J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Sep;32(9):1522-1533. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1522.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics between Community-based and Hospital-based Suicidal Ideators and Its Implications for Tailoring Strategies for Suicide Prevention: Korean Cohort for the Model Predicting a Suicide and Suicide-related Behavior

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neuropsychiatry, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. aym@snu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Neuropsychiatry, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea.

- 4Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Wonkwang University, Iksan, Korea.

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea.

- 6Department of Psychiatry, Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan, Korea.

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 8Department of Neuropsychiatry, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea.

- 9Department of Psychiatry, Gachon University Gil Medical Center, Incheon, Korea.

- 10Department of Psychiatry, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- 11Deparmtent of Sociology, Seoul National University College of Social Sciences, Seoul, Korea.

- 12Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University College of Medicine, Suwon, Korea.

- 13Department of Psychology, Chungbuk National University College of Social Sciences, Cheongju, Korea.

- 14Department of Psychiatry, Depression Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2385961

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1522

Abstract

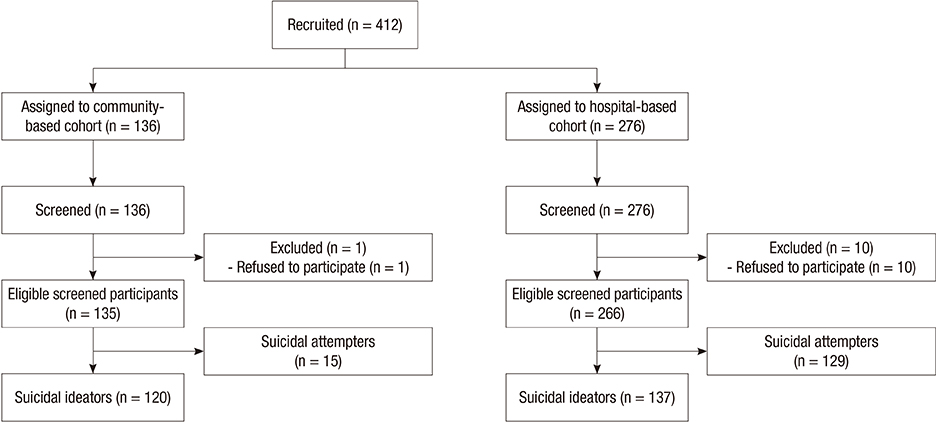

- In this cross-sectional study, we aimed to identify distinguishing factors between populations with suicidal ideation recruited from hospitals and communities to make an efficient allocation of limited anti-suicidal resources according to group differences. We analyzed the baseline data from 120 individuals in a community-based cohort (CC) and 137 individuals in a hospital-based cohort (HC) with suicidal ideation obtained from the Korean Cohort for the Model Predicting a Suicide and Suicide-related Behavior (K-COMPASS) study. First, their sociodemographic factors, histories of medical and psychiatric illnesses, and suicidal behaviors were compared. Second, diagnosis by the Korean version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, scores of psychometric scales were used to assess differences in clinical severity between the groups. The results revealed that the HC had more severe clinical features: more psychiatric diagnosis including current and recurrent major depressive episodes (odds ratio [OR], 4.054; P < 0.001 and OR, 11.432; P < 0.001, respectively), current suicide risk (OR, 4.817; P < 0.001), past manic episodes (OR, 9.500; P < 0.001), past hypomanic episodes (OR, 4.108; P = 0.008), current alcohol abuse (OR, 3.566; P = 0.020), and current mood disorder with psychotic features (OR, 20.342; P < 0.001) besides significantly higher scores in depression, anxiety, alcohol problems, impulsivity, and stress. By comparison, old age, single households, and low socioeconomic status were significantly associated with the CC. These findings indicate the necessity of more clinically oriented support for hospital visitors and more socioeconomic aid for community-dwellers with suicidality.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Self-Transcendence Mediates the Relationship between Early Trauma and Fatal Methods of Suicide Attempts

Jeong Hun Yang, Sang Jin Rhee, C. Hyung Keun Park, Min Ji Kim, Daun Shin, Jae Won Lee, Junghyun Kim, Hyeyoung Kim, Hyun Jeong Lee, Kyooseob Ha, Yong Min Ahn

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(5):e39. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e39.

