J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2017 May;58(5):563-571. 10.3341/jkos.2017.58.5.563.

Long-term Changes in Refractive Error after Spectacle Use

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. scheye@schmc.ac.kr

- KMID: 2378627

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2017.58.5.563

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To evaluate the long-term changes in spherical equivalent (SE) refractive error and astigmatism in patients after spectacle use.

METHODS

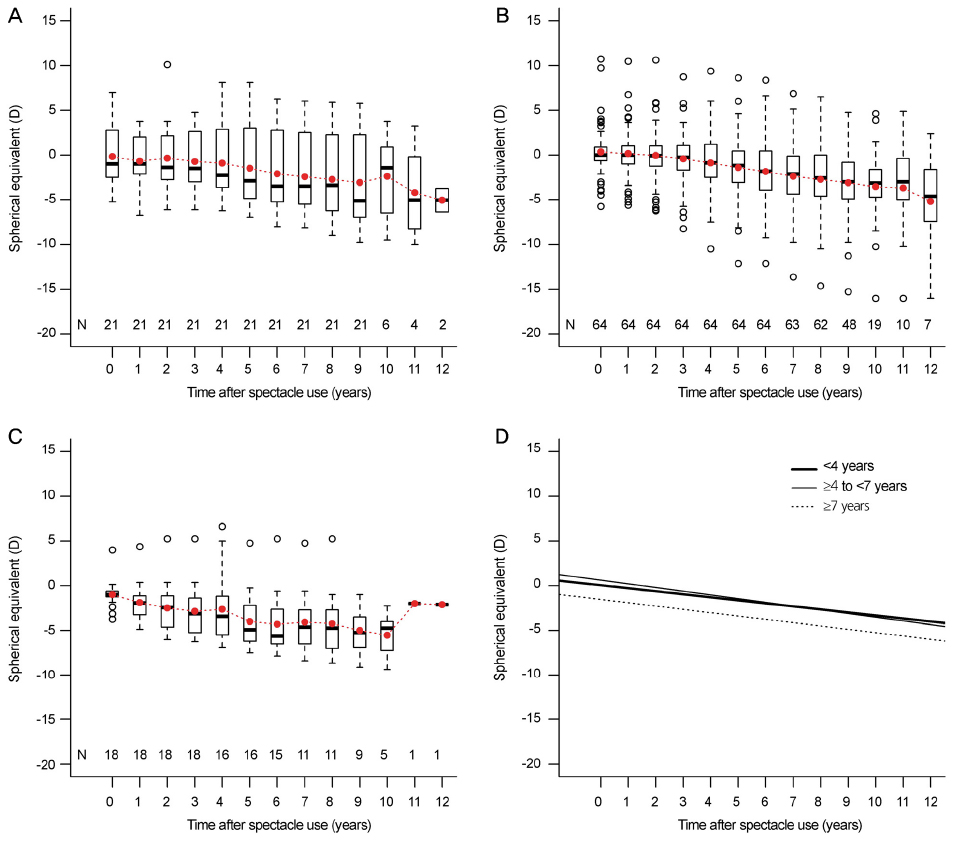

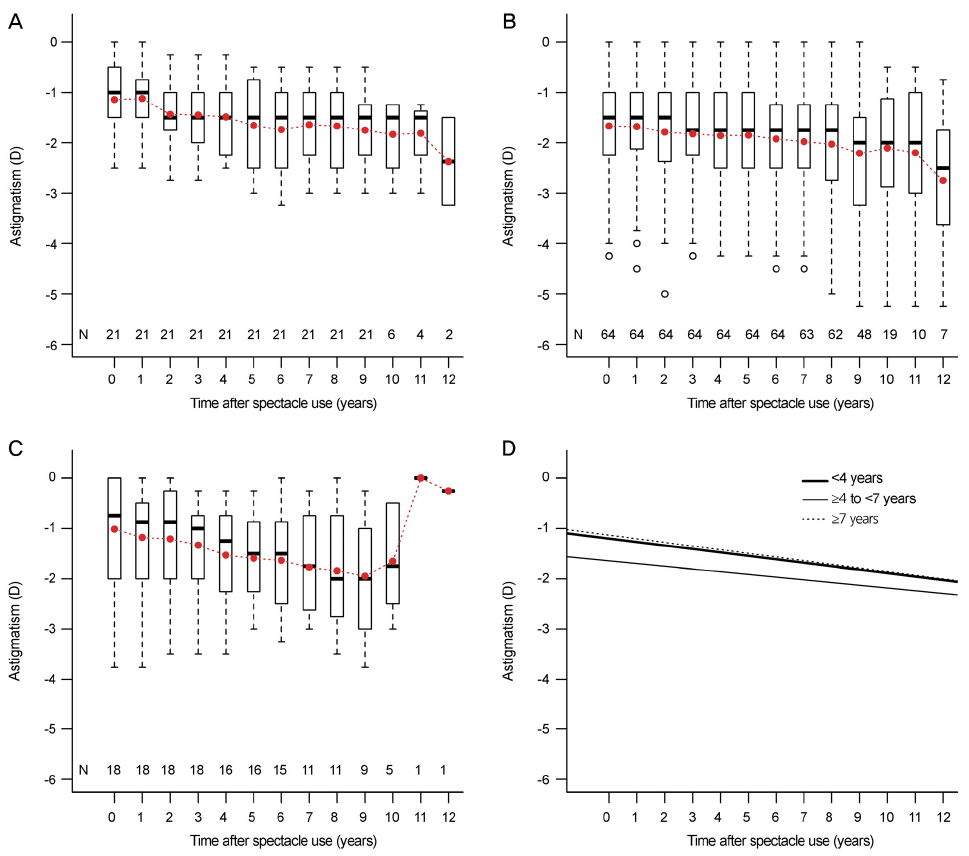

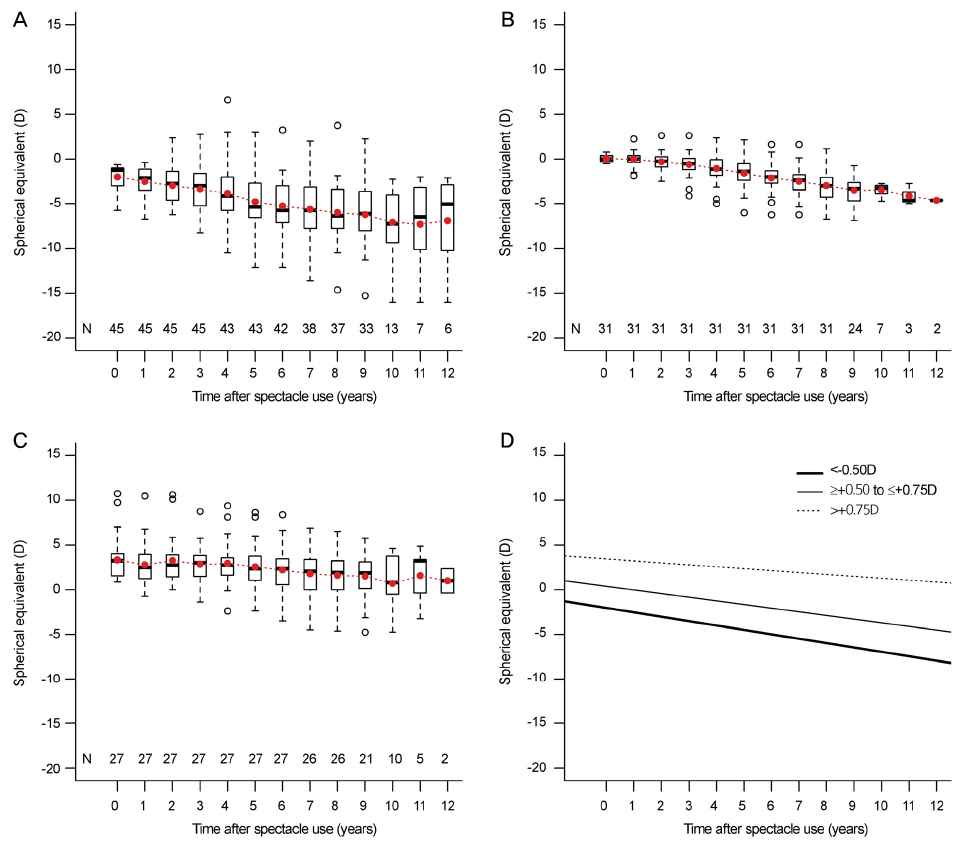

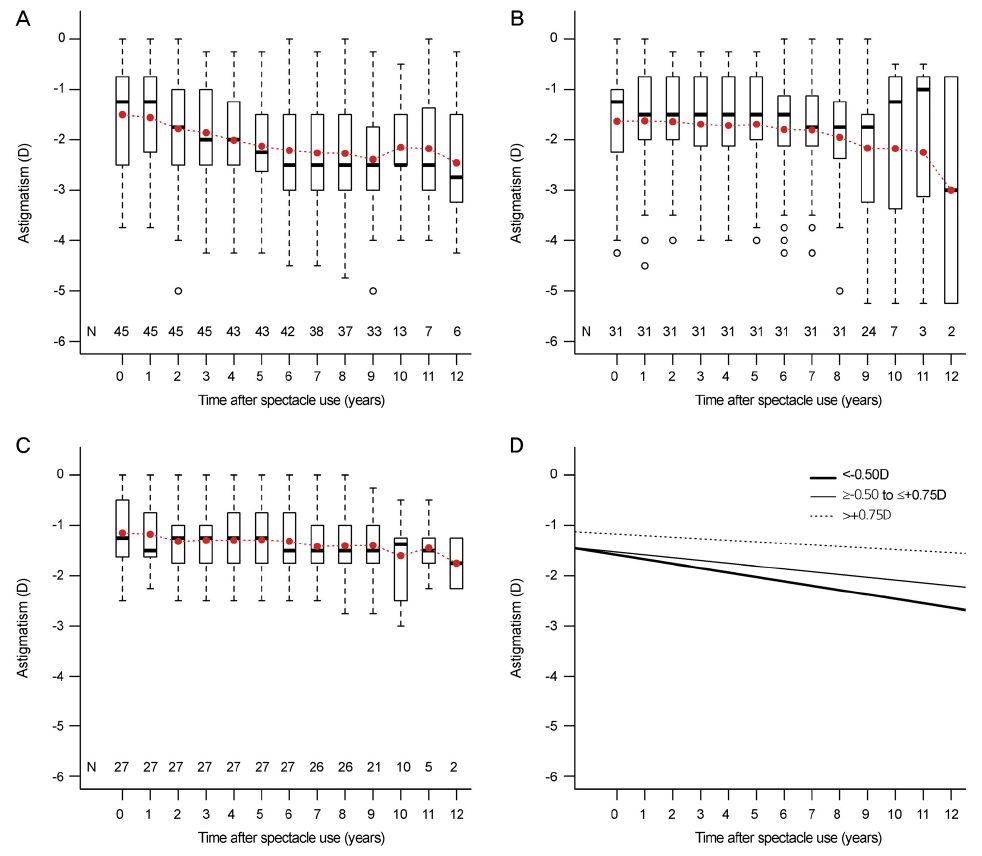

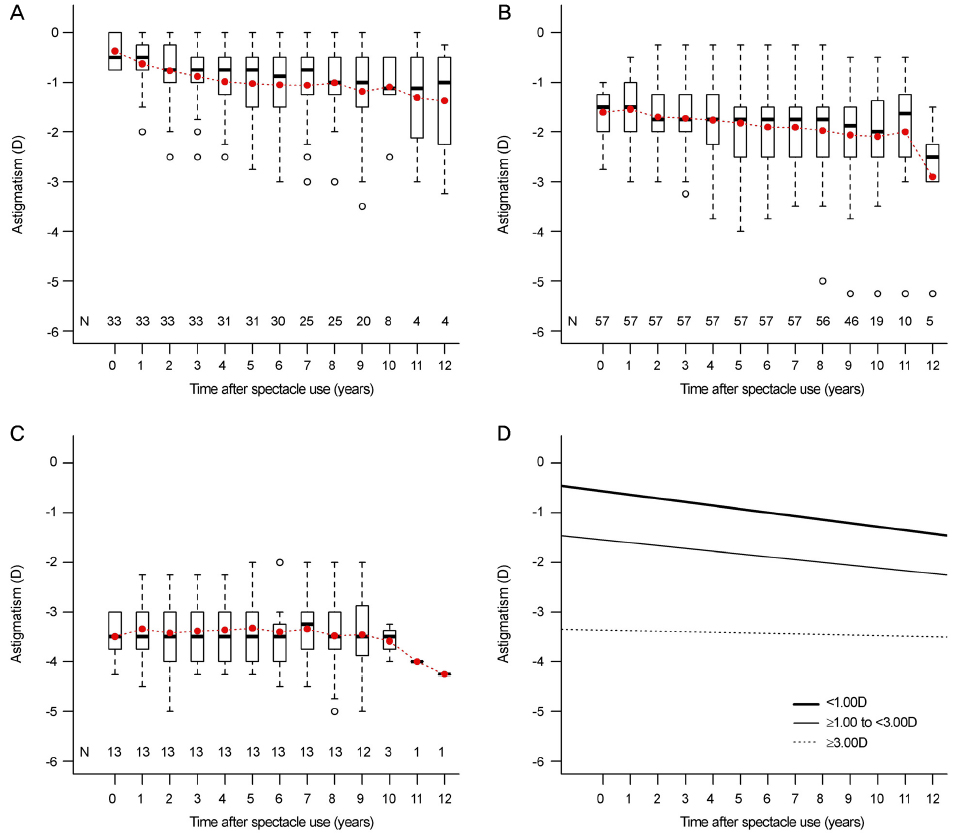

A total of 103 patients with refractive error without strabismus and amblyopia who received at least 3 years of follow-up after using spectacles were included in this study. Patients were divided into groups according to the age at which spectacles were used (<4 years, ≥4 to <7 years, ≥7 years), the initial degree of SE refractive error (<−0.50 diopter [D], −0.50 to +0.75 D, >+0.75 D), and the initial degree of astigmatism (<1.00 D, 1.00 to 3.00 D, ≥ 3.00 D). Changes in the SE refractive error and astigmatism were compared between these groups using mixed linear models..

