J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Sep;32(9):1401-1414. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1401.

Trends of Social Inequalities in the Specific Causes of Infant Mortality in a Nationwide Birth Cohort in Korea, 1995–2009

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, Kangwon National University, School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea.

- 2Department of Statistics, Kangwon National University, College of Natural Science, Chuncheon, Korea. ykim7stat@kangwon.ac.kr

- KMID: 2385945

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.9.1401

Abstract

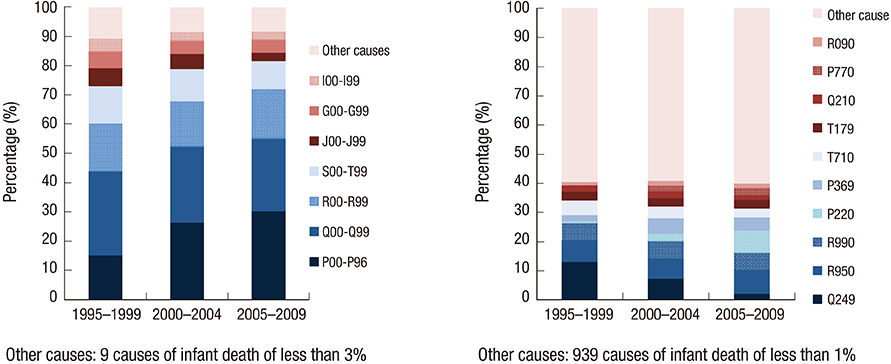

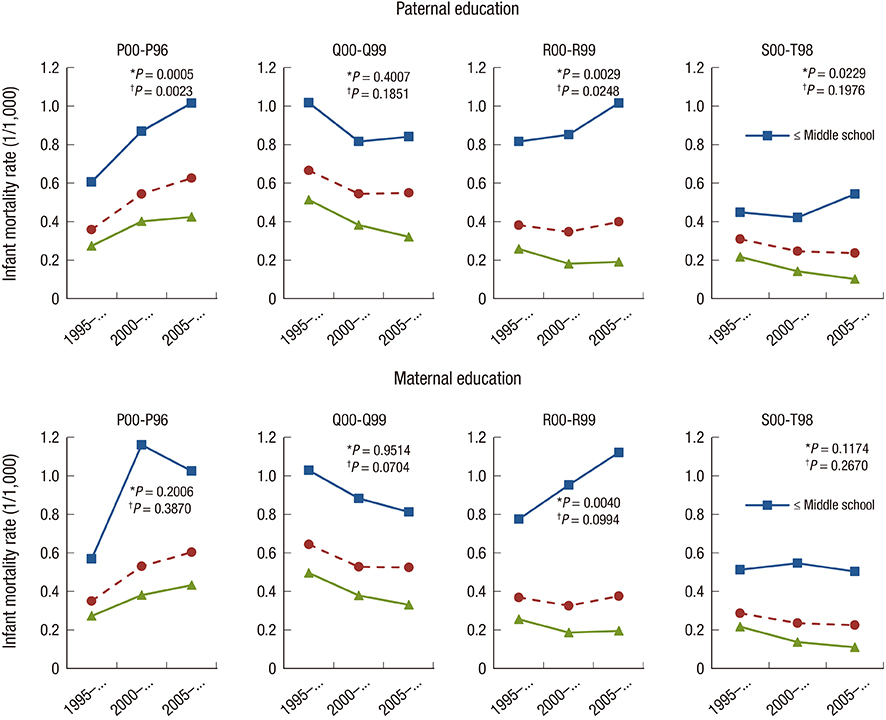

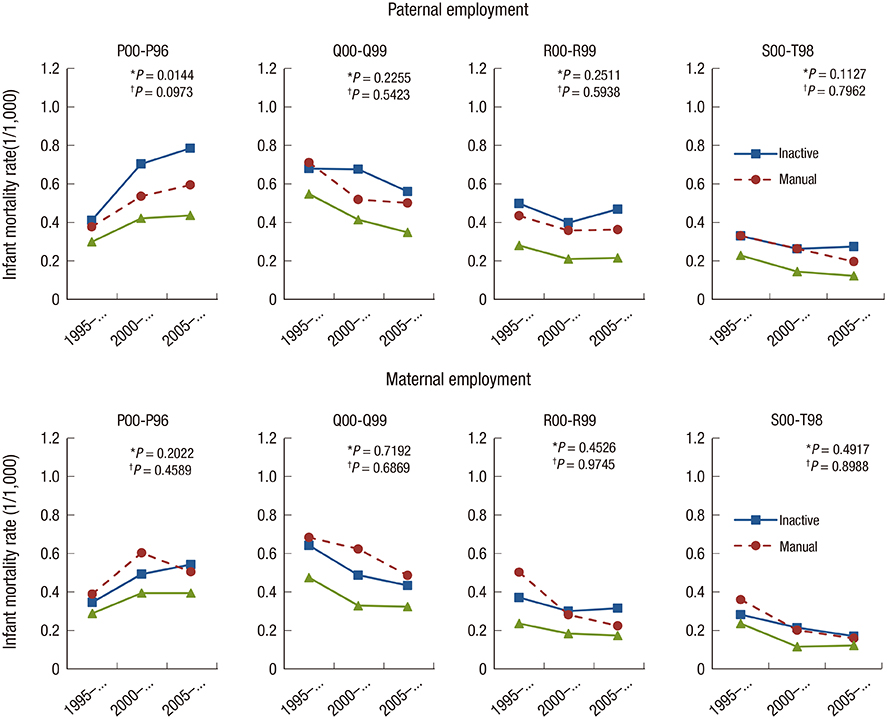

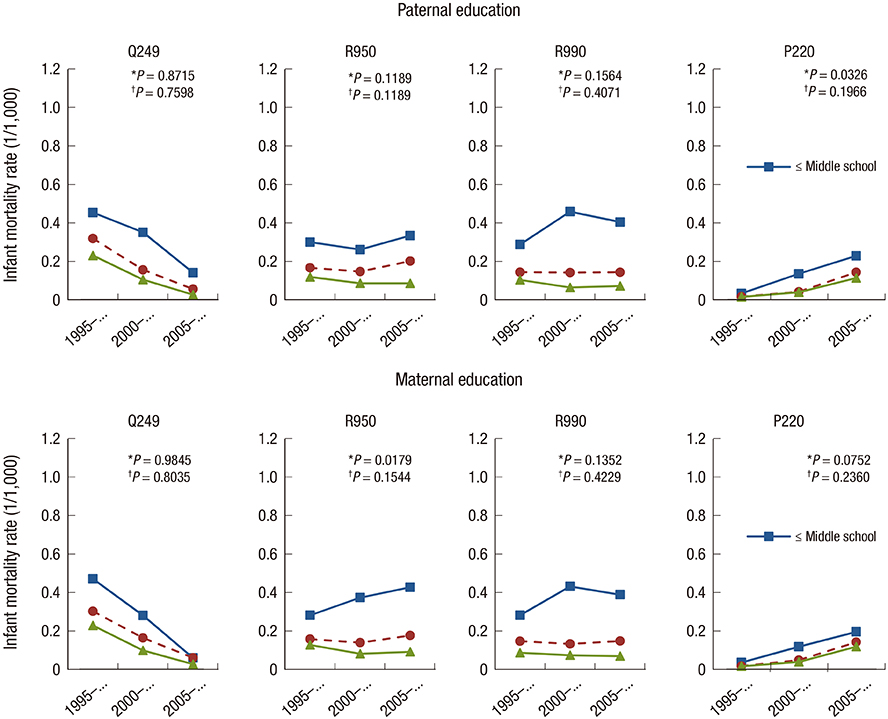

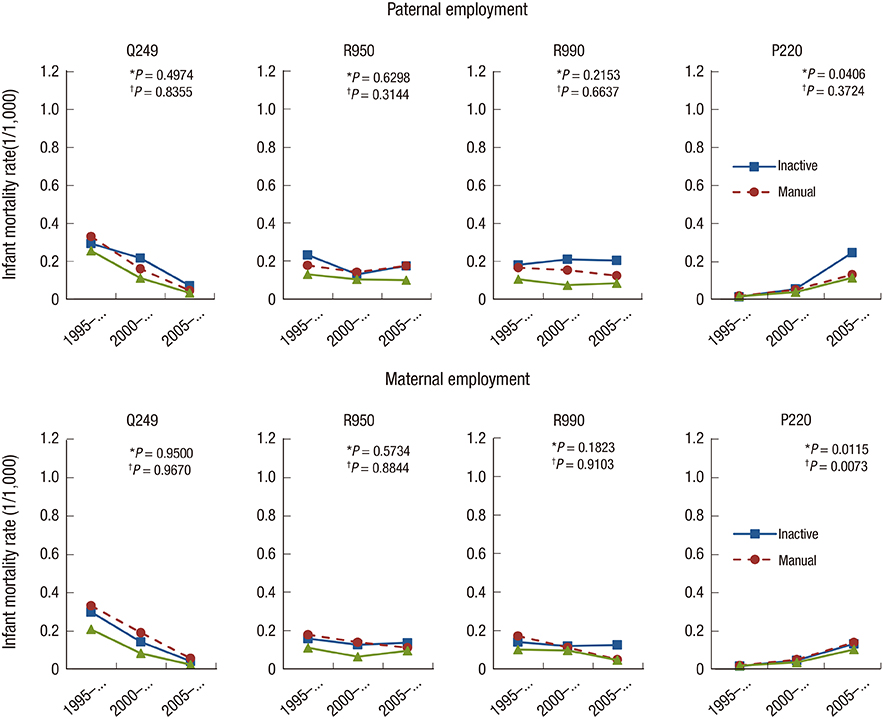

- The relationship between social disparity and specific causes of infant mortality has rarely been studied. The present study analyzed infant mortality trends according to the causes of death and the inequalities in specific causes of infant mortality between different parental social classes. We analyzed 8,209,836 births from the Statistics Korea between 1995 and 2009. The trends of disparity for cause-specific infant mortality according to parental education and employment were examined using the Cox proportional hazard model for the birth-year intervals of 1995-1999, 2000-2004, and 2005-2009. Adjusted hazard ratios were calculated after adjusting for infants' gender, parents' age, maternal obstetrical history, gestational age, and birth weight. An increasing trend in social inequalities in all-cause infant mortality according to paternal education was evident. Social inequalities in infant mortality were greater for "Not classified symptoms, signs and findings" (International Classification of Diseases 10th revision [ICD-10]: R00-R99) and "Injury, poisoning and of external causes" (S00-T98), particularly for "Ill-defined and unspecified causes" (R990) and "Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)" (R950); and increased overtime for "Not classified symptoms, signs and findings" (R00-R99), "Injury, poisoning and of external causes" (S00-T98) and "Conditions in perinatal period" (P00-P96), particularly for "SIDS" (R950) and "Respiratory distress syndrome of newborns (RDS)" (P220). The specific causes of infant mortality, in particular the "Not classified causes" (R00-R99 coded deaths) should be investigated more thoroughly to reduce inequality in health.