Infect Chemother.

2017 Dec;49(4):301-325. 10.3947/ic.2017.49.4.301.

Clinical Guidelines for the Antibiotic Treatment for Community-Acquired Skin and Soft Tissue Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea. sangho@amc.seoul.kr

- 3The Korean Society for Chemotherapy, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Chung Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Department of Internal Medicne, SoonChunHyang University Bucheon Hospital, Buchon, Korea.

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguk University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea.

- 7The Korean Dermatological Association, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Department of Dermatology, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 9The Korean Orthopaedic Association, Seoul, Korea.

- 10Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 11Department of Infectious Diseases, Ulsan University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2399200

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2017.49.4.301

Abstract

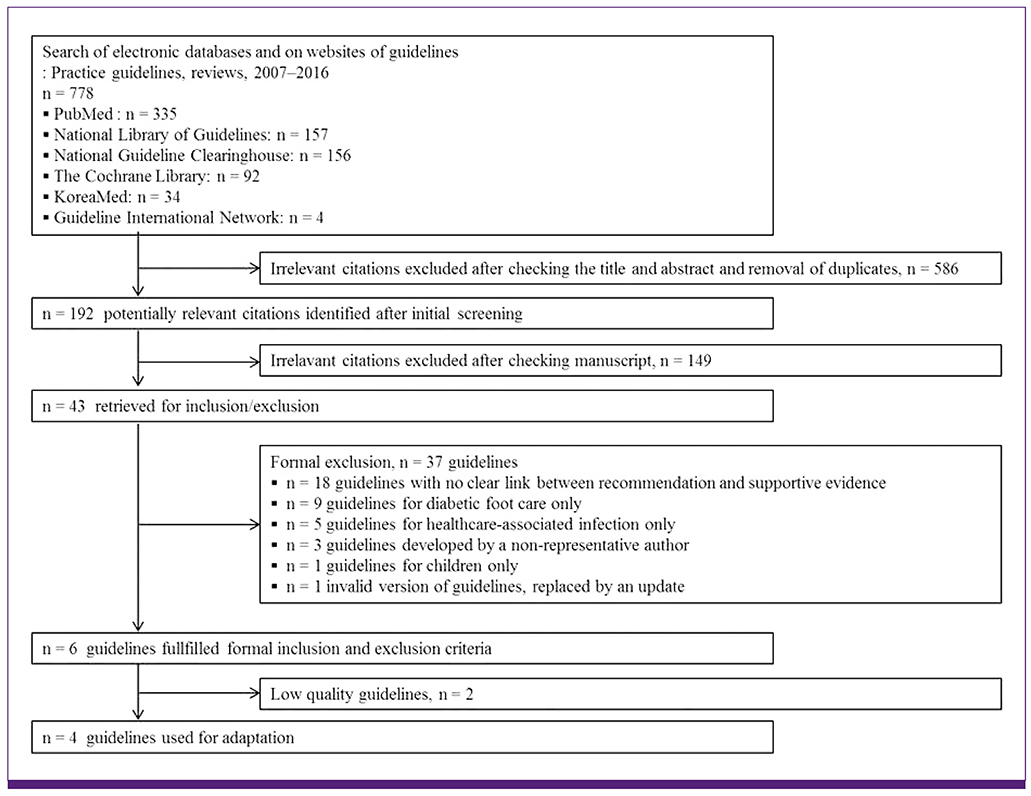

- Skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) is common and important infectious disease. This work represents an update to 2012 Korean guideline for SSTI. The present guideline was developed by the adaptation method. This clinical guideline provides recommendations for the diagnosis and management of SSTI, including impetigo/ecthyma, purulent skin and soft tissue infection, erysipelas and cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, pyomyositis, clostridial myonecrosis, and human/animal bite. This guideline targets community-acquired skin and soft tissue infection occurring among adult patients aged 16 years and older. Diabetic foot infection, surgery-related infection, and infections in immunocompromised patients were not included in this guideline.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

