Yonsei Med J.

2016 Sep;57(5):1087-1094. 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1087.

Early Effects of Intensive Lipid-Lowering Treatment on Plaque Characteristics Assessed by Virtual Histology Intravascular Ultrasound

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea. mkhong61@yuhs.ac

- 2Cardiovascular Division, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Yeungnam University Medical Center, Daegu, Korea.

- 3Cardiovascular Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Severance Biomedical Science Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2374152

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1087

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The effects of short-term intensive lipid-lowering treatment on coronary plaque composition have not yet been sufficiently evaluated. We investigated the influence of short-term intensive lipid-lowering treatment on quantitative and qualitative changes in plaque components of non-culprit lesions in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, randomized, open-label, single-center trial. Seventy patients who underwent both baseline and three-month follow-up virtual histology intravascular ultrasound were randomly assigned to either an intensive lipid-lowering treatment group (ezetimibe/simvastatin 10/40 mg, n=34) or a control statin treatment group (pravastatin 20 mg, n=36). Using virtual histology intravascular ultrasound, plaque was characterized as fibrous, fibro-fatty, dense calcium, or necrotic core. Changes in plaque components during the three-month lipid-lowering treatment were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS

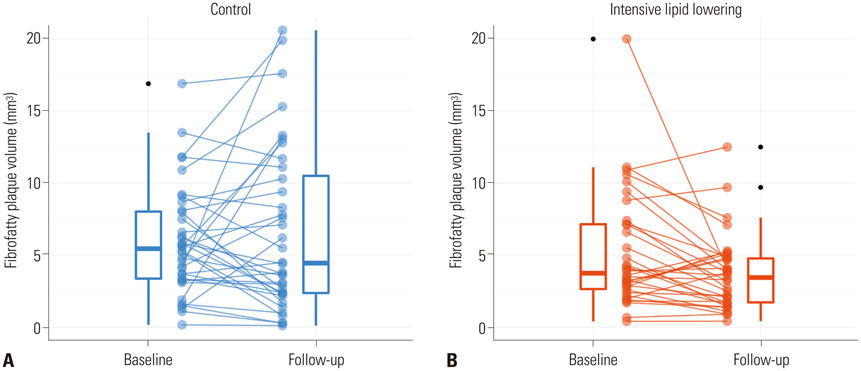

Compared with the control statin treatment group, there was a significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the intensive lipid-lowering treatment group (-20.4±17.1 mg/dL vs. -36.8±17.4 mg/dL, respectively; p<0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in baseline, three-month follow-up, or serial changes of gray-scale intravascular ultrasound parameters between the two groups. The absolute volume of fibro-fatty plaque was significantly reduced in the intensive lipid-lowering treatment group compared with the control group (-1.5±3.4 mm3 vs. 0.8±4.7 mm3, respectively; p=0.024). A linear correlation was found between changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and changes in the absolute volumes of fibro-fatty plaque (p<0.001, R2=0.209).

CONCLUSION

Modification of coronary plaque may be attainable after only three months of intensive lipid-lowering treatment.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Aged

Cholesterol, LDL/*blood/drug effects

Coronary Artery Disease/*diagnostic imaging

Drug Administration Schedule

Ezetimibe, Simvastatin Drug Combination/*administration & dosage

Female

Humans

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors/*administration & dosage

Male

Middle Aged

Plaque, Atherosclerotic/*diagnostic imaging

Pravastatin/administration & dosage

Prospective Studies

Time Factors

Treatment Outcome

Ultrasonography, Interventional

Cholesterol, LDL

Ezetimibe, Simvastatin Drug Combination

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors

Pravastatin

Figure

Reference

-

1. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet. 1994; 344:1383–1389.2. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:1349–1357.3. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002; 360:7–22.4. Pitt B, Waters D, Brown WV, van Boven AJ, Schwartz L, Title LM, et al. Aggressive lipid-lowering therapy compared with angioplasty in stable coronary artery disease. Atorvastatin versus Revascularization Treatment Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:70–76.

Article5. Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, Rouleau JL, Rutherford JD, Cole TG, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:1001–1009.

Article6. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, Ganz P, Oliver MF, Waters D, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001; 285:1711–1718.

Article7. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:1495–1504.

Article8. LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, Shear C, Barter P, Fruchart JC, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1425–1435.