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Suicide: fact sheet [Internet]. accessed on 4 May 2017. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en.2. Statistics Korea. Annual report on the cause of death statistics 2015 [Internet]. accessed on 4 May 2017. Available at http://kosis.kr/ups/ups_01List.jsp?pubcode=YD.3. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Health Statistics 2016. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development;2016.4. Kwon JW, Chun H, Cho SI. A closer look at the increase in suicide rates in South Korea from 1986–2005. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9:72.5. Miret M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Sanchez-Moreno J, Vieta E. Depressive disorders and suicide: epidemiology, risk factors, and burden. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013; 37:2372–2374.6. Salvador-Carulla L, Bendeck M, Fernández A, Alberti C, Sabes-Figuera R, Molina C, Knapp M. Costs of depression in Catalonia (Spain). J Affect Disord. 2011; 132:130–138.7. Valenstein M, Eisenberg D, McCarthy JF, Austin KL, Ganoczy D, Kim HM, Zivin K, Piette JD, Olfson M, Blow FC. Service implications of providing intensive monitoring during high-risk periods for suicide among VA patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009; 60:439–444.8. Knox KL, Litts DA, Talcott GW, Feig JC, Caine ED. Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US Air Force: cohort study. BMJ. 2003; 327:1376.9. Sareen J, Isaak C, Katz LY, Bolton J, Enns MW, Stein MB. Promising strategies for advancement in knowledge of suicide risk factors and prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2014; 47:S257–S263.10. Maniam T, Chinna K, Lim CH, Kadir AB, Nurashikin I, Salina AA, Mariapun J. Suicide prevention program for at-risk groups: pointers from an epidemiological study. Prev Med. 2013; 57:Suppl. S45–S46.11. Yoon TH, Noh M, Han J, Jung-Choi K, Khang YH. Deprivation and suicide mortality across 424 neighborhoods in Seoul, South Korea: a Bayesian spatial analysis. Int J Public Health. 2015; 60:969–976.12. Iemmi V, Bantjes J, Coast E, Channer K, Leone T, McDaid D, Palfreyman A, Stephens B, Lund C. Suicide and poverty in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016; 3:774–783.13. Lapierre S, Erlangsen A, Waern M, De Leo D, Oyama H, Scocco P, Gallo J, Szanto K, Conwell Y, Draper B, et al. A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis. 2011; 32(9):–. 88–98.14. Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, Namkoong K, Chae JH, Lee GC, Jeon SI, Min KJ, et al. Validity of Korean version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006; 2:50–55.15. An JY, Seo ER, Lim KH, Shin JH, Kim JB. Standardization of the Korean version of screening tool for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9). J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2013; 19:47–56.16. Yook SP, Kim JS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16:185–197.17. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;2001.18. Chang JW, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Yoon SJ, Jang HS. Validity of alcohol use disorder identification test-Korean revised version for screening alcohol use disorder according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition criteria. Korean J Fam Med. 2016; 37:323–328.19. Heo SY, Oh JY, Kim JH. The Korean version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, 11th version: its reliability and validity. Korean J Psychol Gen. 2012; 31:769–782.20. Jeon JR, Lee EH, Lee SW, Jeong EG, Kim JH, Lee D, Jeon HJ. The early trauma inventory self report-short form: psychometric properties of the Korean version. Psychiatry Investig. 2012; 9:229–235.21. Lee MA, Kim SH, Park JH, Sim EJ. Factors of suicidal ideation and behavior: social relationships and family. Korea J Popul Stud. 2010; 33:61–84.22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16:606–613.23. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011; 63:Suppl 11. S467–S472.24. Jeon HJ, Kang ES, Lee EH, Jeong EG, Jeon JR, Mischoulon D, Lee D. Childhood trauma and platelet brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) after a three month follow-up in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2012; 46:966–972.25. Roy A. Childhood trauma and impulsivity. Possible relevance to suicidal behavior. Arch Suicide Res. 2005; 9:147–151.26. Braquehais MD, Oquendo MA, Baca-García E, Sher L. Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Compr Psychiatry. 2010; 51:121–129.27. Park JE, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Sohn JH, Seong SJ, Suk HW, Cho MJ. Impact of stigma on use of mental health services by elderly Koreans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015; 50:757–766.28. Lanouette NM, Folsom DP, Sciolla A, Jeste DV. Psychotropic medication nonadherence among United States Latinos: a comprehensive literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009; 60:157–174.29. Statistics Korea. 2016 Korean social index [Internet]. accessed on 4 May 2017. Available at http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/6/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=359629.30. Merikangas KR. Divorce and assortative mating among depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1984; 141:74–76.31. Hooghe M, Vanhoutte B. An ecological study of community-level correlates of suicide mortality rates in the Flemish region of Belgium, 1996–2005. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011; 41:453–464.32. Kunst AE, van Hooijdonk C, Droomers M, Mackenbach JP. Community social capital and suicide mortality in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional registry-based study. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:969.33. Putnam RD, Leonardi R, Nanetti RY. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press;1993.34. Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, van Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, Carli V, Höschl C, Barzilay R, Balazs J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016; 3:646–659.35. Park JI, Oh KY, Chung YC. Psychiatry in Korea. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013; 6:186–190.36. Park CH, Yoo SH, Lee J, Cho SJ, Shin MS, Kim EY, Kim SH, Ham K, Ahn YM. Impact of acute alcohol consumption on lethality of suicide methods. Compr Psychiatry. 2017; 75:27–34.37. Zhang H, Neelarambam K, Schwenke TJ, Rhodes MN, Pittman DM, Kaslow NJ. Mediators of a culturally-sensitive intervention for suicidal African American women. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013; 20:401–414.38. Kuroki M. Suicide and unemployment in Japan: evidence from municipal level suicide rates and age-specific suicide rates. J Socio Econ. 2010; 39:683–691.39. Breuer C. Unemployment and suicide mortality: evidence from regional panel data in Europe. Health Econ. 2015; 24:936–950.40. Ministry of the Interior (KR). Resident registration population statistics [Internet]. accessed on 4 May 2017. Available at http://rcps.egov.go.kr:8081/jsp/stat/ppl_stat_jf.jsp.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Suicide prevention by education

- The Effect of Suicide Prevention Education on Attitudes Toward Suicide in Police Officers

- Association between Exposure to Suicide Events and Suicidal Ideation : Comparison Among Groups with Exposure to Suicidal Death, Non-Suicidal Death, and No Death

- A Qualitative Study of Psychological State of Suicide Victims through Suicide Notes

- Predictors of Suicide Attempt among Middle School Students with Suicidal Ideation: Analysis of Data from the 15th (2019) Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey