Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2017 Sep;60(5):440-448. 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.5.440.

Nomogram predicting risk of lymphocele in gynecologic cancer patients undergoing pelvic lymph node dissection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- KMID: 2393843

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2017.60.5.440

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study is to estimate the risk of postoperative lymphocele development after lymphadenectomy in gynecologic cancer patients through establishing a nomogram.

METHODS

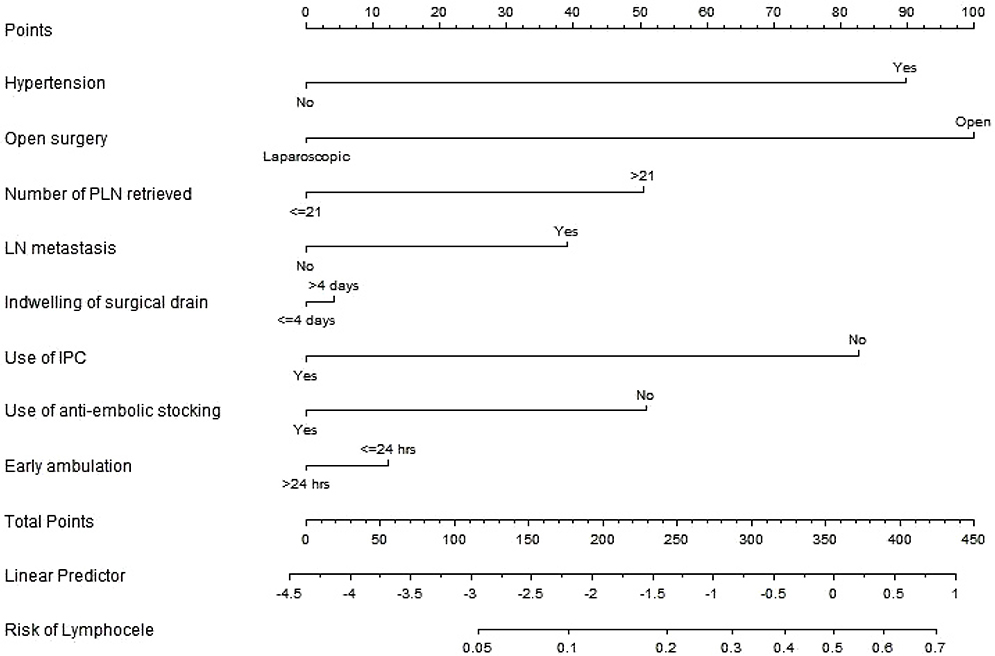

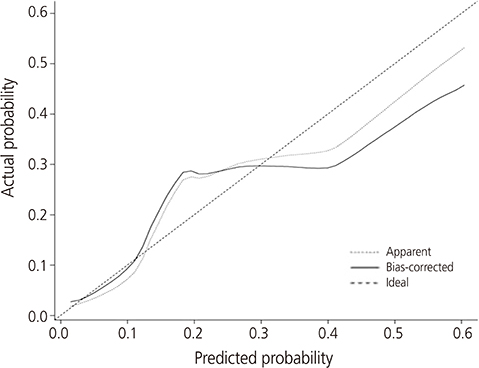

We retrospectively reviewed 371 consecutive gynecologic cancer patients undergoing lymphadenectomy between 2009 and 2014. Association of the development of postoperative lymphocele with clinical characteristics was evaluated in univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Nomograms were built based on the data of multivariate analysis using R-software.

RESULTS

Mean age at the operation was 50.8±11.1 years. Postoperative lymphocele was found in 70 (18.9%) patients. Of them, 22 (31.4%) had complicated one. Multivariate analysis revealed that hypertension (hazard ratio [HR], 3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 to 6.0; P=0.003), open surgery (HR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.4 to 7.1; P=0.004), retrieved lymph nodes (LNs) >21 (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0 to 3.3; P=0.042), and no use of intermittent pneumatic compression (HR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.0 to 7.2; P=0.047) were independent risk factors for the development of postoperative lymphocele. The nomogram appeared to be accurate and predicted the lymphocele development better than chance (concordance index, 0.754). For complicated lymphoceles, most variables which have shown significant association with general lymphocele lost the statistical significance, except hypertension (P=0.011) and mean number of retrieved LNs (29.5 vs. 21.1; P=0.001). A nomogram for complicated lymphocele showed similar predictive accuracy (concordance index, 0.727).

CONCLUSION

We developed a nomogram to predict the risk of lymphocele in gynecologic cancer patients on the basis of readily obtained clinical variables. External validation of this nomogram in different group of patients is needed.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hiramatsu K, Kobayashi E, Ueda Y, Egawa-Takata T, Matsuzaki S, Kimura T, et al. Optimal timing for drainage of infected lymphocysts after lymphadenectomy for gynecologic cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015; 25:337–341.2. Gallotta V, Fanfani F, Rossitto C, Vizzielli G, Testa A, Scambia G, et al. A randomized study comparing the use of the Ligaclip with bipolar energy to prevent lymphocele during laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy for gynecologic cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 203:483.3. Kim YH, Shin HJ, Ju W, Kim SC. Prevention of lymphocele by using gelatin-thrombin matrix as a tissue sealant after pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with gynecologic cancers: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017; 28:e37.4. Kim HY, Kim JW, Kim SH, Kim YT, Kim JH. An analysis of the risk factors and management of lymphocele after pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with gynecologic malignancies. Cancer Res Treat. 2004; 36:377–383.5. Charoenkwan K, Kietpeerakool C. Retroperitoneal drainage versus no drainage after pelvic lymphadenectomy for the prevention of lymphocyst formation in patients with gynaecological malignancies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (6):CD007387.6. Mori N. Clinical and experimental studies on the socalled lymphocyst which develops after radical hysterectomy in cancer of the uterine cervix. J Jpn Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1955; 2:178–203.7. Metcalf KS, Peel KR. Lymphocele. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993; 75:387–392.8. Suzuki M, Ohwada M, Sato I. Pelvic lymphocysts following retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy: retroperitoneal partial “no-closure” for ovarian and endometrial cancers. J Surg Oncol. 1998; 68:149–152.9. Kim JK, Jeong YY, Kim YH, Kim YC, Kang HK, Choi HS. Postoperative pelvic lymphocele: treatment with simple percutaneous catheter drainage. Radiology. 1999; 212:390–394.10. Park NY, Seong WJ, Chong GO, Hong DG, Cho YL, Park IS, et al. The effect of nonperitonization and laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for minimizing the incidence of lymphocyst formation after radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010; 20:443–448.11. Achouri A, Huchon C, Bats AS, Bensaid C, Nos C, Lécuru F. Complications of lymphadenectomy for gynecologic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013; 39:81–86.12. Tam KF, Lam KW, Chan KK, Ngan HY. Natural history of pelvic lymphocysts as observed by ultrasonography after bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 32:87–90.13. Benedetti-Panici P, Maneschi F, Cutillo G, D’Andrea G, di Palumbo VS, Conte M, et al. A randomized study comparing retroperitoneal drainage with no drainage after lymphadenectomy in gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 1997; 65:478–482.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Risk factors of lymphocele after RAH with pelvic lymph node dissection for women with cervical cancer

- Infected Lymphocele Extending to the Leg after Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy and Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection

- Distribution of lymphocele following lymphadenectomy in patients with gynecological malignancies

- Clinical Implication of Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Metastasis in Rectal Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy

- Prevention of lymphocele development in gynecologic cancers by the electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing device