Korean Circ J.

2018 Jun;48(6):492-504. 10.4070/kcj.2017.0128.

Risk Scoring System to Assess Outcomes in Patients Treated with Contemporary Guideline-Adherent Optimal Therapies after Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Heart Stroke Vascular Center, Mediplex Sejong General Hospital, Incheon, Korea.

- 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 3Division of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Center, Mediplex Sejong Hospital, Incheon, Korea.

- 4Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. sh1214.choi@samsung.com

- 5Heart Research Center, Chonnam National University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea.

- KMID: 2412541

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2017.0128

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

A risk prediction is needed even in the contemporary era of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). We sought to develop a risk scoring specific for patients with AMI being treated with guideline-adherent optimal therapies, including percutaneous coronary intervention and all 5 medications (aspirin, thienopyridine, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and statin).

METHODS

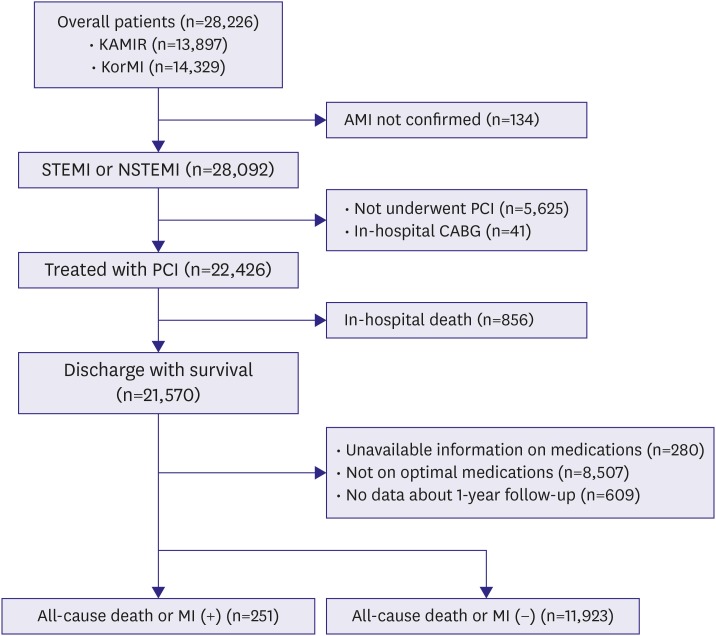

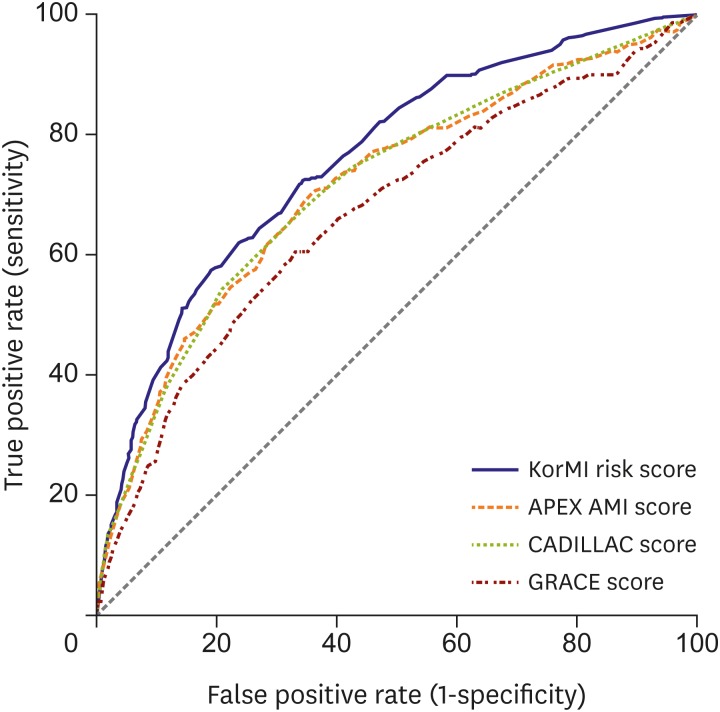

From registries, 12,174 AMI patients were evaluated. The primary outcome was 1-year all-cause death or AMI. The Korea Working Group in Myocardial Infarction (KorMI) system was compared with the Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction (APEX AMI), Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC), and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events scores (GRACE) models.

