J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Dec;31(12):2042-2050. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.2042.

Acquired Bilateral Dyspigmentation on Face and Neck: Clinically Appropriate Approaches

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Dermatology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. bell711@hanmail.net

- 2Department of Medical Device Management & Research, SAIHST, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2355637

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.2042

Abstract

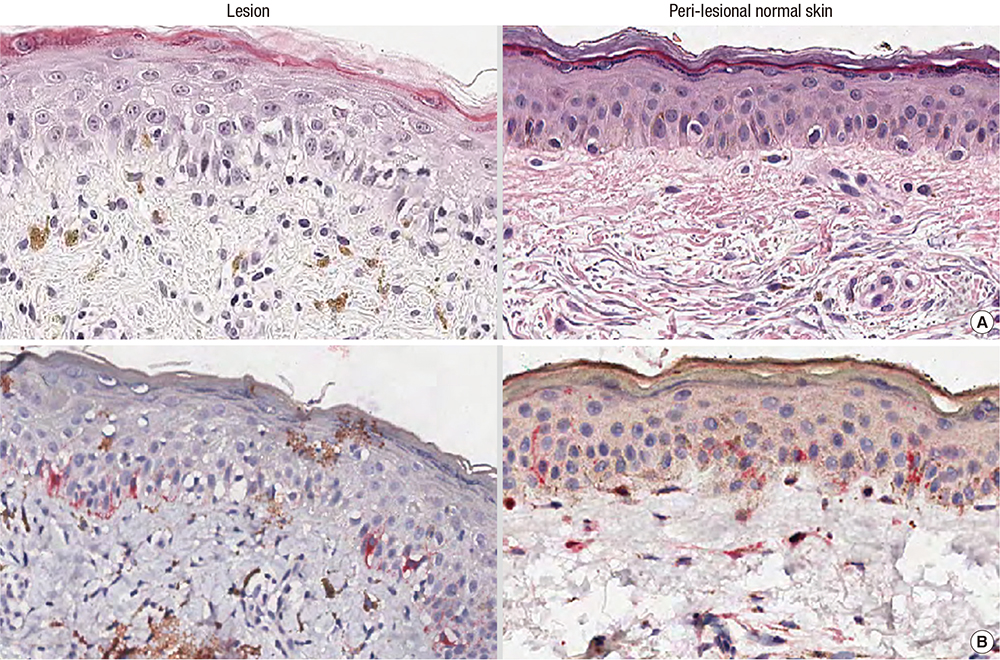

- Facial dyspigmentation in Asian women often poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Recently, a distinctive bilateral hyperpigmentation of face and neck has occasionally been observed. This study was performed to investigate the clinico-pathological features of this dyspigmentation as well as proper treatment approaches. We retrospectively investigated the medical records including photographs, routine laboratory tests, histopathologic studies of both lesional and peri-lesional normal skin and patch test of thirty-one patients presented acquired bizarre hyperpigmentation on face and neck. The mean age of patients was 52.3 years and the mean duration of dyspigmentation was 24.2 months. In histologic evaluations of lesional skin, a significantly increased liquefactive degeneration of basal layer, pigmentary incontinence and lymphocytic infiltration were noted, whereas epidermal melanin or solar elastosis showed no statistical differences. Among 19 patients managed with a step-by-step approach, seven improved with using only topical anti-inflammatory agents and moisturizer, and 12 patients gained clinical benefit after laser therapy without clinical aggravation. Both clinical and histopathologic findings of the cases suggest a distinctive acquired hyperpigmentary disorder related with subclinical inflammation. Proper step-by-step evaluation and management of underlying subclinical inflammation would provide clinical benefit.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Pérez-Bernal A, Muñoz-Pérez MA, Camacho F. Management of facial hyperpigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000; 1:261–268.2. Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Hyperpigmentation and melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007; 6:195–202.3. Patel AB, Kubba R, Kubba A. Clinicopathological correlation of acquired hyperpigmentary disorders. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013; 79:367–375.4. Khanna N, Rasool S. Facial melanoses: Indian perspective. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011; 77:552–563.5. de Souza A, el-Azhary RA, Camilleri MJ, Wada DA, Appert DL, Gibson LE. In search of prognostic indicators for lymphomatoid papulosis: a retrospective study of 123 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 66:928–937.6. Molinar VE, Taylor SC, Pandya AG. What’s new in objective assessment and treatment of facial hyperpigmentation? Dermatol Clin. 2014; 32:123–135.7. Grimes PE. Management of hyperpigmentation in darker racial ethnic groups. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009; 28:77–85.8. Gernone A, Frassanito MA, Pellegrino A, Vacca A, Dammacco F. Multiple myeloma and mycosis fungoides in the same patient: clinical, immunologic, and molecular studies. Ann Hematol. 2002; 81:326–331.9. Kang HY. Melasma and aspects of pigmentary disorders in Asians. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012; 139:Suppl 4. S144–7.10. Lachapelle JM, Maibach HI. The International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Patch Testing and Prick Testing. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer;2009.11. Serrano G, Pujol C, Cuadra J, Gallo S, Aliaga A. Riehl’s melanosis: pigmented contact dermatitis caused by fragrances. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989; 21:1057–1060.12. Grimes PE, Yamada N, Bhawan J. Light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural alterations in patients with melasma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27:96–101.13. Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, Hojyo T, Dominguez-Soto L. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992; 31:90–94.14. Park JY, Kim YC, Lee ES, Park KC, Kang HY. Acquired bilateral melanosis of the neck in perimenopausal women. Br J Dermatol. 2012; 166:662–665.15. Jung JM, Han JS, Won CH, Chang SE, Lee MW, Choi JH, Moon KC. Pigmented contact dermatitis caused by hydroquinone: an unusual presentation and allergen. Korean J Dermatol. 2015; 53:173–175.16. Ebihara T, Nakayama H. Pigmented contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1997; 15:593–599.17. Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier/Saunders;2012.18. Rorsman H. Riehl’s melanosis. Int J Dermatol. 1982; 21:75–78.19. Shenoi SD, Rao R. Pigmented contact dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007; 73:285–287.20. Li YH, Liu J, Chen JZ, Wu Y, Xu TH, Zhu X, Liu W, Wei HC, Gao XH, Chen HD. A pilot study of intense pulsed light in the treatment of Riehl’s melanosis. Dermatol Surg. 2011; 37:119–122.21. Chuah SY, Leow YH, Goon AT, Theng CT, Chong WS. Photopatch testing in Asians: a 5-year experience in Singapore. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2013; 29:116–120.22. Czarnobilska E, Obtułowicz K, Dyga W, Gołuch A, Zwiewka M. Eosinophilia, ECP and Ecp/Eo ratio in allergic and non-allergic diseases. Przegl Lek. 2005; 62:765–768.23. Lever WF, Elder DE. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2009.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Tree Cases of Aquired bilateral Nevus of Ota-like Marcules

- Facial feminization procedures: the western approaches to the forehead

- Endoscopic Laser-Assisted Repair in a Case of Acquired Bilateral Choanal Stenosis

- A Case of Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota-like Macules Accompanying the Common Blue Nevus

- Acquired, Bilateral Nevus of Ota-like Macules (ABNOM) Associated with Ota's Nevus: Case Report