J Educ Eval Health Prof.

2017;14:24. 10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.24.

Does the acceptance of hybrid learning affect learning approaches in France?

- Affiliations

-

- 1TIMC-IMAG UMR 5525, Themas, CNRS, Grenoble-Alpes University, Grenoble, France. dimarcol@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

- 2Midwifery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Grenoble-Alpes University, Grenoble, France.

- 3LIMICS, UMRS 1142 & Paris 13 University & UPMC Paris 6 University, Paris, France.

- KMID: 2406687

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.24

Abstract

- PURPOSE

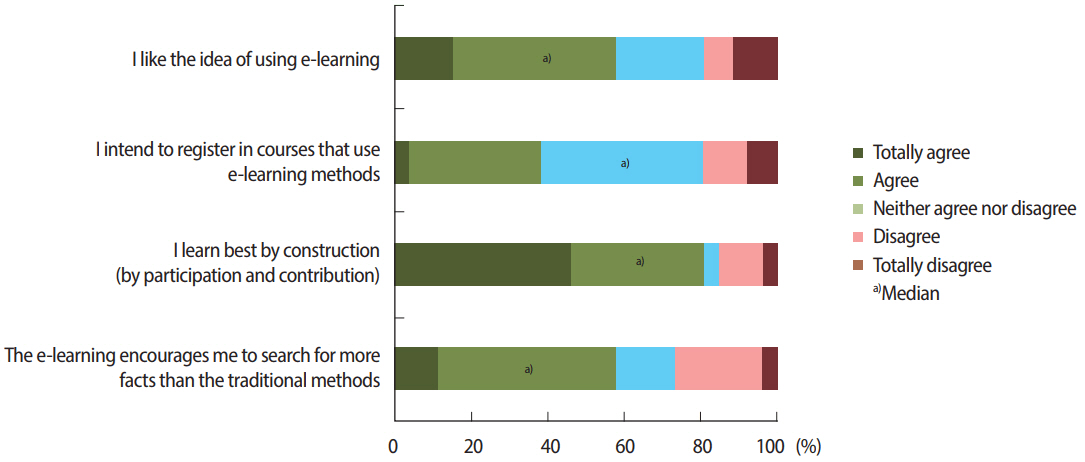

Acceptance of a learning technology affects students' intention to use that technology, but the influence of the acceptance of a learning technology on learning approaches has not been investigated in the literature. A deep learning approach is important in the field of health, where links must be created between skills, knowledge, and habits. Our hypothesis was that acceptance of a hybrid learning model would affect students' way of learning.

METHODS

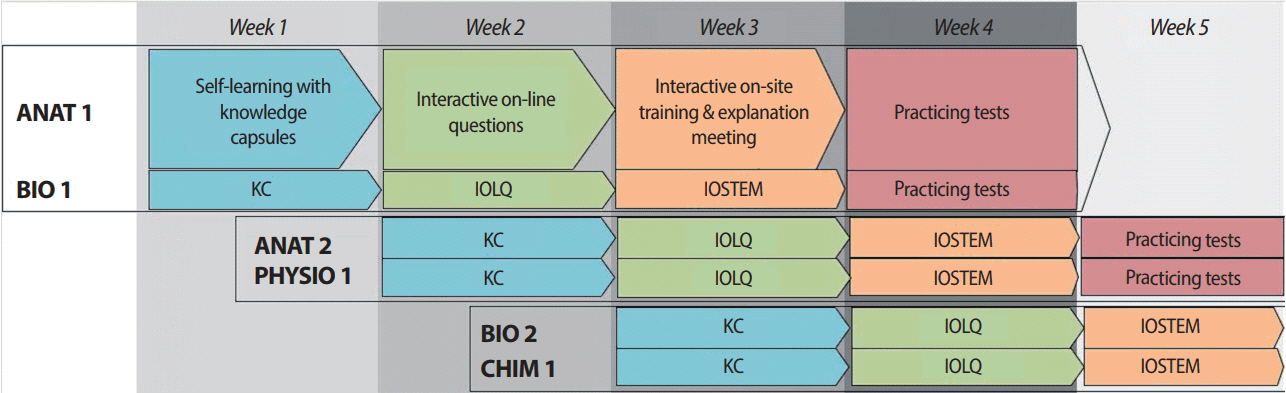

We analysed these concepts, and their correlations, in the context of a flipped classroom method using a local learning management system. In a sample of all students within a single year of study in the midwifery program (n= 38), we used 3 validated scales to evaluate these concepts (the Study Process Questionnaire, My Intellectual Work Tools, and the Hybrid E-Learning Acceptance Model: Learner Perceptions).

RESULTS

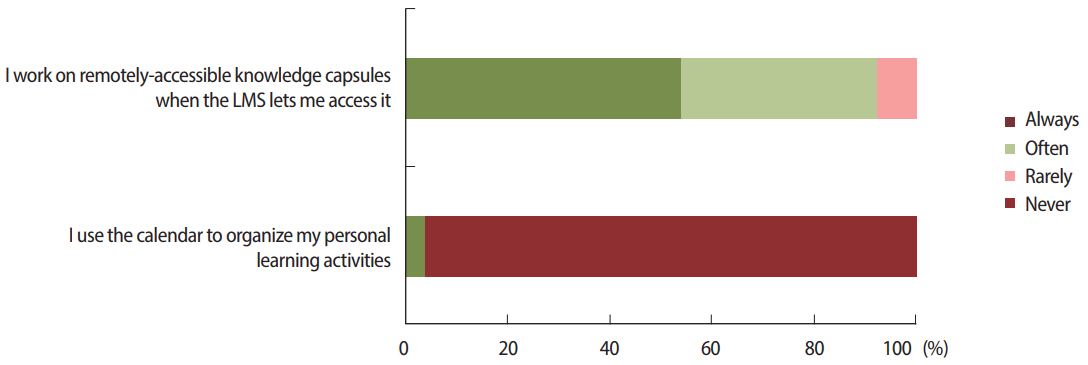

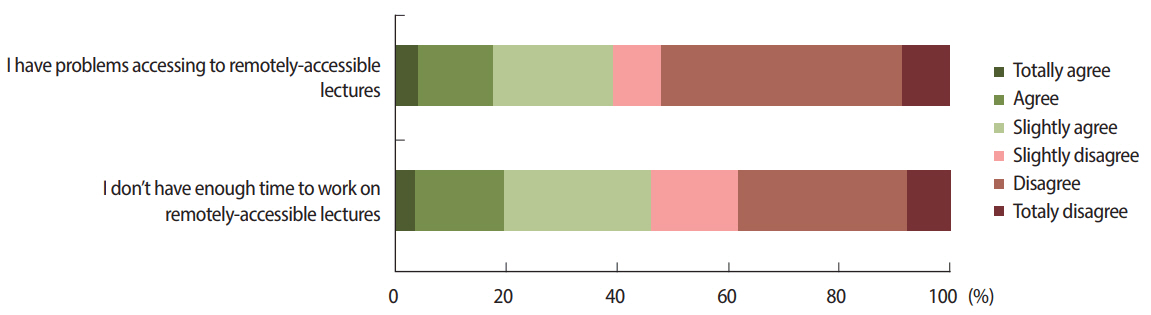

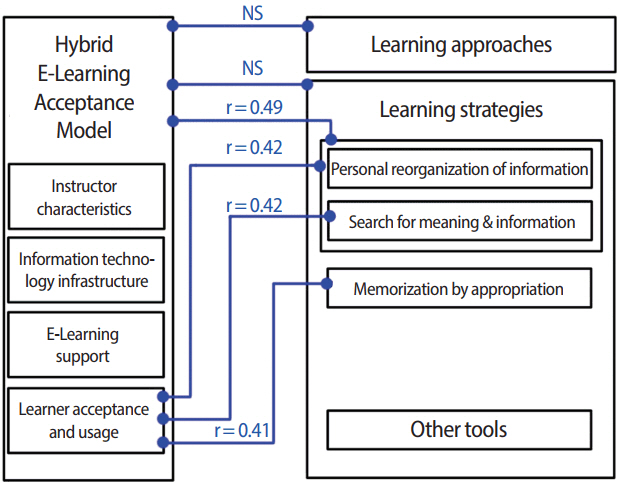

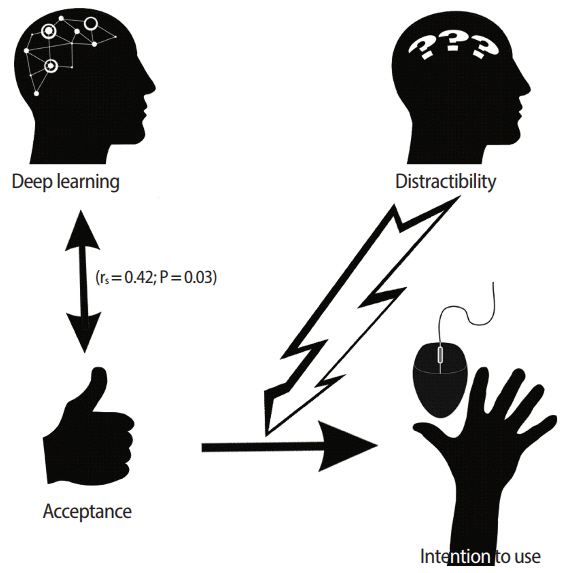

Our sample had a positive acceptance of the learning model, but a neutral intention to use it. Students reported that they were distractible during distance learning. They presented a better mean score for the deep approach than for the superficial approach (P<0.001), which is consistent with their declared learning strategies (personal reorganization of information; search and use of examples). There was no correlation between poor acceptance of the learning model and inadequate learning approaches. The strategy of using deep learning techniques was moderately correlated with acceptance of the learning model (r(s)=0.42, P=0.03).

CONCLUSION

Learning approaches were not affected by acceptance of a hybrid learning model, due to the flexibility of the tool. However, we identified problems in the students' time utilization, which explains their neutral intention to use the system.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Ozkan S, Koseler R. Multi-dimensional students’ evaluation of e-learning systems in the higher education context: an empirical investigation. Comput Educ. 2009; 53:1285–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.011.

Article2. Pierce R, Fox J. Vodcasts and active-learning exercises in a “flipped classroom” model of a renal pharmacotherapy module. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012; 76:196. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7610196.

Article3. Imperial College London; World Health Organization. eLearning for undergraduate health professional education - a systematic review informing a radical transformation of health workforce development [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization, Transformative Education for Health Professionals;2015. [cited 2017 May 20]. Available from: http://whoeducationguidelines.org/content/elearning-report.4. Liu Q, Peng W, Zhang F, Hu R, Li Y, Yan W. The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016; 18:e2. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4807.

Article5. Mayadas AF, Bourne J, Bacsich P. Online education today. Science. 2009; 323:85–89. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1168874.