RESULTS

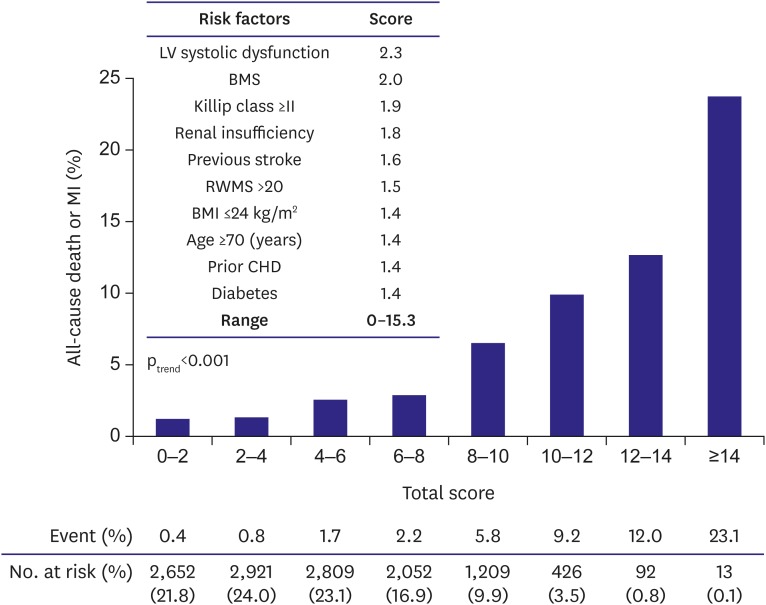

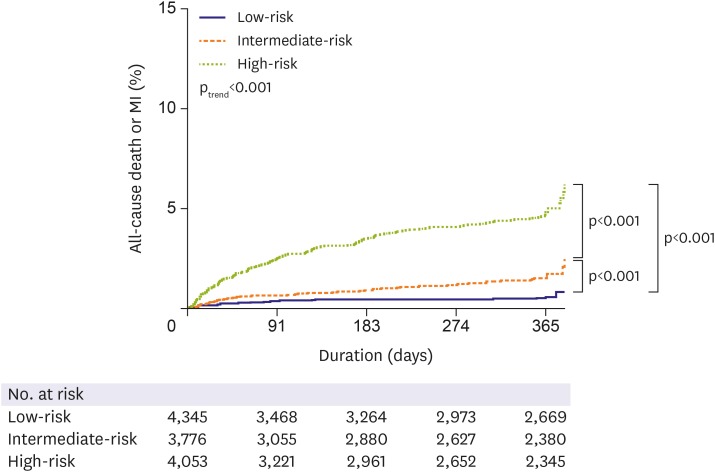

Ten predictors were identified: left ventricular dysfunction (hazard ratio [HR], 2.3), bare-metal stent (HR, 2.0), Killip class ≥II (HR, 1.9), renal insufficiency (HR, 1.8), previous stroke (HR, 1.6), regional wall-motion- score >20 on echocardiography (HR, 1.5), body mass index ≤24 kg/m2 (HR, 1.4), age ≥70 years (HR, 1.4), prior coronary heart disease (HR, 1.4), and diabetes (HR, 1.4). Compared with the previous models, the KorMI system had good discrimination (time-dependent C statistic, 0.759) and showed reasonable goodness-of-fit by Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p=0.84). Moreover, the continuous-net reclassification improvement varied from −27.3% to −19.1%, the integrated discrimination index varied from −2.1% to −0.9%, and the median improvement in risk score was from −1.0% to −0.4%.

CONCLUSIONS

The KorMI system would be a useful tool for predicting outcomes in survivors treated with guideline-adherent optimal therapies after AMI.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

A New Prognostic Tool for Korean Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction

Hyeon Chang Kim

Korean Circ J. 2018;48(6):505-506. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2018.0127.

