J Korean Soc Spine Surg.

2017 Jun;24(2):65-71. 10.4184/jkss.2017.24.2.65.

Changes in Perceptions of Narcotic Analgesic Treatment and Quality of Life in Chronic Back Pain Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kwangju Christian Hospital, Gwangju, Korea. bakter@daum.net

- KMID: 2385641

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4184/jkss.2017.24.2.65

Abstract

- STUDY DESIGN: Prospective study.

OBJECTIVES

This study was conducted to investigate changes in perceptions of treatment using narcotic analgesics and quality of life in chronic back pain patients. SUMMARY OF LITERATURE REVIEW: Negative perceptions of narcotic analgesics as pain killers have been established as factors affecting compliance and adherence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

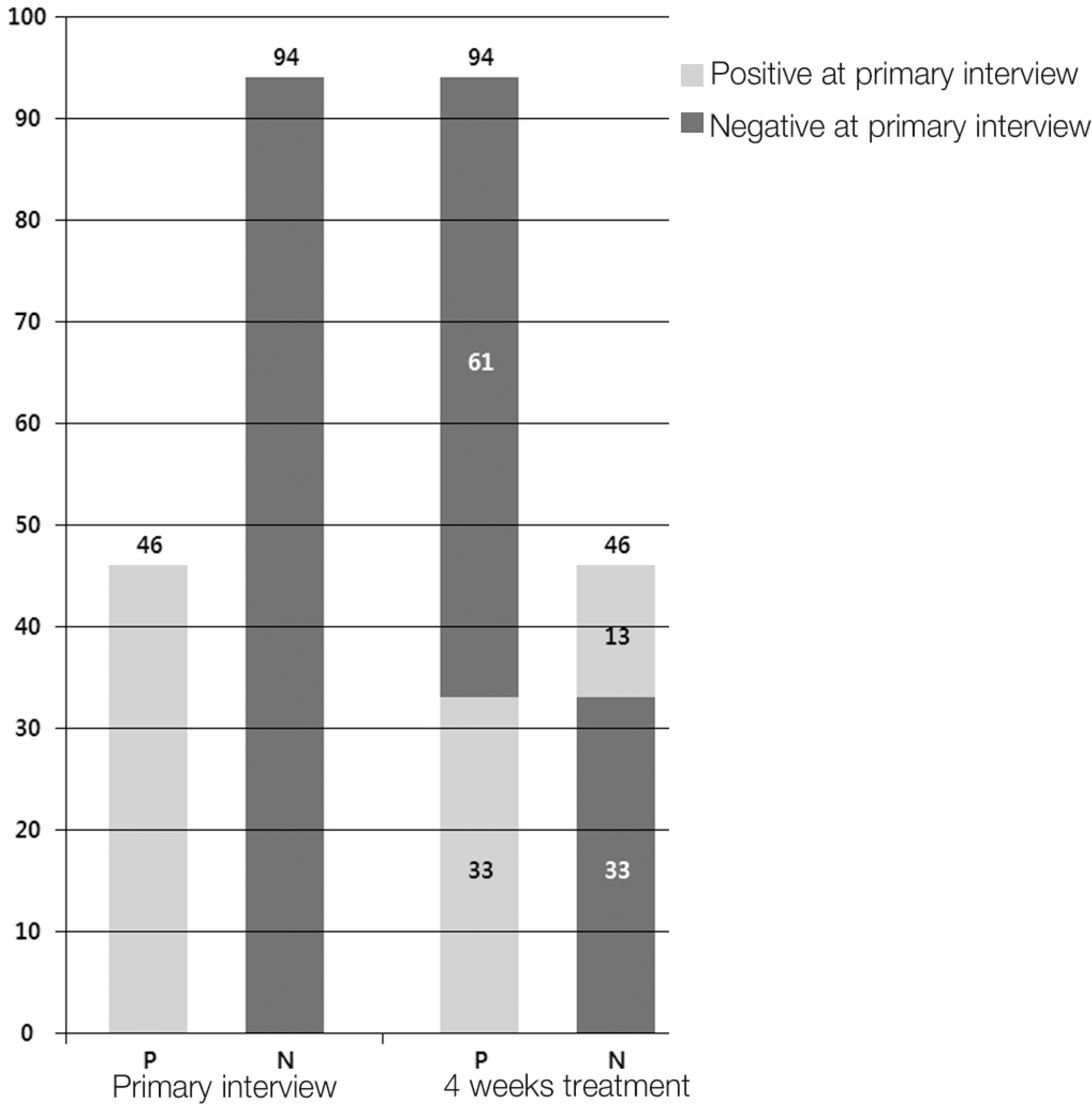

A total of 140 patients who had chronic back pain for over 3 months were examined using clinical scales such as the Korean version of the Oswestry Disability Index (KODI), the Short Form-12 (SF-12), and a visual analog scale (VAS). The survey regarding narcotic analgesics classified patients as having positive perceptions if they reported absolutely not wanting to use them or being unlikely to use them at the primary interview and after 4 weeks of treatment.