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Jørgensen T, Mortensen LH, Andersen AM. Social inequality in fetal and perinatal mortality in the Nordic countries. Scand J Public Health. 2008; 36:635–649.2. Weightman AL, Morgan HE, Shepherd MA, Kitcher H, Roberts C, Dunstan FD. Social inequality and infant health in the UK: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:e000964.3. Kim D, Saada A. The social determinants of infant mortality and birth outcomes in Western developed nations: a cross-country systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013; 10:2296–2335.4. Ko YJ, Shin SH, Park SM, Kim HS, Lee JY, Kim KH, Cho B. Effects of employment and education on preterm and full-term infant mortality in Korea. Public Health. 2014; 128:254–261.5. Statistics Korea. Supplement Survey for Specific Causes of Death in 2009–2011 in Korea. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;2012.6. Han YJ, Choi JS, Lee SW, Seo K, Oh HC, Lee SW, Lee NH, Shin CW. The Level and Characteristics of Under 5 Years Old Mortality. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2009.7. Choi JS, Seo K, Lee NH, Kim SY, Lee SW, Lee SW, Boo YK. Infant and Maternal Mortality Survey in 2007??008: Maternal Death. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2010.8. Choi JS. Infant mortality and unknown cause of death. Health Welf Issue Focus. 2014; 216:1–8.9. Nordström ML, Cnattingius S, Haglund B. Social differences in Swedish infant mortality by cause of death, 1983 to 1986. Am J Public Health. 1993; 83:26–30.10. Bambang S, Spencer NJ, Logan S, Gill L. Cause-specific perinatal death rates, birth weight and deprivation in the West Midlands, 1991–93. Child Care Health Dev. 2000; 26:73–82.11. Arntzen A, Samuelsen SO, Daltveit AK, Stoltenberg C. Post-neonatal mortality in Norway 1969–95: a cause-specific analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2006; 35:1083–1089.12. El-Sayed AM, Finkton DW Jr, Paczkowski M, Keyes KM, Galea S. Socioeconomic position, health behaviors, and racial disparities in cause-specific infant mortality in Michigan, USA. Prev Med. 2015; 76:8–13.13. Jung UC. Status and Policy Direction of the Housing Welfare. Seoul: Korea Development Institute;2012.14. Spencer N, Logan S. Sudden unexpected death in infancy and socioeconomic status: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004; 58:366–373.15. Spiers PS, Guntheroth WG. The effect of the weekend on the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1999; 104:e58.16. Unger B, Kemp JS, Wilkins D, Psara R, Ledbetter T, Graham M, Case M, Thach BT. Racial disparity and modifiable risk factors among infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Pediatrics. 