Article6. Biggs J, Kember D, Leung DY. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br J Educ Psychol. 2001; 71(Pt 1):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158433.

Article7. Ahmed HM. Hybrid e-learning acceptance model: learner perceptions. Decis Sci J Innov Educ. 2010; 8:313–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4609.2010.00259.x.

Article8. Gustin MP, Vinciguerra C, Isaac S, Burillon C, Etienne J. Learning approaches and selection in the common first year of health studies in France. Pedagog Med. 2016; 17:23–43. https://doi.org/10.1051/pmed/2016022.

Article9. Begin C. Les strategies d’apprentissage: un cadre de reference simplifie. Rev Sci Educ. 2008; 34:47–67. https://doi.org/10.7202/018989ar.

Article10. Lopez-Perez MV, Perez-Lopez MC, Rodriguez-Ariza L. Blended learning in higher education: students’ perceptions and their relation to outcomes. Comput Educ. 2011; 56:818–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.10.023.

Article11. Mays KA, Branch-Mays GL. A systematic review of the use of self-assessment in preclinical and clinical dental education. J Dent Educ. 2016; 80:902–913.

Article12. Sharma R, Jain A, Gupta N, Garg S, Batta M, Dhir SK. Impact of self-assessment by students on their learning. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2016; 6:226–229. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.186961.

Article13. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009; 14:595–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2.

Article14. Koh LC. Refocusing formative feedback to enhance learning in preregistration nurse education. Nurse Educ Pract. 2008; 8:223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2007.08.002.

Article15. Gillois P, Bosson JL, Genty C, Vuillez JP, Romanet JP. The impacts of blended learning design in first year medical studies. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015; 210:607–611.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Hybrid Machine Learning Approach To the Promoter Prediction Problem

- A Concept Analysis on Learning Transfer in Nursing Using the Hybrid Model

- The Future of Flexible Learning and Emerging Technology in Medical Education: Reflections from the COVID‐19 Pandemic

- The learning characteristics of primary care physicians

- Effects of Learning Activities on Application of Learning Portfolio in Nursing Management Course