RESULTS

Ninety-four patients (68%) reported negative perceptions of narcotic analgesics at the primary interview. Sixty-one of those patients (64%) changed their perceptions, reporting positive perceptions after 4 weeks of treatment, as indicated by the ODI (p=0.01), SF-12 (p=0.01), and VAS (p=0.01) scores. A change from positive to negative perceptions after 4 weeks of treatment was observed in 13 patients (28%) who experienced adverse effects of narcotics treatment (p=0.01). Among the 33 patients (23%) whose negative perceptions did not change, dissatisfaction with previous treatment was found to be a contributing factor in 22 (66%).

CONCLUSIONS

Clinical improvements after treatment using narcotic analgesics in chronic back pain patients resulted in a significant positive impact on perceptions about narcotic analgesics. Narcotic analgesics could be an alternative treatment choice in chronic back pain patients because of improvements in their quality of life.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Von Korff M, Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996; 21:2833–7.

Article2. Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999; 354:581–5.

Article3. Turk DC, Okifuji A. Pain terms and Taxonomies of pain. (in. Ballantyne JC, Fishman SM, Rathmell JP, editors. Bonica's Management of Pain. 4 th ed.Philadelphia, Lippincott: Wil-liams & Wilkins;2009. p. 13–23. ).4. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:478–91.

Article5. Tennant FS J, Uelmen GF. Narcotic maintenance for chronic pain: medical and legal guidelines. Postgrad Med. 1983; 73:81–3.6. Zenz M, Strumpf M, Tryba M. Longterm opioid therapy in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992; 7:69–77.7. Spinhoven P, TerKulie M, Kole-snijders AMJ, et al. Cata-strophizing and internal pain control as mediators of outcome in the multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain. Eur J pain. 2004; 8:211–9.

Article8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Low back pain in adults: early management. Clinical guideline CG88[Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;2009. May [updated 2016 Nov] Available from:. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88/resources/low-back-pain-inadults-early-manage-ment-975695607493.9. Martell BA, O'connor PG, kerns RD, et al. Systemic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann intern med. 2007; 146:116–27.10. Caudaill-slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescription for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs 2000. Pain. 2004; 109:514–9.11. Duthey B, Scholten W. Adequacy of opioid analgesic con-sumption at country, global, and regional levels in 2010, its relationship with development level, and changes compared with 2006. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014; 47:283–97.

Article12. Ruoff GE, Rosenthal N, Jordan D, et al. Tramadol/acet-aminophen combination tablets for the treatment of chronic lower back pain: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled outpatient study. ClinTher. 2003; 25:1123–41.

Article13. Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999; 354:581–5.

Article14. YS Choi, DJ Kim, KY Lee, et al. How does chronic back pain influence quality of life in koreans: A cross-sectional study. Asian Spine J. 2014; 8:346–52.

Article15. Oliver JW, Kravitz R, Kaplan SH, et al. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:2206–12.

Article16. Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid Complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008; 11(Sup pl):105–20.

Article17. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006; 10:287–333.

Article18. Meyer-Rosberg K, Kvarnstrom A, Kinnman E, et al. Peripheral neuropathic pain-a multidimensional burden for patients. Eur J Pain. 2001; 5:379.

Article19. Moulin DE, Iezzi A, Amireh R, et al. Randomised trial of oral morphine for chronic noncancer pain. Lancet. 1996; 347:143–7.

Article20. Minozzi S, Amato L, Davoli M. Development of depen-dence following treatment with opioid analgesics for pain relief: a systematic review. Addiction. 2013; 108:688–98.

Article21. McNicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2003; 4:231–56.

Article22. Stone P, Minton O. European palliative care research col-laborative pain guidelines. Central side-effects management: what is the evidence to support best practice in the management of sedation, cognitive impairment and myoclonus. Palliat Med. 2011; 25:431–41.

Article23. Holzer P, Ahmedzai SH, Niederle N, et al. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction in cancer-related pain: causes, conse-quences, and a novel approach for its management. J Opioid Manag. 2009; 5:145–51.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analgesics for Lower Back Pain

- Use of the Complementary and Alternative Therapies, Pain and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Back Pain

- Acceptance versus catastrophizing in predicting quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain

- Common Analgesic Agents and Their Roles in Analgesic Nephropathy: A Commentary on the Evidence

- The Determinants of the Quality of Life and Pain of Back Pain Patients