2003; 111:E127–31.17. Kraus JF, Greenland S, Bulterys M. Risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome in the US Collaborative Perinatal Project. Int J Epidemiol. 1989; 18:113–120.18. Byrd DR, Katcher ML, Peppard P, Durkin M, Remington PL. Infant mortality: explaining black/white disparities in Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2007; 11:319–326.19. Hauck FR, Moore CM, Herman SM, Donovan M, Kalelkar M, Christoffel KK, Hoffman HJ, Rowley D. The contribution of prone sleeping position to the racial disparity in sudden infant death syndrome: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics. 2002; 110:772–780.20. Wise PH. The anatomy of a disparity in infant mortality. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003; 24:341–362.21. Van Nguyen JM, Abenhaim HA. Sudden infant death syndrome: review for the obstetric care provider. Am J Perinatol. 2013; 30:703–714.22. Wasilewska J, Kaczmarski M. Modifiable risk factors of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The current guidelines for reducing the risk of SIDS. Wiad Lek. 2009; 62:30–36.23. de Jonge GA, Hoogenboezem J. Epidemiology of 25 years of crib death (sudden infant death syndrome) in the Netherlands; incidence of crib death and prevalence of risk factors in 1980–2004. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005; 149:1273–1278.24. Yoo SH, Kim AJ, Kang SM, Lee HY, Seo JS, Kwon TJ, Yang KM. Sudden infant death syndrome in Korea: a retrospective analysis of autopsy-diagnosed cases. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:438–442.25. British Columbia Reproductive Care Program (CA). Newborn Guideline 6: Surfactant Replacement Therapy in Neonates. Vancouver: British Columbia Reproductive Care Program;1993.26. Halliday H. Surfactant therapy: questions and answers. J Neonatal Nurs. 1997; 3:28–34.27. Malloy MH, Freeman DH. Respiratory distress syndrome mortality in the United States, 1987 to 1995. J Perinatol. 2000; 20:414–420.28. Frisbie WP, Song SE, Powers DA, Street JA. The increasing racial disparity in infant mortality: respiratory distress syndrome and other causes. Demography. 2004; 41:773–800.29. Park MJ, Son M, Kim YJ, Paek D. Social inequality in birth outcomes in Korea, 1995–2008. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28:25–35.30. Lee TJ, Kim DS, Shin DH. A clinical study of the acute respiratory distress syndrome in children. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2003; 46:42–50.31. Son M, Oh J, Choi YJ, Kong JO, Choi J, Jin E, Jung ST, Park SJ. The effects of the parents’ social class on infant and child death among 1995–2004 birth cohort in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006; 39:469–476.32. Yun JW, Kim YJ, Son M. Regional deprivation index and socioeconomic inequalities related to infant deaths in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31:568–578.33. Hong J, Lee B, Ha EH, Park H. Parental socioeconomic status and unintentional injury deaths in early childhood: consideration of injury mechanisms, age at death, and gender. Accid Anal Prev. 2010; 42:313–319.34. Jung SE. The characteristics of childhood injuries compared to adult injuries. J Korean Med Assoc. 2008; 51:214–218.35. Plasència A, Borrell C. Reducing socioeconomic inequalities in road traffic injuries: time for a policy agenda. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001; 55:853–854.36. Hyder AA, Peden M. Inequality and road-traffic injuries: call for action. Lancet. 2003; 362:2034–2035.37. Huang MI, O’Riordan MA, Fitzenrider E, McDavid L, Cohen AR, Robinson S. Increased incidence of nonaccidental head trauma in infants associated with the economic recession. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011; 8:171–176.38. Barros TL, Dias MJ, Nina RV. Congenital cardiac disease in childhood x socioeconomic conditions: a relationship to be considered in public health? Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2014; 29:448–454.39. Han YJ, Lee SW, Jang YS, Kim DJ, Lee SW. Infant and Perinatal Mortality Rates of Korea in 1999. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2002.40. Choi JS, Seo K, Lee NH, Lee SW, Lee SW, Shin CW, Boo YK. Infant and Maternal Mortality Survey in 2007??008: Infant Death and Stillbirth. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2010.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Role of Parental Social Class in Preterm Births and Low Birth Weight in Association with Child Mortality:A National Retrospective Cohort Study in Korea

- The Effects of the Parents' Social Class on Infant and Child Death among 1995-2004 Birth Cohort in Korea

- Socioeconomic inequalities in health status in Korea

- Widening Social Inequalities in Cancer Mortality of Children Under 5 Years in Korea

- Recent Trends in Neonatal Mortality in Very Low Birth Weight Korean Infants: In Comparison with Japan and the USA