Cancer Res Treat.

2018 Jan;50(1):183-194. 10.4143/crt.2016.532.

The Clinical Significance of Occult Gastrointestinal Primary Tumours in Metastatic Cancer: A Population Retrospective Cohort Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada. mbassamh@uwo.ca

- 2Ivey Business School, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

- 3Department of Oncology, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

- 4Department of Community Health Sciences, College of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

- 5Department of Surgery, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

- 6Department of Radiation Oncology, London Regional Cancer Program, London, ON, Canada.

- 7Department of Biochemistry, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

- 8Institute of Health Policy Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 9Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 10Department of Public Health Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA, USA.

- KMID: 2403488

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2016.532

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to estimate the incidence of occult gastrointestinal (GI) primary tumours in patients with metastatic cancer of uncertain primary origin and evaluate their influence on treatments and overall survival (OS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used population heath data from Manitoba, Canada to identify all patients initially diagnosed with metastatic cancer between 2002 and 2011. We defined patients to have "occult" primary tumour if the primary was found at least 6 months after initial diagnosis. Otherwise, we considered primary tumours as "obvious." We used propensity-score methods to match each patient with occult GI tumour to four patients with obvious GI tumour on all known clinicopathologic features. We compared treatments and 2-year survival data between the two patient groups and assessed treatment effect on OS using Cox regression adjustment.

RESULTS

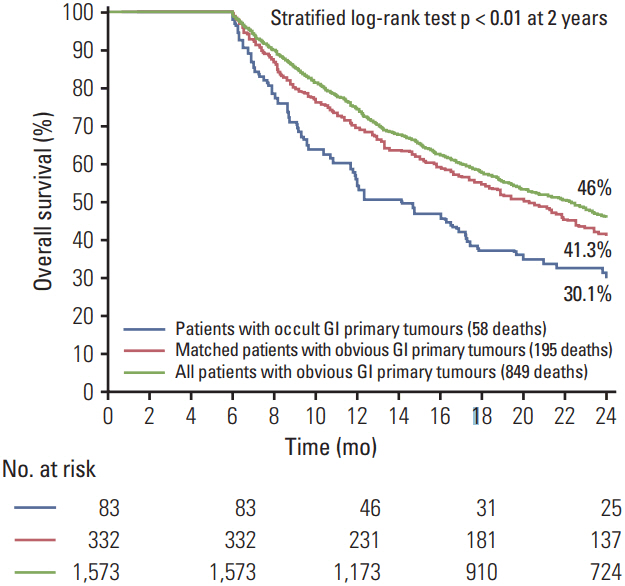

Eighty-three patients had occult GI primary tumours, accounting for 17.6% of men and 14% of women with metastatic cancer of uncertain primary. A 1:4 matching created a matched group of 332 patients with obvious GI primary tumour. Occult cases compared to the matched group were less likely to receive surgical interventions and targeted biological therapy, and more likely to receive cytotoxic empiric chemotherapeutic agents. Having an occult GI tumour was associated with reduced OS and appeared to be a nonsignificant independent predictor of OS when adjusting for treatment differences.

CONCLUSION

GI tumours are the most common occult primary tumours in men and the second most common in women. Patients with occult GI primary tumours are potentially being undertreated with available GI site-specific and targeted therapies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian cancer statistics 2016. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society;2016.2. Coda S, Thillainayagam AV. State of the art in advanced endoscopic imaging for the detection and evaluation of dysplasia and early cancer of the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014; 7:133–50.

Article3. Hainsworth JD, Rubin MS, Spigel DR, Boccia RV, Raby S, Quinn R, et al. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon research institute. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:217–23.

Article4. Varadhachary GR, Talantov D, Raber MN, Meng C, Hess KR, Jatkoe T, et al. Molecular profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary and correlation with clinical evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:4442–8.

Article5. Pentheroudakis G, Greco FA, Pavlidis N. Molecular assignment of tissue of origin in cancer of unknown primary may not predict response to therapy or outcome: a systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009; 35:221–7.

Article6. von Riedenauer WB, Janjua SA, Kwon DS, Zhang Z, Velanovich V. Immunohistochemical identification of primary peritoneal serous cystadenocarcinoma mimicking advanced colorectal carcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007; 1:150.

Article7. Laroia ST, Sasturkar S, Rastogi A, Pamecha V. Solitary hypervascular liver metastasis from neuroendocrine tumor mimicking hepatocellular cancer: all that glitters is not gold. Indian J Nucl Med. 2015; 30:42–6.