A Case of

Bergeyella zoohelcum Isolated from a Patient with Cellulitis after a Dog Bite

Kiwook Jung, Jae Hyeon Park, Chang Kyung Kang, Taek Soo Kim, Hyunwoong Park

Lab Med Online. 2020;11(1):73-77. doi: 10.47429/lmo.2021.11.1.73.Principles of selecting appropriate antimicrobial agents

Su-Mi Choi, Dong-Gun Lee

J Korean Med Assoc. 2019;62(6):335-344. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2019.62.6.335.Microbiology and Antimicrobial Therapy for Diabetic Foot Infections

Ki Tae Kwon, David G. Armstrong

Infect Chemother. 2018;50(1):11-20. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.1.11.

Reference

-

1. May AK, Stafford RE, Bulger EM, Heffernan D, Guillamondegui O, Bochicchio G, Eachempati SR; Surgical Infection Society. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2009; 10:467–499.

Article2. Esposito S, Bassetti M, Borre’ S, Bouza E, Dryden M, Fantoni M, Gould IM, Leoncini F, Leone S, Milkovich G, Nathwani D, Segreti J, Sganga G, Unal S, Venditti M; Italian Society of Infectious Tropical Diseases. International Society of Chemotherapy. Diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTI): a literature review and consensus statement on behalf of the Italian Society of Infectious Diseases and International Society of Chemotherapy. J Chemother. 2011; 23:251–262.

Article3. The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, The Korean Society for Chemotherapy, The Korean Orthopaedic Association, The Korean Society of Clinical Microbiology, The Korean Dermatologic Association. Clinical practice guidelines for soft tissue infections. Infect Chemother. 2012; 44:213–232.4. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan SL, Montoya JG, Wade JC; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 59:e10–e52.

Article5. Sartelli M, Malangoni MA, May AK, Viale P, Kao LS, Catena F, Ansaloni L, Moore EE, Moore FA, Peitzman AB, Coimbra R, Leppaniemi A, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Koike K, Girardis M, Ordonez CA, Tavola M, Cainzos M, Di Saverio S, Fraga GP, Gerych I, Kelly MD, Taviloglu K, Wani I, Marwah S, Bala M, Ghnnam W, Shaikh N, Chiara O, Faro MP Jr, Pereira GA Jr, Gomes CA, Coccolini F, Tranà C, Corbella D, Brambillasca P, Cui Y, Segovia Lohse HA, Khokha V, Kok KY, Hong SK, Yuan KC. World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) guidelines for management of skin and soft tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2014; 9:57.

Article6. Japanese Society of Chemotherapy Committee on guidelines for treatment of anaerobic infections; Japanese Association of Anaerobic Infections Research. Chapter 2-5-3a. Anaerobic infections (individual fields): skin and soft tissue infections. J Infect Chemother. 2011; 17:Suppl 1. 72–76.7. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008; 336:924–926.

Article8. Pasternack MS, Swartz MN. Cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and subcutaneous tissue infections. In : Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone;2015. p. 1194–1215.9. Durupt F, Mayor L, Bes M, Reverdy ME, Vandenesch F, Thomas L, Etienne J. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus toxins and nasal carriage in furuncles and impetigo. Br J Dermatol. 2007; 157:1161–1167.

Article10. Hirschmann JV. Impetigo: etiology and therapy. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 2002; 42–51.11. Koning S, van der Wouden JC, Chosidow O, Twynholm M, Singh KP, Scangarella N, Oranje AP. Efficacy and safety of retapamulin ointment as treatment of impetigo: randomized double‐blind multicentre placebo‐controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2008; 158:1077–1082.

Article12. Koning S, van der Sande R, Verhagen AP, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Morris AD, Butler CC, Berger M, van der Wouden JC. Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 1:CD003261.

Article13. Wasserzug O, Valinsky L, Klement E, Bar-Zeev Y, Davidovitch N, Orr N, Korenman Z, Kayouf R, Sela T, Ambar R, Derazne E, Dagan R, Zarka S. A cluster of ecthyma outbreaks caused by a single clone of invasive and highly infective Streptococcus pyogenes. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 48:1213–1219.

