J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2018 May;59(5):397-402. 10.3341/jkos.2018.59.5.397.

Treatment of Periorbital Infantile Capillary Hemangioma with Propranolol

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea. oculoplasty@gmail.com

- 2T2B Infrastructure Center for Ocular Disease, Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- KMID: 2411447

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2018.59.5.397

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report the clinical results of systemic propranolol for infantile periorbital hemangiomas.

METHODS

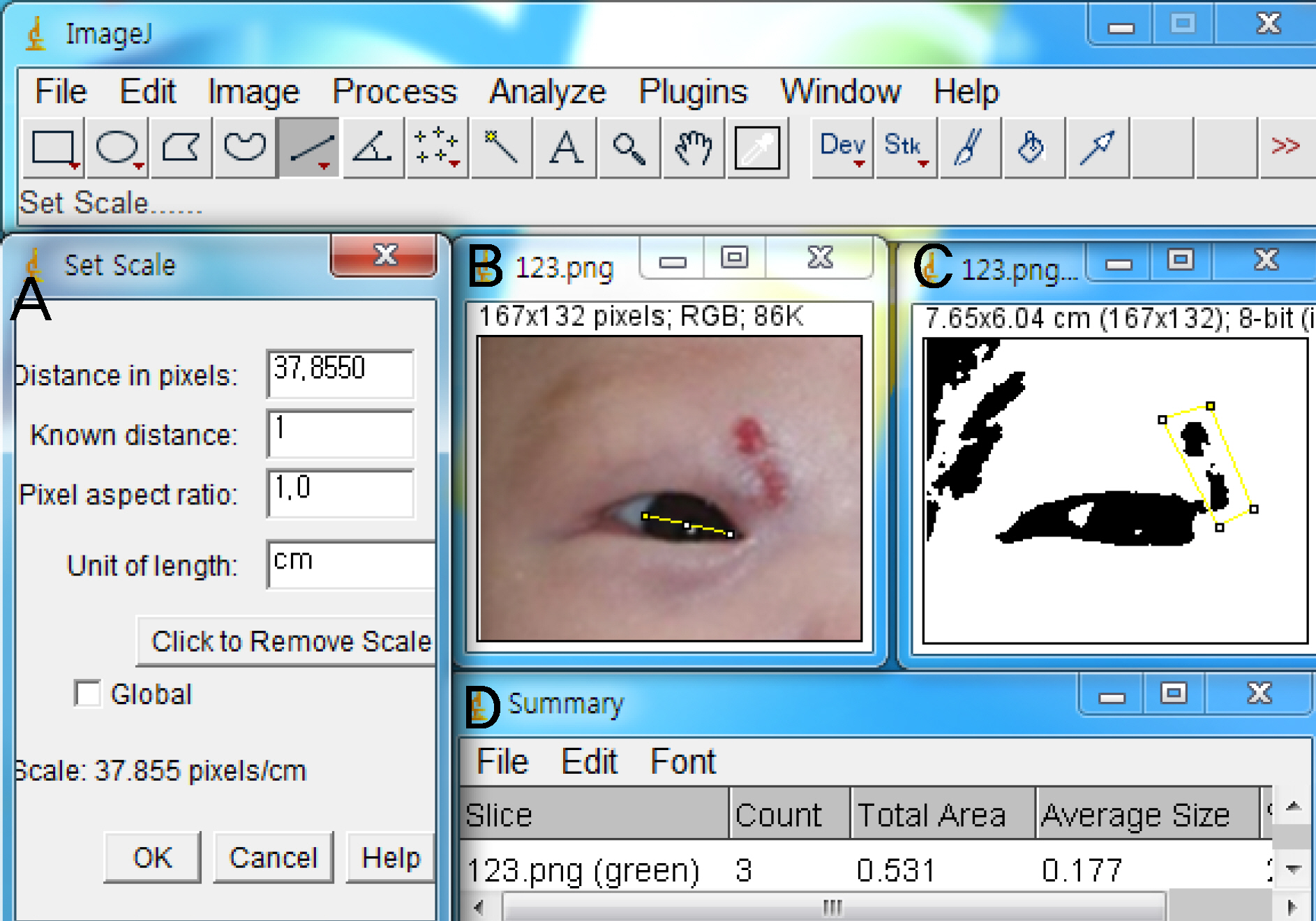

A retrospective analysis was performed on 11 patients who were treated with beta-blockers for cosmetic purposes or for those with an invalid visual axis from January 2010 to June 2017. A beta receptor blocker (propranolol) was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day. The size of the lesion was analyzed using Image J software, version 1.47 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) at 1-2 months until the drug was discontinued after the initial treatment and discharge. We observed the occurrence of side effects such as hypoglycemia, nausea, and vomiting due to drug use.