Reference

-

1. Kim HK, Jeong MH, Lee SH, et al. The scientific achievements of the decades in Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. Korean J Intern Med. 2014; 29:703–712. PMID: 25378967.2. Pilgrim T, Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, et al. Risk and timing of recurrent ischemic events among patients with stable ischemic heart disease, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2016; 175:56–65. PMID: 27179724.3. Arnold SV, Smolderen KG, Kennedy KF, et al. Risk factors for rehospitalization for acute coronary syndromes and unplanned revascularization following acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015; 4:e001352. PMID: 25666368.4. Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000; 284:835–842. PMID: 10938172.5. Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, et al. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004; 291:2727–2733. PMID: 15187054.6. Bawamia B, Mehran R, Qiu W, Kunadian V. Risk scores in acute coronary syndrome and percutaneous coronary intervention: a review. Am Heart J. 2013; 165:441–450. PMID: 23537960.7. Stebbins A, Mehta RH, Armstrong PW, et al. A model for predicting mortality in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:414–422. PMID: 20858863.8. Halkin A, Singh M, Nikolsky E, et al. Prediction of mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: the CADILLAC risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1397–1405. PMID: 15862409.9. Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007; 115:928–935. PMID: 17309939.10. Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med. 1997; 16:965–980. PMID: 9160492.11. Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008; 27:157–172. PMID: 17569110.12. Cannon CP, Brindis RG, Chaitman BR, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Acute Coronary Syndromes and Coronary Artery Disease Clinical Data Standards). Circulation. 2013; 127:1052–1089. PMID: 23357718.13. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976; 16:31–41. PMID: 1244564.14. Blanche P, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Estimating and comparing time-dependent areas under receiver operating characteristic curves for censored event times with competing risks. Stat Med. 2013; 32:5381–5397. PMID: 24027076.15. Uno H, Tian L, Cai T, Kohane IS, Wei LJ. A unified inference procedure for a class of measures to assess improvement in risk prediction systems with survival data. Stat Med. 2013; 32:2430–2442. PMID: 23037800.16. Kueh SH, Devlin G, Lee M, Doughty RN, Kerr AJ. Management and long-term outcome of acute coronary syndrome patients presenting with heart failure in a contemporary New Zealand cohort (ANZACS-QI 4). Heart Lung Circ. 2016; 25:837–846. PMID: 27132622.17. Møller JE, Hillis GS, Oh JK, Reeder GS, Gersh BJ, Pellikka PA. Wall motion score index and ejection fraction for risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006; 151:419–425. PMID: 16442909.18. Bangalore S, Amoroso N, Fusaro M, Kumar S, Feit F. Outcomes with various drug-eluting or bare metal stents in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a mixed treatment comparison analysis of trial level data from 34 068 patient-years of follow-up from randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 6:378–390. PMID: 23922145.19. Khot UN, Jia G, Moliterno DJ, et al. Prognostic importance of physical examination for heart failure in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: the enduring value of Killip classification. JAMA. 2003; 290:2174–2181. PMID: 14570953.20. Loncar G, Barthelemy O, Berman E, et al. Impact of renal failure on all-cause mortality and other outcomes in patients treated by percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015; 108:554–562. PMID: 26184868.21. Subherwal S, Bhatt DL, Li S, et al. Polyvascular disease and long-term cardiovascular outcomes in older patients with non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012; 5:541–549. PMID: 22715460.22. Park KH, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, et al. Different impact of diabetes mellitus on in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. Korean J Intern Med. 2012; 27:180–188. PMID: 22707890.23. Kaltoft A, Kelbaek H, Thuesen L, et al. Long-term outcome after drug-eluting versus bare-metal stent implantation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 3-year follow-up of the randomized DEDICATION (Drug Elution and Distal Protection in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:641–645. PMID: 20688033.24. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1045–1057. PMID: 19717846.25. DeFilippis AP, Young R, Carrubba CJ, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162:266–275. PMID: 25686167.26. Steyerberg EW, Vergouwe Y. Towards better clinical prediction models: seven steps for development and an ABCD for validation. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35:1925–1931. PMID: 24898551.27. Roecker EB. Prediction error and its estimation for subset-selected models. Technometrics. 1991; 33:459–468.28. Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007; 297:177–186. PMID: 17213401.29. Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, et al. Beyond medication prescription as performance measures: optimal secondary prevention medication dosing after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:1791–1801. PMID: 23973701.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Significance of QRS Scoring System in the Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Invasive Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction: What is the Optimal Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction?

- Effect of Angina Pectoris before Acute Myocardial Infarction on Degree of Residual Stenosis after Successful Coronary Thrombolysis

- Risk Stratification of Acute Coronary Syndrome

- Clinical Study of Risk Factors in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction