Tuberc Respir Dis.

2017 Jan;80(1):21-26. 10.4046/trd.2017.80.1.21.

Preventing the Transmission of Tuberculosis in Health Care Settings: Administrative Control

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. heathcliff6800@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2396337

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2017.80.1.21

Abstract

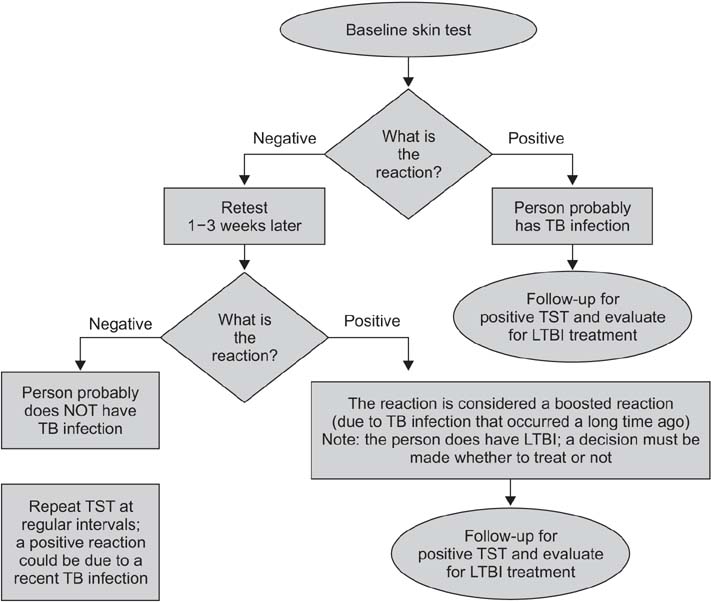

- It is well established that health care workers (HCWs) have a considerably higher risk of occupationally acquired tuberculosis (TB). To reduce the transmission of TB to HCWs and patients, TB infection control programs should be implemented in health care settings. The first and most important level of all protection and control programs is administrative control. Its goals are to prevent HCWs, other staff, and patients from being exposed to TB, and to reduce the transmission of infection by ensuring rapid diagnosis and treatment of affected individuals. Administrative control measures recommended by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization include prompt identification of people with TB symptoms, isolation of infectious patients, control of the spread of the pathogen, and minimization of time spent in health care facilities. Another key component of measures undertaken is the baseline and serial screening for latent TB infection in HCWs who are at risk of exposure to TB. Although the interferon-gamma release assay has some advantages over the tuberculin skin test, the former has serious limitations, mostly due to its high conversion rate.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Latent Tuberculosis Infection among Health Care Workers Working in a Tertiary Hospital in South Korea

Jae Seuk Park

Tuberc Respir Dis. 2018;81(4):274-280. doi: 10.4046/trd.2018.0020.

Reference

-

1. Jensen PA, Lambert LA, Iademarco MF, Ridzon R. CDC. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005; 54:1–141.2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Core curriculum on tuberculosis: what the clinicians should know [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2013. cited 2016 Sep 1. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/education/corecurr/pdf/corecurr_all.pdf.3. World Health Organization. WHO policy on TB infection control in health-care facilities, congregate settings and households [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2009. cited 2016 Sep 1. Available from: http://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/en/.4. Pai M, Kunimoto D, Jamieson F, Menzies D. Canadian tuberculsosis standards, 7th edition. Diagnosis latent tuberculosis infection. Can Respir J. 2013; 20:Suppl A. 23A–34A.5. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Elimination of Tuberculosis in the United States. Geiter L. Ending neglect: the elimination of tuberculosis in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2000.6. Verkuijl S, Middelkoop K. Protecting our front-liners: occupational tuberculosis prevention through infection control strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 62:Suppl 3. S231–S237.7. Meredith S, Watson JM, Citron KM, Cockcroft A, Darbyshire JH. Are healthcare workers in England and Wales at increased risk of tuberculosis? BMJ. 1996; 313:522–525.8. Chu H, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, Kuo SC, Hsu YT, Ou SM, et al. Risk of tuberculosis among healthcare workers in an intermediate-burden country: a nationwide population study. J Infect. 2014; 69:525–532.9. Jo KW, Woo JH, Hong Y, Choi CM, Oh YM, Lee SD, et al. Incidence of tuberculosis among health care workers at a private university hospital in South Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12:436–440.10. Menzies D, Joshi R, Pai M. Risk of tuberculosis infection and disease associated with work in health care settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007; 11:593–605.11. Casas I, Esteve M, Guerola R, Garcia-Olive I, Roldan-Merino J, Martinez-Rivera C, et al. Incidence of tuberculosis infection among healthcare workers: risk factors and 20-year evolution. Respir Med. 2013; 107:601–607.12. Lee K, Han MK, Choi HR, Choi CM, Oh YM, Lee SD, et al. Annual incidence of latent tuberculosis infection among newly employed nurses at a tertiary care university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009; 30:1218–1222.13. Sutherland I. Recent studies in the epidemiology of tuberculosis, based on the risk of being infected with tubercle bacilli. Adv Tuberc Res. 1976; 19:1–63.14. Sutherland I. The evolution of clinical tuberculosis in adolescents. Tuberculosis. 1966; 47:308.15. Lobue P, Menzies D. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Respirology. 2010; 15:603–622.16. Clinical practice guideline for tuberculosis [Internet]. Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee;2011. cited 2016 Sep 1. Available from: http://www.lungkorea.org/image/mail/file_110217.pdf.17. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000; 49:1–51.18. Snider DE Jr, Cauthen GM. Tuberculin skin testing of hospital employees: infection, “boosting,” and two-step testing. Am J Infect Control. 1984; 12:305–311.19. Kim SY, Park MS, Kim YS, Kim SK, Chang J, Yong D, et al. Tuberculin skin test and boosted reactions among newly employed healthcare workers: an observational study. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e64563.20. Fong KS, Tomford JW, Teixeira L, Fraser TG, van Duin D, Yen-Lieberman B, et al. Challenges of interferon-gamma release assay conversions in serial testing of health-care workers in a TB control program. Chest. 2012; 142:55–62.21. Slater ML, Welland G, Pai M, Parsonnet J, Banaei N. Challenges with QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay for large-scale, routine screening of U.S. healthcare workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 188:1005–1010.22. Dorman SE, Belknap R, Graviss EA, Reves R, Schluger N, Weinfurter P, et al. Interferon-gamma release assays and tuberculin skin testing for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 189:77–87.23. Park JS, Lee JS, Kim MY, Lee CH, Yoon HI, Lee SM, et al. Monthly follow-ups of interferon-gamma release assays among health-care workers in contact with patients with TB. Chest. 2012; 142:1461–1468.24. Metcalfe JZ, Cattamanchi A, McCulloch CE, Lew JD, Ha NP, Graviss EA. Test variability of the QuantiFERON-TB gold intube assay in clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 187:206–211.25. King TC, Upfal M, Gottlieb A, Adamo P, Bernacki E, Kadlecek CP, et al. T-SPOT.TB interferon-gamma release assay performance in healthcare worker screening at nineteen U.S. hospitals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192:367–373.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Tuberculosis Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities: Environmental Control and Personal Protection

- Prevention of tuberculosis and isolation of tuberculosis patients in health care facilities

- Tuberculosis Infection and Latent Tuberculosis

- How to Prevent Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings

- Management of multi-drug resistant organisms in healthcare settings