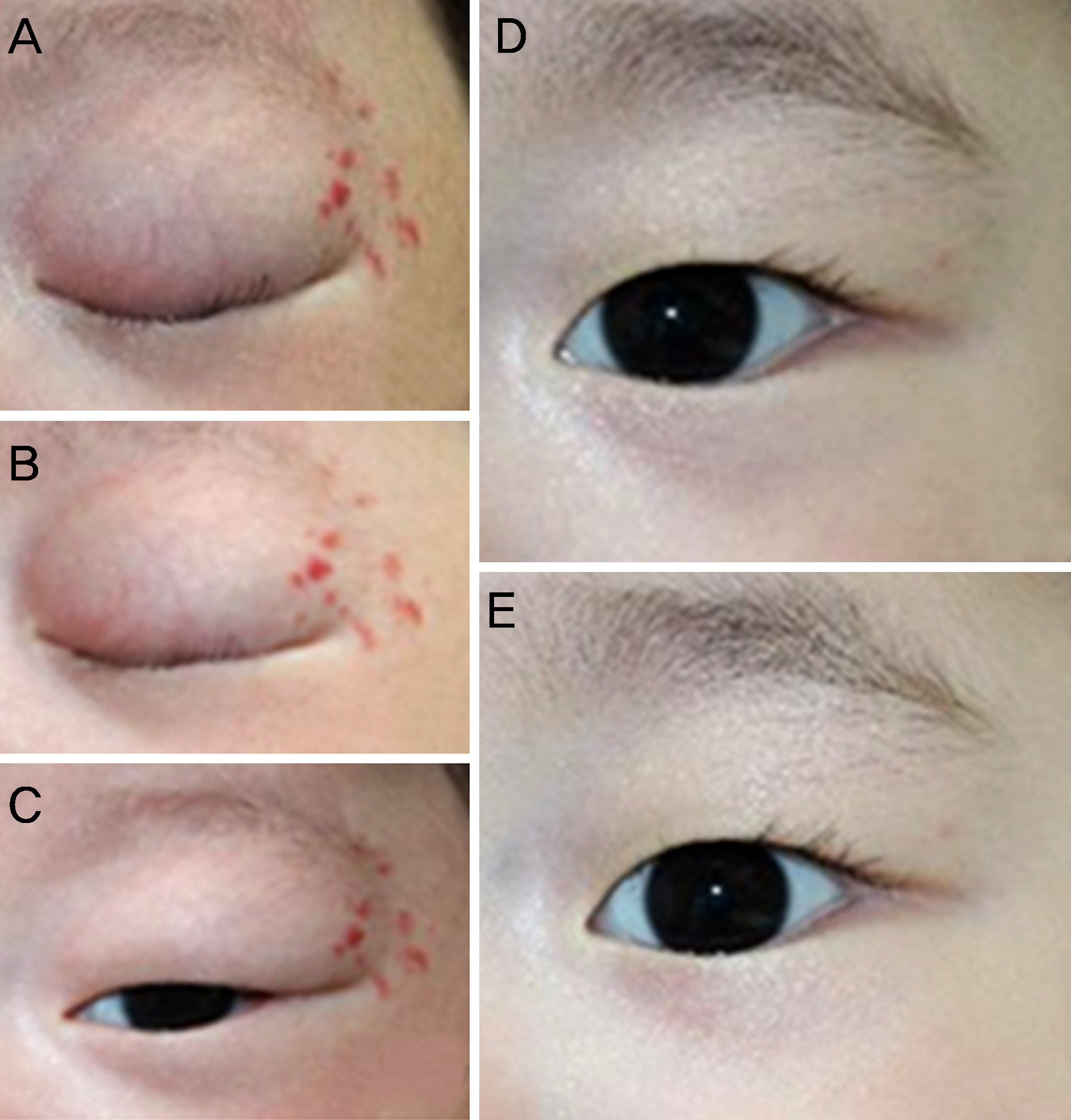

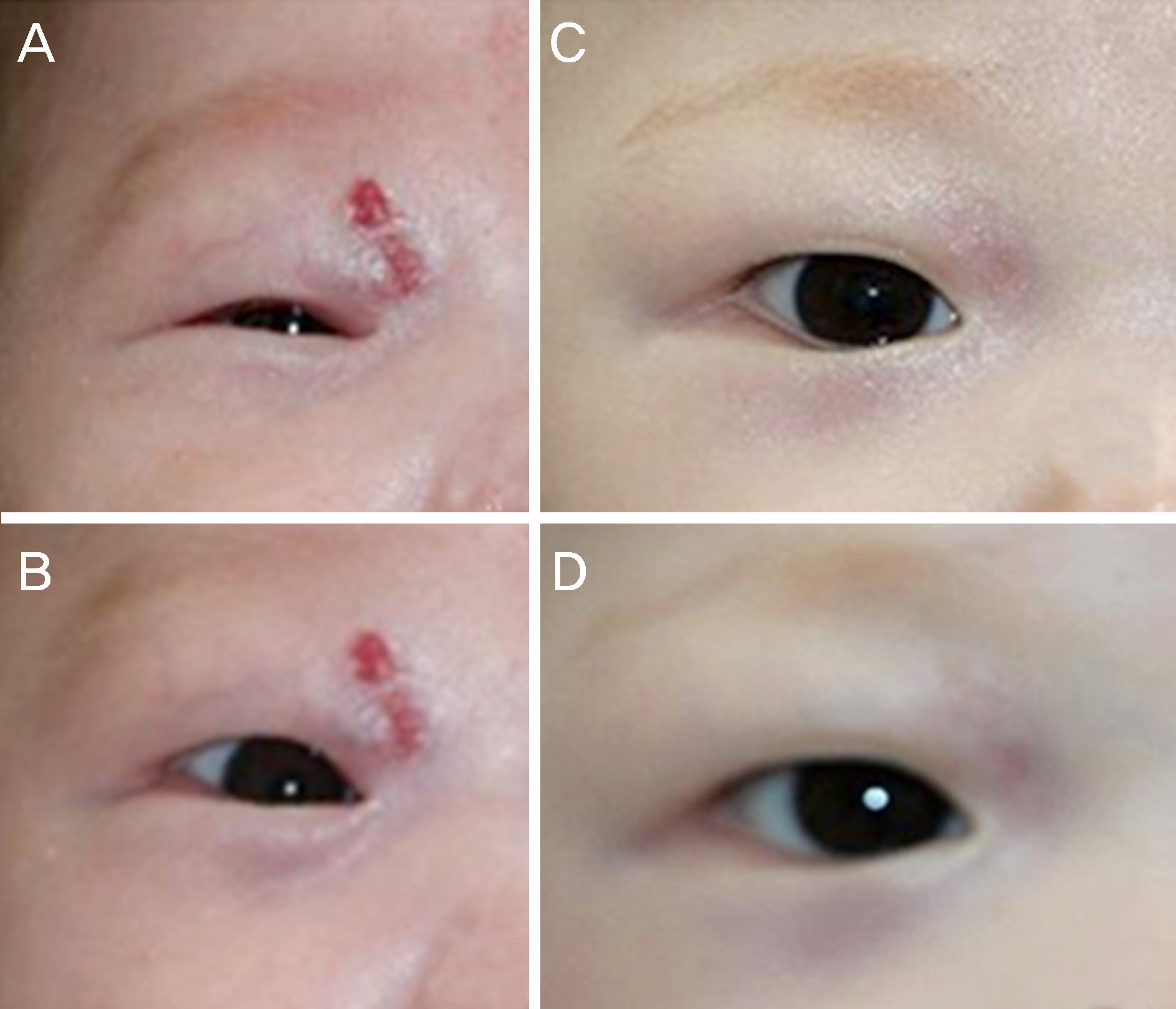

RESULTS

Of the 11 patients, 9 (82%) were female and 2 (18%) were male. The location of the capillary hemangioma was in the upper eyelid of eight eyes (72.7%) and in the lower eyelid of three eyes (27.3%). The mean duration of treatment was 6.2 months and the mean follow-up period was 8.3 months. In 11 patients (100%), the lesion size was reduced. A temporary allergic response was seen in one patient, but no adverse side effects were seen that involved life-threatening effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Infantile hemangiomas may cause cosmetic problems and amblyopia when invading the visual axis, which may require active treatment. Oral beta-blocker therapy for infantile hemangiomas of the orbit was safe for months or longer, with adequate treatment and with little to no adverse effects.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth abdominal of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008; 122:360–7.2. Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. The current management of vascular birthmarks. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993; 10:311–3.