RESULTS

Patients were followed up for a mean of 9.1 ± 1.6 years. An overall negative shift in SE refractive error and an increasing tendency in astigmatism during follow-up were noted regardless of the age at which spectacles were used (p < 0.001). The myopic group showed the largest negative shift in SE and the largest increase in astigmatism (p < 0.001, p = 0.02 respectively). The low and moderate astigmatism groups were more likely to have significant increases in astigmatism (p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with refractive error showed a negative shift in SE and an increasing tendency in astigmatism regardless of the age at which spectacles were used. Changes in SE and astigmatism may be influenced by the initial degree of SE, and the initial degree of astigmatism may influence changes in astigmatism.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hoyt C, Taylor D. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders;2013. chap. 4.2. Fan DS, Lam DS, Lam RF, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and progression of myopia of school children in Hong Kong. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45:1071–1075.3. Zhao J, Mao J, Luo R, et al. The progression of refractive error in school-age children: Shunyi district, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 134:735–743.4. Atkinson J, Anker S, Bobier W, et al. Normal emmetropization in infants with spectacle correction for hyperopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41:3726–3731.5. Lim HT, Cho SI, Lee SJ, Park SH. Long-term observations on the emmetropization of the high hyperopia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002; 43:1230–1237.6. Saunders KJ, Woodhouse JM, Westall CA. Emmetropisation in human infancy: rate of change is related to initial refractive error. Vision Res. 1995; 35:1325–1328.7. Na SJ, Choi NY, Park MR, Park SC. Long-term follow-up results of hyperopic refractive change. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2005; 46:1704–1710.8. Lambert SR, Lynn MJ. Longitudinal changes in the spherical equivalent refractive error of children with accommodative esotropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90:357–361.9. Lambert SR, Lynn M. Longitudinal changes in the cylinder power of children with accommodative esotropia. J AAPOS. 2007; 11:55–59.10. Hung LF, Crawford ML, Smith EL. Spectacle lenses alter eye growth and the refractive status of young monkeys. Nat Med. 1995; 1:761–765.11. Irving EL, Sivak JG, Callender MG. Refractive plasticity of the developing chick eye. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1992; 12:448–456.12. Ingram RM, Gill LE, Lambert TW. Effect of spectacles on changes of spherical hypermetropia in infants who did, and did not, have strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84:324–326.13. Park KA, Kim SA, Oh SY. Effect of age wearing prescription glasses on changes of refractive error in accommodative esotropia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2009; 50:247–252.14. Kim IN, Paik HJ. Long-term changes of hyperopic refractive error in refractive accommodative esotropia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2015; 56:580–585.15. Baldwin WR. Refractive status of infants and children. In : Rosenbloom AA, Morgan MW, editors. Principles and Practice of Paediatric Optometry. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott;1990. p. 104–152.16. Ehrlich DL, Braddick OJ, Atkinson J, et al. Infant emmetropization: longitudinal changes in refraction components from nine to twenty months of age. Optom Vis Sci. 1997; 74:822–843.17. Grosvenor TP, Flom MC. Refractive anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.18. Ingram RM, Arnold PE, Dally S, Lucas J. Emmetropisation, squint, and reduced visual acuity after treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991; 75:414–416.19. Cotter SA, Frantz KA. Strabismus: detection, diagnosis and classification. In : Moore BD, editor. Eye Care for Infants and Young Children. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann;1997. p. 123–154.20. Babinsky E, Candy TR. Why do only some hyperopes become strabismic? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54:4941–4955.21. Jones-Jordan L, Wang X, Scherer RW, Mutti DO. Spectacle correction versus no spectacles for prevention of strabismus in hyperopic children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (8):CD007738.22. Lin Z, Vasudevan B, Jhanji V, et al. Near work, outdoor activity, and their association with refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 2014; 91:376–382.23. Lin Z, Vasudevan B, Mao GY, et al. The influence of near work on myopic refractive change in urban students in Beijing: a three-year follow-up report. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016; 254:2247–2255.24. Dirani M, Chan YH, Gazzard G, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in Singaporean Chinese children: the strabismus, amblyopia, and refractive error in young Singaporean Children (STARS) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51:1348–1355.25. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study (MEPEDS) Group. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in African-American and Hispanic preschool children: the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:1990–2000.e1.26. Lam CS, Edwards M, Millodot M, Goh WS. A 2-year longitudinal study of myopia progression and optical component changes among Hong Kong schoolchildren. Optom Vis Sci. 1999; 76:370–380.27. Fan DS, Rao SK, Cheung EY, et al. Astigmatism in Chinese preschool children: prevalence, change, and effect on refractive development. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004; 88:938–941.28. Shih YF, Ho TC, Chen MS, et al. Experimental myopia in chickens induced by corneal astigmatism. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994; 72:597–601.29. Hirsch MJ. Changes in astigmatism during the first eight years of school--an interim report from the Ojai longitudinal study. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1963; 40:127–132.30. O'Donoghue L, Rudnicka AR, McClelland JF, et al. Refractive and corneal astigmatism in white school children in northern ireland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52:4048–4053.31. Harvey EM, Miller JM, Twelker JD, Sherrill DL. Longitudinal change and stability of refractive, keratometric, and internal astigmatism in childhood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 56:190–198.32. O'Donoghue L, Breslin KM, Saunders KJ. The changing profile of astigmatism in childhood: the NICER Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56:2917–2925.33. American Academy of Ophthalmology Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Panel. Preferred practice pattern guidelines: Pediatric eye evaluations. San Franciso: American Academy of Ophthalmology;2012.34. Donahue SP. How often are spectacles prescribed to "normal" preschool children? J AAPOS. 2004; 8:224–229.35. Robaei D, Rose K, Kifley A, Mitchell P. Patterns of spectacle use in young Australian school children: findings from a population-based study. J AAPOS. 2005; 9:579–583.36. Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Mitchell P. Refractive error and patterns of spectacle use in 12-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113:1567–1573.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Long-Term Follow-Up of Refractive Accommodative Esotropia: Decompensation and Cessation of Spectacle Use

- Long-Term Results of Three Cases of Radial Keratotomy

- Long-Term Changes of Hyperopic Refractive Error in Refractive Accommodative Esotropia

- A Study of the Ocular Findings According to Subdivided Myepia

- Relationship between Uncorrected Visual Acuity and Refractive Error in Visual Acuity Test of Children