Article14. Bae EY, Lee JD, Cho SH. Isolation of causative microorganism and antimicrobial susceptibility in impetigo. Korean J Dermatol. 2003; 41:1278–1285.15. Kim WJ, Lee KR, Lee SE, Lee HJ, Yoon MS. Isolation of the causative microorganism and antimicrobial susceptibility of impetigo. Korean J Dermatol. 2012; 50:788–794.16. Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Talan DA. EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:666–674.

Article17. Rahimian J, Khan R, LaScalea KA. Does nasal colonization or mupirocin treatment affect recurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and skin structure infections? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007; 28:1415–1416.

Article18. Ellis MW, Griffith ME, Dooley DP, McLean JC, Jorgensen JH, Patterson JE, Davis KA, Hawley JS, Regules JA, Rivard RG, Gray PJ, Ceremuga JM, Dejoseph MA, Hospenthal DR. Targeted intranasal mupirocin to prevent colonization and infection by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in soldiers: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 51:3591–3598.

Article19. Whitman TJ, Herlihy RK, Schlett CD, Murray PR, Grandits GA, Ganesan A, Brown M, Mancuso JD, Adams WB, Tribble DR. Chlorhexidine-impregnated cloths to prevent skin and soft-tissue infection in Marine recruits: a cluster-randomized, double-blind, controlled effectiveness trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010; 31:1207–1215.

Article20. Wiese-Posselt M, Heuck D, Draeger A, Mielke M, Witte W, Ammon A, Hamouda O. Successful termination of a furunculosis outbreak due to lukS-lukF–positive, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a German village by stringent decolonization, 2002-2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44:e88–e95.

Article21. Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, Eisenstein KA, Rodriguez M, Epplin EK, Garbutt J, Fraser VJ. Household versus individual approaches to eradication of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in children: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 54:743–751.

Article22. Bisno AL, Stevens DL. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:240–245.

Article23. Perl B, Gottehrer NP, Raveh D, Schlesinger Y, Rudensky B, Yinnon AM. Cost-effectiveness of blood cultures for adult patients with cellulitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 29:1483–1488.

Article24. Hook EW 3rd, Hooton TM, Horton CA, Coyle MB, Ramsey PG, Turck M. Microbiologic evaluation of cutaneous cellulitis in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146:295–297.

Article25. Kielhofner MA, Brown B, Dall L. Influence of underlying disease process on the utility of cellulitis needle aspirates. Arch Intern Med. 1988; 148:2451–2452.

Article26. Duvanel T, Auckenthaler R, Rohner P, Harms M, Saurat JH. Quantitative cultures of biopsy specimens from cutaneous cellulitis. Arch Intern Med. 1989; 149:293–296.

Article27. Eriksson B, Jorup-Rönström C, Karkkonen K, Sjöblom AC, Holm SE. Erysipelas: clinical and bacteriologic spectrum and serological aspects. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 23:1091–1098.

Article28. Kwak YG, Kim NJ, Choi SH, Choi SH, Chung JW, Choo EJ, Kim KH, Yun NR, Lee S, Kwon KT, Cho JH. Clinical characteristics and organisms causing erysipelas and cellulitis. Infect Chemother. 2012; 44:45–50.

Article29. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Everett ED, Dellinger P, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan EL, Montoya JG, Wade JC; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:1373–1406.

Article30. Bernard P, Bedane C, Mounier M, Denis F, Catanzano G, Bonnetblanc JM. Streptococcal cause of erysipelas and cellulitis in adults. A microbiologic study using a direct immunofluorescence technique. Arch Dermatol. 1989; 125:779–782.

Article31. Park SY, Kim T, Choi SH. Jung J, Yu SN, Hong H-L, Kim YK, Park SY, Song EH, Park K-H, Cho OH, Choi SH, Kwak YG, and the Korean SSTI (Skin and Soft Tissue Infection) Study Group. A multicenter study of clinical features and organisms causing community-onset cellulitis in Korea. [abstract]. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017; 50:Suppl 1. S75.32. Chan JC. Ampicillin/sulbactam versus cefazolin or cefoxitin in the treatment of skin and skin-structure infections of bacterial etiology. Adv Ther. 1995; 12:139–146.33. Jeng A, Beheshti M, Li J, Nathan R. The role of beta-hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis: a prospective investigation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010; 89:217–226.

Article34. Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, Ellis MW, Starnes WF, Hasewinkle WC. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004; 164:1669–1674.

Article35. Dupuy A, Benchikhi H, Roujeau JC, Bernard P, Vaillant L, Chosidow O, Sassolas B, Guillaume JC, Grob JJ, Bastuji-Garin S. Risk factors for erysipelas of the leg (cellulitis): case-control study. BMJ. 1999; 318:1591–1594.

Article36. Björnsdóttir S, Gottfredsson M, Thórisdóttir AS, Gunnarsson GB, Ríkardsdóttir H, Kristjánsson M, Hilmarsdóttir I. Risk factors for acute cellulitis of the lower limb: a prospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:1416–1422.

Article37. Jorup-Rönström C, Britton S. Recurrent erysipelas: predisposing factors and costs of prophylaxis. Infection. 1987; 15:105–106.

Article38. McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Martinez J, Mirzoyev SA, Baddour LM. A predictive model of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a population-based cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167:709–715.

Article39. Lewis SD, Peter GS, Gómez-Marín O, Bisno AL. Risk factors for recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a U.S. Veterans Medical Center population. Am J Med Sci. 2006; 332:304–307.

Article40. Karppelin M, Siljander T, Vuopio-Varkila J, Kere J, Huhtala H, Vuento R, Jussila T, Syrjänen J. Factors predisposing to acute and recurrent bacterial non-necrotizing cellulitis in hospitalized patients: a prospective case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010; 16:729–734.

Article41. Pavlotsky F, Amrani S, Trau H. Recurrent erysipelas: risk factors. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2004; 2:89–95.42. Sjöblom AC, Eriksson B, Jorup-Rönström C, Karkkonen K, Lindqvist M. Antibiotic prophylaxis in recurrent erysipelas. Infection. 1993; 21:390–393.

Article43. Kremer M, Zuckerman R, Avraham Z, Raz R. Long-term antimicrobial therapy in the prevention of recurrent soft-tissue infections. J Infect. 1991; 22:37–40.

Article44. UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network's PATCH Trial Team. Thomas K, Crook A, Foster K, Mason J, Chalmers J, Bourke J, Ferguson A, Level N, Nunn A, Williams H. Prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of cellulitis (erysipelas) of the leg: results of the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network's PATCH II trial. Br J Dermatol. 2012; 166:169–178.45. Thomas KS, Crook AM, Nunn AJ, Foster KA, Mason JM, Chalmers JR, Nasr IS, Brindle RJ, English J, Meredith SK, Reynolds NJ, de Berker D, Mortimer PS, Williams HC. U.K. Dermatology Clinical Trials Network's PATCH I Trial Team. Penicillin to prevent recurrent leg cellulitis. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:1695–1703.46. Wang JH, Liu YC, Cheng DL, Yen MY, Chen YS, Wang JH, Wann SR, Lin HH. Role of benzathine penicillin G in prophylaxis for recurrent streptococcal cellulitis of the lower legs. Clin Infect Dis. 1997; 25:685–689.

Article47. Choi SH, Choi SH, Kwak YG, Chung JW, Choo EJ, Kim KH, Yun NR, Lee S, Kwon KT, Cho JH, Kim NJ. Clinical characteristics and causative organisms of community-acquired necrotizing fasciitis. Infect Chemother. 2012; 44:180–184.

Article48. Kim T, Park SY, Gwak YG, Choi SH. Jung J, You SN, Hong H-L, Kim YK, Park SY, Song EH, Park K-H, Cho OH, Choi SH, and the Korean SSTI (Skin and Soft Tissue Infection) Study Group. A multicenter study of clinical characteristics and microbial etiology in commmunity-onset necrotizing fasciitis in Korea. [abstract]. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017; 50:Suppl 1. S136.49. Wang YS, Wong CH, Tay YK. Staging of necrotizing fasciitis based on the evolving cutaneous features. Int J Dermatol. 2007; 46:1036–1041.