Article3. Margileth AM, Museles M. Cutaneous hemangiomas in children. Diagnosis and conservative management. JAMA. 1965; 194:523–6.

Article4. Ceisler E, Blei F. Ophthalmic issues in hemangiomas of infancy. Lymphat Res Biol. 2003; 1:321–30.

Article5. Frieden IJ, Eichenfield LF, Esterly NB, et al. Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy. American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:631–7.6. Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:2649–51.

Article7. Jian D, Chen X, Babajee K, et al. Adverse effects of propranolol treatment for infantile hemangiomas in China. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014; 25:388–90.

Article8. Lawley LP, Siegfried E, Todd JL. Propranolol treatment for abdominal of infancy: risks and recommendations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009; 26:610–4.9. Holmdahl K. Cutaneous hemangiomas in premature and mature infants. Acta Paediatr. 1955; 44:370–9.

Article10. Haik BG, Karcioglu ZA, Gordon RA, Pechous BP. Capillary abdominal (infantile periocular hemangioma). Surv Ophthalmol. 1994; 38:399–426.11. Stigmar G, Crawford JS, Ward CM, Thomson HG. Ophthalmic abdominal of infantile hemangiomas of the eyelids and orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978; 85:806–13.12. Bruckner AL, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48:477–93. quiz 494–6.

Article13. Chen TS, Eichenfield LF, Friedlander SF. Infantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Pediatrics. 2013; 131:99–108.

Article14. Maguiness SM, Frieden IJ. Current management of infantile hemangiomas. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010; 29:106–14.

Article15. Michaud AP, Bauman NM, Burke DK, et al. Spastic diplegia and other motor disturbances in infants receiving interferon-alpha. Laryngoscope. 2004; 114:1231–6.

Article16. Zaher H, Rasheed H, Hegazy RA, et al. Oral propranolol: an abdominal, safe treatment for infantile hemangiomas. Eur J Dermatol. 2011; 21:558–63.17. Sans V, de la Roque ED, Berge J, et al. Propranolol for severe abdominal hemangiomas: follow-up report. Pediatrics. 2009; 124:e423–31.18. Schupp CJ, Kleber JB, Günther P, Holland-Cunz S. Propranolol therapy in 55 infants with infantile hemangioma: dosage, duration, adverse effects, and outcome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011; 28:640–4.

Article19. Chinnadurai S, Fonnesbeck C, Snyder KM, et al. Pharmacologic interventions for infantile hemangioma: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016; 137:e20153896.

Article20. de Graaf M, Breur JM, Raphaël MF, et al. Adverse effects of abdominal when used in the treatment of hemangiomas: a case series of 28 infants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65:320–7.21. Kwon EK, Joachim S, Siegel DH, et al. Retrospective review of abdominal effects from propranolol in infants. JAMA Dermatol. 2013; 149:484–5.22. Giachetti A, Garcia‑ Monaco R, Sojo M, et al. Long‑ term treatment with oral propranolol reduces relapses of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014; 31:14–20.23. Pope E, Krafchik BR, Macarthur C, et al. Oral versus high-dose pulse corticosteroids for problematic infantile hemangiomas: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2007; 119:e1239–47.

Article24. Al Dhaybi R, Superstein R, Milet A, et al. Treatment of periocular infantile hemangiomas with propranolol: case series of 18 children. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1184–8.

Article25. Vassallo P, Forte R, Di Mezza A, Magli A. Treatment of infantile capillary hemangioma of the eyelid with systemic propranolol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013; 155:165–70.e2.

Article26. Lee EK, Choung HK, Kim NJ, et al. A case of periorbital infantile capillary hemangioma treated with propranolol. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010; 51:1513–19.

Article27. Song NH, Kim DH. A case of periocular capillary hemangiomas treated with propranolol as a single therapy. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2012; 53:607–11.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Periocular Capillary Hemangiomas Treated With Propranolol as a Single Therapy

- A Case of Periorbital Infantile Capillary Hemangioma Treated With Propranolol

- Ulcerated Perianal Infantile Hemangioma Treated with Propranolol

- Giant Infantile Hemangioma Treated with Beta-blocker with Intermittent Triamcinolone Intralesional Injection

- Three Cases of Infantile Hemanioma Treated with Topical Timolol