Korean J Sports Med.

2017 Jun;35(1):40-47. 10.5763/kjsm.2017.35.1.40.

Comparison of Physical Activity and Health-related Quality of Life in Adolescents with and without Congenital Heart Disease: A Propensity Matched Comparison

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Sport Science, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea. syjae@uos.ac.kr

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Sejong General Hospital, Bucheon, Korea.

- 3College of Nursing, Korea University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2382042

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5763/kjsm.2017.35.1.40

Abstract

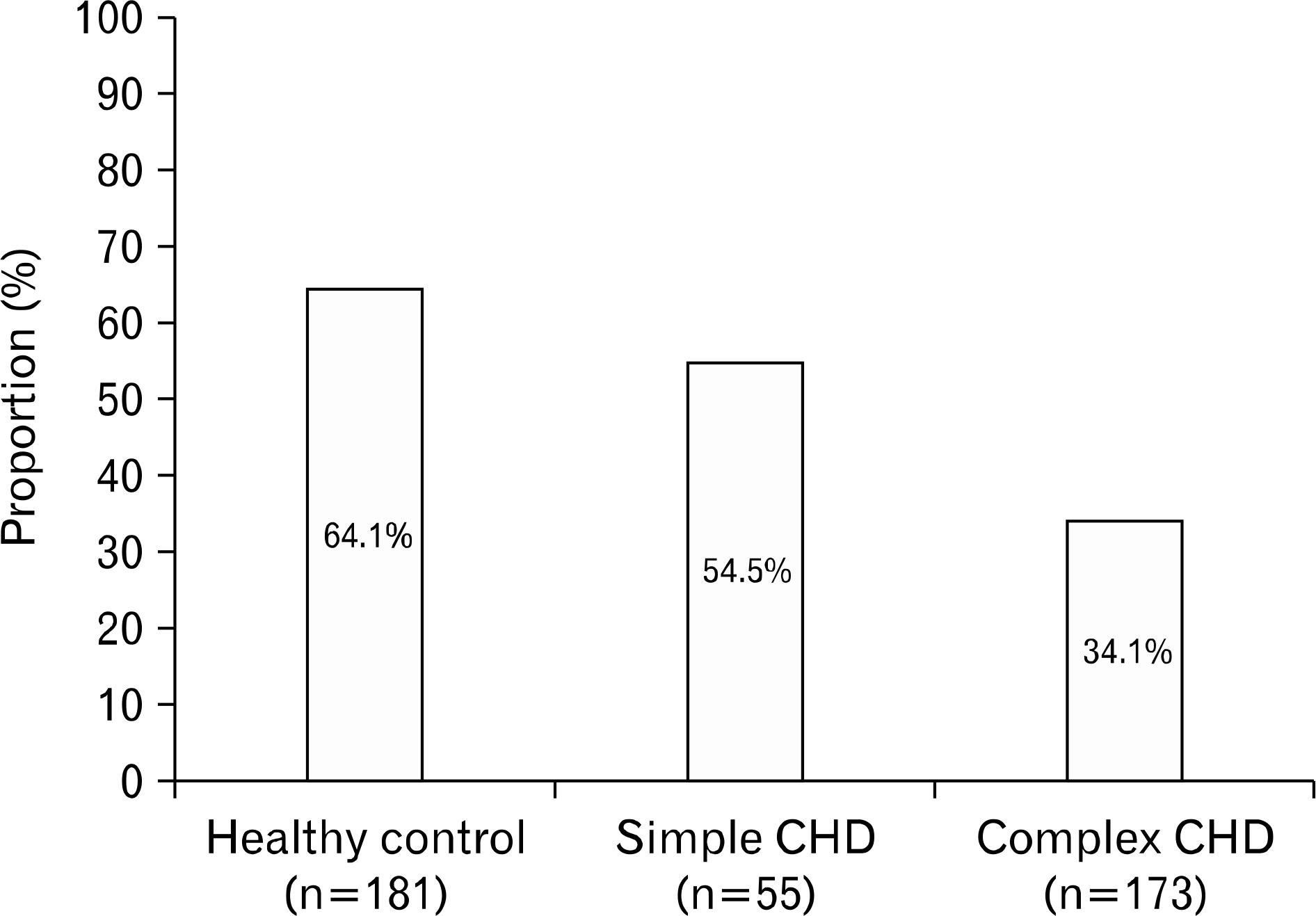

- Physical activity and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are associated with overall health outcomes in adolescents with congenital heart disease (CHD). The purpose of this study was to compare the levels of physical activity and HRQOL in adolescents with CHD and healthy controls. In addition, we compared these variables using a propensity score matching to reduce the confounding effects. Participants were divided into three groups with simple CHD (n=55), complex CHD (n=173), and healthy controls (n=181). Self-reported physical activity levels (metabolic equivalent of task [MET]-hr/wk) were obtained using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. HRQOL was evaluated using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory questionnaire. Total scores of HRQOL in adolescents with complex CHD were significantly lower than those with simple CHD (p=0.022) and healthy controls (p<0.001), respectively; however, there was no significant difference in total scores of HRQOL between adolescents with simple CHD and healthy controls. Levels of physical activity in adolescents with complex CHD were significantly lower than those with simple CHD (p=0.001) and healthy controls (p<0.001). After propensity matched analysis (44 pairs), the results were consistent with the above results. In conclusion, HRQOL scores and physical activity levels are significantly lower in adolescents with complex CHD, but not in adolescents with simple CHD, than in healthy adolescents.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

A Comparison of Physical Activity and Exercise Capacity in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease and Healthy Controls

Hyun Jeong Kim, Ja Kyoung Yoon, Seong-Ho Kim, Sae Young Jae

Korean J Sports Med. 2020;38(4):225-233. doi: 10.5763/kjsm.2020.38.4.225.

Reference

-

References

1. Amorim LF, Pires CA, Lana AM, et al. Presentation of congenital heart disease diagnosed at birth: analysis of 29,770 newborn infants. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2008; 84:83–90.

Article2. Eagleson KJ, Justo RN, Ware RS, Johnson SG, Boyle FM. Health-related quality of life and congenital heart disease in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013; 49:856–64.

Article3. Pemberton VL, McCrindle BW, Barkin S, et al. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Working Group on obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2010; 121:1153–9.

Article4. Fredriksen PM, Ingjer E, Thaulow E. Physical activity in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease: aspects of measurements with an activity monitor. Cardiol Young. 2000; 10:98–106.

Article5. Schickendantz S, Sticker EJ, Dordel S, Bjarnason-Wehrens B. Sport and physical activity in children with congenital heart disease. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007; 104:494.6. Blok IM, van Riel AC, Schuuring MJ, et al. Decrease in quality of life predicts mortality in adult patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension due to congenital heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2015; 23:278–84.

Article7. Uzark K, Jones K, Slusher J, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Quality of life in children with heart disease as perceived by children and parents. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:e1060–7.

Article8. Ekman-Joelsson BM, Berntsson L, Sunnegardh J. Quality of life in children with pulmonary atresia and intact ventricular septum. Cardiol Young. 2004; 14:615–21.

Article9. Kwon EN, Mussatto K, Simpson PM, Brosig C, Nugent M, Samyn MM. Children and adolescents with repaired tetralogy of fallot report quality of life similar to healthy peers. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011; 6:18–27.

Article10. Lunt D, Briffa T, Briffa NK, Ramsay J. Physical activity levels of adolescents with congenital heart disease. Aust J Physiother. 2003; 49:43–50.

Article11. McCrindle BW, Williams RV, Mital S, et al. Physical activity levels in children and adolescents are reduced after the Fontan procedure, independent of exercise capacity, and are associated with lower perceived general health. Arch Dis Child. 2007; 92:509–14.

Article12. McCrindle BW, Zak V, Sleeper LA, Paridon SM, Colan SD, Geva T, et al. Laboratory measures of exercise capacity and ventricular characteristics and function are weakly associated with functional health status after Fontan procedure. Circulation. 2010; 121:34–42.

Article13. Warnes CA, Liberthson R, Danielson GK, et al. Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37:1170–5.

Article14. Claessens P, Moons P, de Casterle BD, Cannaerts N, Budts W, Gewillig M. What does it mean to live with a congenital heart disease? A qualitative study on the lived experiences of adult patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005; 4:3–10.

Article15. Lin CY, Tsai FC, Chen YC, et al. Correlation of preoperative renal insufficiency with mortality and morbidity after aortic valve replacement: a propensity score matching analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95:e2576.16. Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world health organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. 2006; 14:66–70.

Article17. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001; 39:800–12.

Article18. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010.19. Dean PN, Gillespie CW, Greene EA, et al. Sports participation and quality of life in adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2015; 10:169–79.

Article20. Longmuir PE, McCrindle BW. Physical activity restrictions for children after the Fontan operation: disagreement between parent, cardiologist, and medical record reports. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:853–9.

Article21. Moola F, McCrindle BW, Longmuir PE. Physical activity participation in youth with surgically corrected congenital heart disease: devising guidelines so Johnny can participate. Paediatr Child Health. 2009; 14:167–70.

Article22. Salzer-Muhar U, Herle M, Floquet P, et al. Self-concept in male and female adolescents with congenital heart disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2002; 41:17–24.

Article23. Tahirovic E, Begic H, Tahirovic H, Varni JW. Quality of life in children after cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. Coll Antropol. 2011; 35:1285–90.24. Takken T, Giardini A, Reybrouck T, et al. Recommendations for physical activity, recreation sport, and exercise training in paediatric patients with congenital heart disease: a report from the Exercise, Basic & Translational Research Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, the European Congenital Heart and Lung Exercise Group, and the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012; 19:1034–65.25. Uzark K, Zak V, Shrader P, et al. Assessment of quality of life in young patients with single ventricle after the Fontan operation. J Pediatr. 2016; 170:166–72.e1.26. Knowles RL, Day T, Wade A, et al. Patient-reported quality of life outcomes for children with serious congenital heart defects. Arch Dis Child. 2014; 99:413–9.

Article27. Lee S, Kim SS. The life of adolescent patients with complex congenital heart disease. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010; 40:411–22.

Article28. Mueller GC, Sarikouch S, Beerbaum P, et al. Health-related quality of life compared with cardiopulmonary exercise testing at the midterm follow-up visit after tetralogy of Fallot repair: a study of the German competence network for congenital heart defects. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013; 34:1081–7.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Lifestyle and Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Propensity-Matched Comparison with a Healthy Control Group

- Factors Influencing Physical Activity in Adolescents with Complex Congenital Heart Disease

- Mediating Effect of Physical Activity in the Relationship between Depressive Symptoms and Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: The 2016 Nationwide Community Health Survey in Korea

- The comparison of health-related quality of life between the institutional elderly and the community living elderly

- Sexual health and sexual activity in the elderly