 and (CAG)n repeat units in normal elder controls. J Neurol Sci. 1998; 161:85–87. PMID: 9879686.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Progressive Ataxia and Palatal Tremor

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy with Predominant Cerebellar Ataxia

- Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8 Presenting as Ataxia without Definite Cerebellar Atrophy

- A case of ataxia telangiectasia

- Early Onset Cerebellar Ataxia with Retained Tendon Reflexes Developed in Brothers: Report of two cases