Anat Cell Biol.

2017 Dec;50(4):306-309. 10.5115/acb.2017.50.4.306.

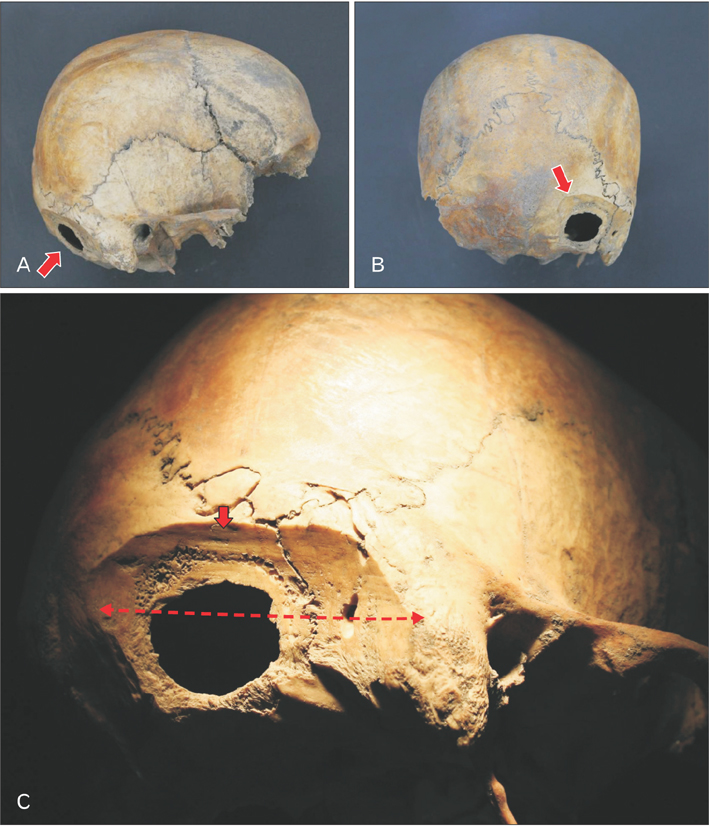

The presence of sharp-edged weapon related cut mark in Joseon skull discovered at the 16th century market district of Old Seoul City ruins in South Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Laboratory of Bioanthropology, Paleopathology and History of Diseases, Department of Anatomy and Institute of Forensic Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. cuteminjae@gmail.com

- 2Ministry of National Defense Agency KIA Recovery & Identification, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Hanul Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Suwon, Korea.

- 4Department of Art History, Myongji University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2399900

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5115/acb.2017.50.4.306

Abstract

- A human skull was discovered at the 16th-century drainage channel of market district ruins, one of the busiest streets in the capital of Joseon kingdom. By anthropological examination, we noticed the cut mark at the right occipital part of the cranium. Judging from the wound property, it might have been caused by a strong strike using a sharp-edged weapon. As no periosteal reaction or healing signs were observed at the cut mark, he might have died shortly after the skull wound was made. We speculated that this might have been of a civilian or soldier victim who died in a battle or the decapitated head of prisoner. This is the first report about the discovery of the skull damaged by sharp-edged weapon at the archaeological sites in the capital city of Joseon Kingdom.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nagaoka T, Uzawa K, Hirata K. Weapon-related traumas of human skeletons from Yuigahama Chusei Shudan Bochi, Japan. Anat Sci Int. 2009; 84:170–181.2. Nagaoka T, Uzawa K, Hirata K. Evidence for weapon-related traumas in medieval Japan: observations of the human crania from Seiyokan. Anthropol Sci. 2010; 118:129–140.3. Ortner DJ. Trauma. In : Ortner DJ, editor. Identification of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Academic Press;2003. p. 119–177.4. Kim YS, Kim MJ, Yu TY, Lee IS, Yi YS, Oh CS, Shin DH. Bioarchaeological investigation of possible gunshot wounds in 18th century human skeletons from Korea. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2013; 23:716–722.5. Kim JH. Analysis of the human remains recovered from Dongrae fortress pond. Dongrae fortress pond II (appendix IV). Busan: Gyeongnam Institute of Cultural Properties;2010. p. 401–435.6. Hanul Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. Archaeological excavation report of the ruins of Jong-gak station improvement project site. Suwon: Hanul Research Institute of Cultural Heritage;2017.7. Buikstra JE, Ubelaker DH. Standards for data collection from human skeletal remains. Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series No. 44. Fayetteville, AK: Arkansas Archaeological Survey;1994.8. Acsadi G, Nemeskeri J. History of human life span and mortality. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado;1970.9. Novak SA. Battle-related trauma. In : Fiorato V, Boylston A, Knusel CJ, editors. Blood Red Roses: The Archaeology of a Mass Grave from the Battle of Towton AD 1461. Oxford: Oxbow Books;2000. p. 90–102.10. Weber J, Czarnetzki A. Brief communication: neurotraumatological aspects of head injuries resulting from sharp and blunt force in the early medieval period of southwestern Germany. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001; 114:352–356.11. Kimmerle EH, Baraybar JP. Skeletal trauma: identification of injuries resulting from human rights abuse and armed conflict. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press;2008.12. Sauer NJ. The timing of injuries and manner of death: distinguishing among antemortem, perimortem and postmortem trauma. In : Reichs KJ, editor. Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains. 2nd ed. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas;1998. p. 321–332.13. Wenham SJ. Anatomical interpretations of Anglo-Saxon weapon injuries. In : Chadwick Hawkes S, editor. Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph No. 21. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology;1989. p. 123–139.14. Morimoto I. Note on the technique of decapitation in medieval Japan. J Anthropol Soc Nippon. 1987; 95:477–486.15. Morimoto I, Hirata K. A decapitated human skull from medieval Kamakura. Anthropol Soc Nippon. 1992; 100:349–358.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Forensic Anthropological Study on Saw Marks Appearing on the Tibiae of a Joseon Skeleton

- The Indigenization of Licorice and Its Meaning During the Early Days of the Joseon Dynasty

- Stable isotope analysis of Joseon people skeletons from the cemeteries of Old Seoul City, the capital of Joseon Dynasty

- The Change of the Status of Joseon Medical Bureaucrats in the 15th and 16th Centuries

- Animal Bones Found at Gongpyeong-dong Archaeological Site, the Capital Area of Joseon Dynasty Period