Article8. Gunay Y, Demiralay E, Demirag A. Pancreatic metastasis of high-grade papillary serous ovarian carcinoma mimicking primary pancreas cancer: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2012; 2012:943280.

Article9. Kayilioglu SI, Akyol C, Esen E, Cansiz-Ersoz C, Kocaay AF, Genc V, et al. Gastric metastasis of ectopic breast cancer mimicking axillary metastasis of primary gastric cancer. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2014; 2014:232165.10. Mahmud N, Ford JM, Longacre TA, Parent R, Norton JA. Metastatic lobular breast carcinoma mimicking primary signet ring adenocarcinoma in a patient with a suspected CDH1 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:e19–21.

Article11. Abid A, Moffa C, Monga DK. Breast cancer metastasis to the GI tract may mimic primary gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:e106–7.

Article12. Ongom PA, Odida M, Lukande RL, Jombwe J, Elobu E. Metastatic colorectal carcinoma mimicking primary ovarian carcinoma presenting as 'giant' ovarian tumors in an individual with probable Lynch syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013; 7:158.

Article13. Li HC, Schmidt L, Greenson JK, Chang AC, Myers JL. Primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma with intestinal differentiation mimicking metastatic colorectal carcinoma: case report and review of literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009; 131:129–33.14. Benoit MF, Hannigan EV, Smith RP, Smith ER, Byers LJ. Primary gastrointestinal cancers presenting as gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 95:388–92.

Article15. Chhatrala R, Thanavala Y, Iyer R. Targeted therapy in gastrointestinal malignancies. J Carcinog. 2014; 13:4.

Article16. Hannouf MB, Zaric GS. Cost-effectiveness analysis using registry and administrative data. In : Zaric GS, editor. Operations research and health care policy. New York: Springer;2013. p. 341–61.17. Hannouf MB, Brackstone M, Xie B, Zaric GS. Evaluating the efficacy of current clinical practice of adjuvant chemotherapy in postmenopausal women with early-stage, estrogen or progesterone receptor-positive, one-to-three positive axillary lymph node, breast cancer. Curr Oncol. 2012; 19:e319–28.

Article18. Hannouf MB, Xie B, Brackstone M, Zaric GS. Cost effectiveness of a 21-gene recurrence score assay versus Canadian clinical practice in post-menopausal women with early-stage estrogen or progesterone-receptor-positive, axillary lymphnode positive breast cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014; 32:135–47.

Article19. Hannouf MB, Xie B, Brackstone M, Zaric GS. Cost-effectiveness of a 21-gene recurrence score assay versus Canadian clinical practice in women with early-stage estrogen- or progesterone-receptor-positive, axillary lymph-node negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012; 12:447.

Article20. Greco FA, Spigel DR, Yardley DA, Erlander MG, Ma XJ, Hainsworth JD. Molecular profiling in unknown primary cancer: accuracy of tissue of origin prediction. Oncologist. 2010; 15:500–6.

Article21. Hannouf MB, Winquist E, Mahmud SM, Brackstone M, Sarma S, Rodrigues G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using a gene expression profiling test to aid in identifying the primary tumour in patients with cancer of unknown primary. Pharmacogenomics J. 2017; 17:286–300.

Article22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40:373–83.

Article23. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011; 46:399–424.

Article24. Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010; 25:1–21.

Article25. Bridgewater J, van Laar R, Floore A, Van'T Veer L. Gene expression profiling may improve diagnosis in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Br J Cancer. 2008; 98:1425–30.

Article26. Monzon FA, Koen TJ. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: molecular approaches for identification of tissue of origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134:216–24.

Article27. Pillai R, Deeter R, Rigl CT, Nystrom JS, Miller MH, Buturovic L, et al. Validation and reproducibility of a microarray-based gene expression test for tumor identification in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2011; 13:48–56.

Article28. Greco FA. Molecular diagnosis of the tissue of origin in cancer of unknown primary site: useful in patient management. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013; 14:634–42.

Article29. Oien KA, Dennis JL. Diagnostic work-up of carcinoma of unknown primary: from immunohistochemistry to molecular profiling. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23 Suppl 10:x271–7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Evaluation of the Benefit of Radiotherapy in Patients with Occult Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis of the SEER Database

- Three Cases of Primary Spinal Malignant Schwannomas: Case Reports

- Newly-Diagnosed, Histologically-Confirmed Central Nervous System Tumours in a Regional Hospital in Hong Kong : An Epidemiological Study of a 21-Year Period

- A clinical study of metastatic carcinoma to oral soft tissue

- Occult Breast Cancers Manifesting as Axillary Lymph Node Metastasis in Men: A Two-Case Report