Article9. Effect of simvastatin on coronary atheroma: the Multicentre Anti-Atheroma Study (MAAS). Lancet. 1994; 344:633–638.10. Jukema JW, Bruschke AV, van Boven AJ, Reiber JH, Bal ET, Zwinderman AH, et al. Effects of lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels. The Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS). Circulation. 1995; 91:2528–2540.

Article11. Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 291:1071–1080.

Article12. Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, et al. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006; 295:1556–1565.

Article13. Okazaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyauchi K, Shimada K, Kurata T, Sato H, et al. Early statin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: demonstration of the beneficial effect on atherosclerotic lesions by serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis during half a year after coronary event: the ESTABLISH Study. Circulation. 2004; 110:1061–1068.

Article14. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:8 Suppl. C13–C18.

Article15. Libby P, Schoenbeck U, Mach F, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Current concepts in cardiovascular pathology: the role of LDL cholesterol in plaque rupture and stabilization. Am J Med. 1998; 104:14S–18S.

Article16. Nasu K, Tsuchikane E, Katoh O, Tanaka N, Kimura M, Ehara M, et al. Effect of fluvastatin on progression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque evaluated by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:689–696.

Article17. Lee SW, Hau WK, Kong SL, Chan KK, Chan PH, Lam SC, et al. Virtual histology findings and effects of varying doses of atorvastatin on coronary plaque volume and composition in statin-naive patients: the VENUS study. Circ J. 2012; 76:2662–2672.

Article18. Puri R, Libby P, Nissen SE, Wolski K, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, et al. Long-term effects of maximally intensive statin therapy on changes in coronary atheroma composition: insights from SATURN. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014; 15:380–388.

Article19. Toi T, Taguchi I, Yoneda S, Kageyama M, Kikuchi A, Tokura M, et al. Early effect of lipid-lowering therapy with pitavastatin on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Comparison with atorvastatin. Circ J. 2009; 73:1466–1472.

Article20. Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD, Bailey SR, Erbel R, Fitzgerald PJ, et al. American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 37:1478–1492.

Article21. Nair A, Kuban BD, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Nissen SE, Vince DG. Coronary plaque classification with intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. Circulation. 2002; 106:2200–2206.

Article22. Rodriguez-Granillo GA, García-García HM, Mc Fadden EP, Valgimigli M, Aoki J, de Feyter P, et al. In vivo intravascular ultrasoundderived thin-cap fibroatheroma detection using ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:2038–2042.

Article23. Hong MK, Park DW, Lee CW, Lee SW, Kim YH, Kang DH, et al. Effects of statin treatments on coronary plaques assessed by volumetric virtual histology intravascular ultrasound analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:679–688.

Article24. Moreno PR, Fuster V. The year in atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:2099–2110.

Article25. Suh Y, Kim BK, Shin DH, Kim JS, Ko YG, Choi D, et al. Impact of statin treatment on strut coverage after drug-eluting stent implantation. Yonsei Med J. 2015; 56:45–52.

Article26. Sudhop T, Lütjohann D, Kodal A, Igel M, Tribble DL, Shah S, et al. Inhibition of intestinal cholesterol absorption by ezetimibe in humans. Circulation. 2002; 106:1943–1948.

Article27. Davis HR Jr, Zhu LJ, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Maguire M, Liu J, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2004; 279:33586–33592.

Article28. Ballantyne CM, Blazing MA, King TR, Brady WE, Palmisano J. Efficacy and safety of ezetimibe co-administered with simvastatin compared with atorvastatin in adults with hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2004; 93:1487–1494.

Article29. Ballantyne CM, Abate N, Yuan Z, King TR, Palmisano J. Dose-comparison study of the combination of ezetimibe and simvastatin (Vytorin) versus atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the Vytorin Versus Atorvastatin (VYVA) study. Am Heart J. 2005; 149:464–473.

Article30. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387–2397.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Early Differential Changes in Coronary Plaque Composition According to Plaque Stability Following Statin Initiation in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Classification and Analysis by Intravascular Ultrasound-Virtual Histology

- An Overview of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy-Intravascular Ultrasound and Its Applications in Coronary Artery Disease

- Relationship between Coronary Artery Calcium Score by Multidetector Computed Tomography and Plaque Components by Virtual Histology Intravascular Ultrasound

- Roles of Intravascular Ultrasound in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Analysis of Plaque Composition in Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion Lesion Using Virtual Histology-Intravascular Ultrasound