Article50. Schmid MR, Kossmann T, Duewell S. Differentiation of necrotizing fasciitis and cellulitis using MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998; 170:615–620.

Article51. Becker M, Zbären P, Hermans R, Becker CD, Marchal F, Kurt AM, Marré S, Rüfenacht DA, Terrier F. Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck: role of CT in diagnosis and management. Radiology. 1997; 202:471–476.

Article52. Arslan A, Pierre-Jerome C, Borthne A. Necrotizing fasciitis: unreliable MRI findings in the preoperative diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2000; 36:139–143.

Article53. Kao LS, Lew DF, Arab SN, Todd SR, Awad SS, Carrick MM, Corneille MG, Lally KP. Local variations in the epidemiology, microbiology, and outcome of necrotizing soft-tissue infections: a multicenter study. Am J Surg. 2011; 202:139–145.

Article54. Zimbelman J, Palmer A, Todd J. Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999; 18:1096–1100.

Article55. Mulla ZD, Leaverton PE, Wiersma ST. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Florida. South Med J. 2003; 96:968–973.

Article56. Ardanuy C, Domenech A, Rolo D, Calatayud L, Tubau F, Ayats J, Martín R, Liñares J. Molecular characterization of macrolide- and multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from adult patients in Barcelona, Spain (1993-2008). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010; 65:634–643.

Article57. Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-A:1454–1460.58. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996; 224:672–683.59. Voros D, Pissiotis C, Georgantas D, Katsaragakis S, Antoniou S, Papadimitriou J. Role of early and extensive surgery in the treatment of severe necrotizing soft tissue infection. Br J Surg. 1993; 80:1190–1191.

Article60. Darabi K, Abdel-Wahab O, Dzik WH. Current usage of intravenous immune globulin and the rationale behind it: the Massachusetts General Hospital data and a review of the literature. Transfusion. 2006; 46:741–753.

Article61. Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, Kotb M, Schwartz B, O'Rourke K, Talbot J, Low DE. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome--a comparative observational study. The Canadian Streptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:800–807.

Article62. Norrby-Teglund A, Ihendyane N, Darenberg J. Intravenous immunoglobulin adjunctive therapy in sepsis, with special emphasis on severe invasive group A streptococcal infections. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003; 35:683–689.

Article63. Darenberg J, Ihendyane N, Sjölin J, Aufwerber E, Haidl S, Follin P, Andersson J, Norrby-Teglund A. StreptIg Study Group. Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a European randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 37:333–340.

Article64. Kim T, Park SY, Gwak YG, Choi SH. Jung J, You SN, Hong H-L, Kim YK, Park SY, Song EH, Park K-H, Cho OH, Choi SH, and the Korean SSTI (Skin and Soft Tissue Infection) Study Group. A multicenter study of clinical characteristics and microbial etiology in community-onset pyomyositis in Korea. [abstract]. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017; 50:Suppl 1. S136.65. Yu JS, Habib P. MR imaging of urgent inflammatory and infectious conditions affecting the soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system. Emerg Radiol. 2009; 16:267–276.

Article66. Turecki MB, Taljanovic MS, Stubbs AY, Graham AR, Holden DA, Hunter TB, Rogers LF. Imaging of musculoskeletal soft tissue infections. Skeletal Radiol. 2010; 39:957–971.

Article67. Crum NF. Bacterial pyomyositis in the United States. Am J Med. 2004; 117:420–428.

Article68. Chiu SK, Lin JC, Wang NC, Peng MY, Chang FY. Impact of underlying diseases on the clinical characteristics and outcome of primary pyomyositis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008; 41:286–293.69. Faraklas I, Stoddard GJ, Neumayer LA, Cochran A. Development and validation of a necrotizing soft-tissue infection mortality risk calculator using NSQIP. J Am Coll Surg. 2013; 217:153–160.e3. discussion 160-1.

Article70. Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Clostridial myonecrosis: new insights in pathogenesis and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010; 12:383–391.

Article71. Stevens DL, Maier KA, Laine BM, Mitten JE. Comparison of clindamycin, rifampin, tetracycline, metronidazole, and penicillin for efficacy in prevention of experimental gas gangrene due to Clostridium perfringens. J Infect Dis. 1987; 155:220–228.

Article72. Stevens DL, Laine BM, Mitten JE. Comparison of single and combination antimicrobial agents for prevention of experimental gas gangrene caused by Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:312–316.

Article73. Broder J, Jerrard D, Olshaker J, Witting M. Low risk of infection in selected human bites treated without antibiotics. Am J Emerg Med. 2004; 22:10–13.

Article74. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001; CD001738.

Article75. Zubowicz VN, Gravier M. Management of early human bites of the hand: a prospective randomized study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991; 88:111–114.76. Cummings P. Antibiotics to prevent infection in patients with dog bite wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Emerg Med. 1994; 23:535–540.

Article77. Callaham M. Prophylactic antibiotics in common dog bite wounds: a controlled study. Ann Emerg Med. 1980; 9:410–414.

Article78. Dire DJ. Emergency management of dog and cat bite wounds. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1992; 10:719–736.

Article79. Elenbaas RM, McNabney WK, Robinson WA. Prophylactic oxacillin in dog bite wounds. Ann Emerg Med. 1982; 11:248–251.

Article80. Dire DJ, Hogan DE, Walker JS. Prophylactic oral antibiotics for low-risk dog bite wounds. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1992; 8:194–199.

Article81. Abrahamian FM, Goldstein EJ. Microbiology of animal bite wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011; 24:231–246.

Article82. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Wield B, Blachman U, Sutter VL, Miller TA, Finegold SM. Bacteriology of human and animal bite wounds. J Clin Microbiol. 1978; 8:667–672.

Article83. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM. Comparative activities of cefuroxime, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, enoxacin, and ofloxacin against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria isolated from bite wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1143–1148.

Article84. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Finegold SM. Dog bite wounds and infection: a prospective clinical study. Ann Emerg Med. 1980; 9:508–512.

Article85. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Richwald GA. Lack of in vitro efficacy of oral forms of certain cephalosporins, erythromycin, and oxacillin against Pasteurella multocida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:213–215.

Article86. Stevens DL, Higbee JW, Oberhofer TR, Everett ED. Antibiotic susceptibilities of human isolates of Pasteurella multocida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979; 16:322–324.

Article87. Muguti GI, Dixon MS. Tetanus following human bite. Br J Plast Surg. 1992; 45:614–615.

Article88. Talan DA, Citron DM, Abrahamian FM, Moran GJ, Goldstein EJ. Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. Emergency Medicine Animal Bite Infection Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:85–92.

Article89. Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcuse EK, Pickering LK; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006; 55:1–48.90. Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). Guideline for rabies control 2017. Accessed 22 December, 2017. Available at: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/notice/CdcKrTogether0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1154-U0005-MNU0088&cid=75073.91. Rupprecht CE, Briggs D, Brown CM, Franka R, Katz SL, Kerr HD, Lett SM, Levis R, Meltzer MI, Schaffner W, Cieslak PR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of a reduced (4-dose) vaccine schedule for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent human rabies: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59:1–9.92. Zook EG, Miller M, Van Beek AL, Wavak P. Successful treatment protocol for canine fang injuries. J Trauma. 1980; 20:243–247.

Article93. Schultz RC, McMaster WC. The treatment of dog bite injuries, especially those of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972; 49:494–500.

Article94. Chen E, Hornig S, Shepherd SM, Hollander JE. Primary closure of mammalian bites. Acad Emerg Med. 2000; 7:157–161.

Article95. Maimaris C, Quinton DN. Dog-bite lacerations: a controlled trial of primary wound closure. Arch Emerg Med. 1988; 5:156–161.

Article