J Korean Med Sci.

2016 Dec;31(12):1863-1873. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.1863.

Epidemiological Characteristics and Risk Factors of Dengue Infection in Korean Travelers

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. hesss@snu.ac.kr

- 2Global Center for Infectious Diseases, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Institute of Endemic Diseases, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2355612

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.12.1863

Abstract

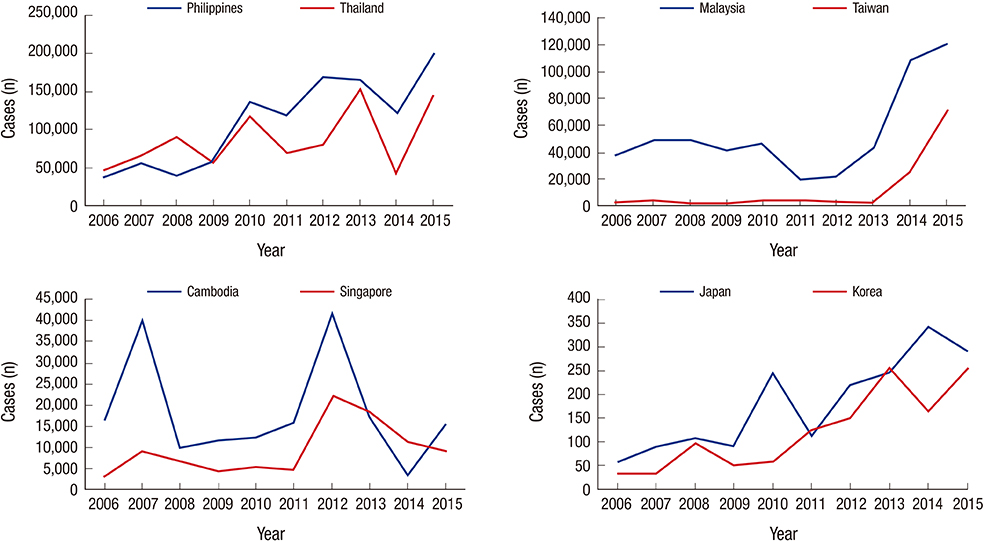

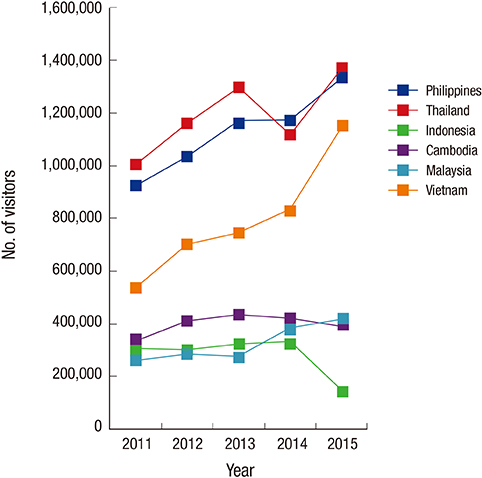

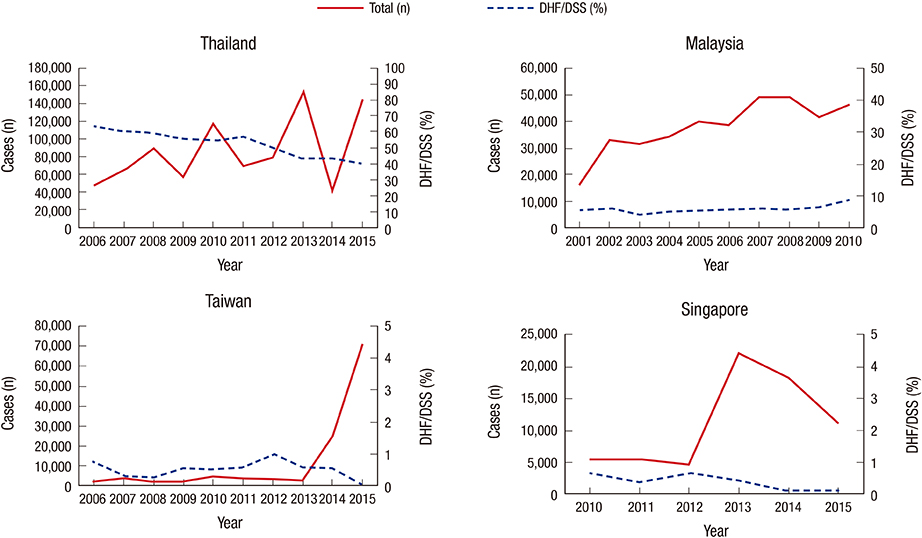

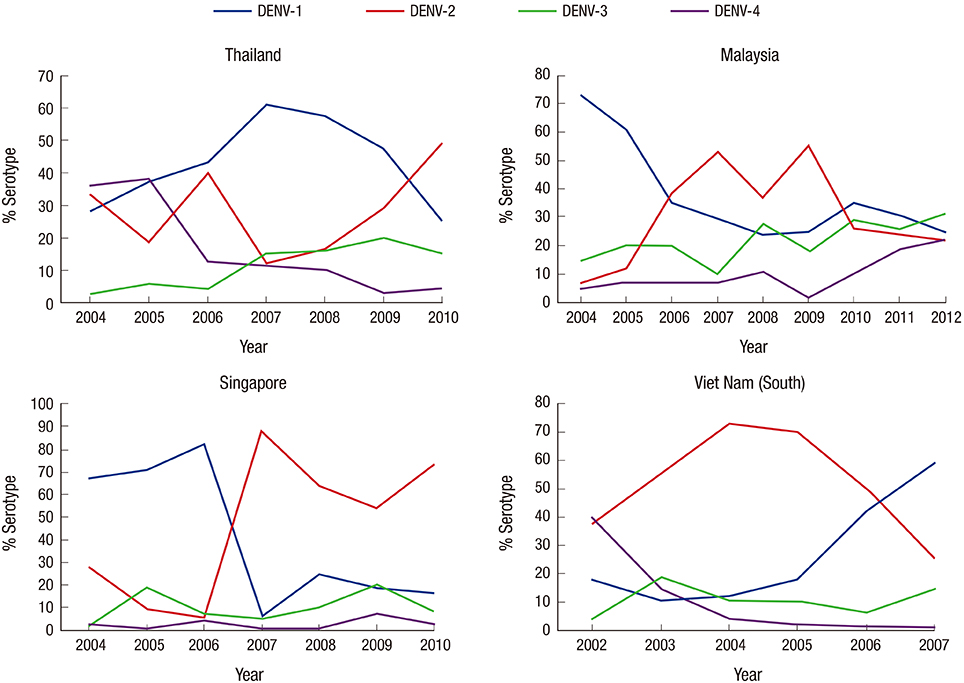

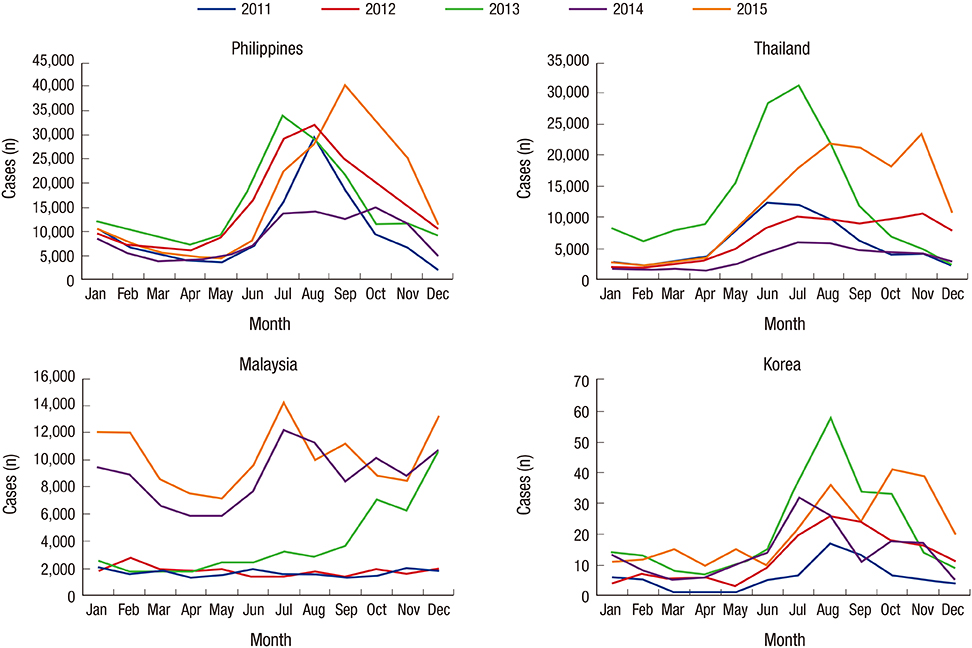

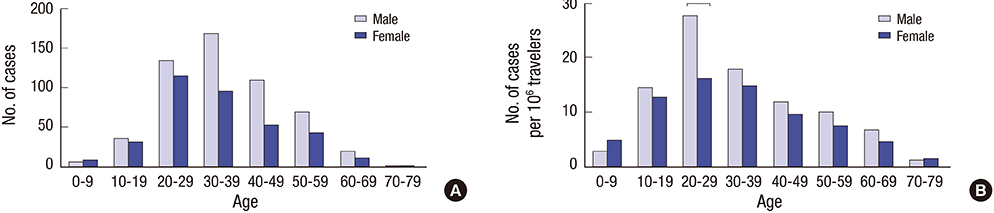

- Dengue viral infection has rapidly spread around the world in recent decades. In Korea, autochthonous cases of dengue fever have not been confirmed yet. However, imported dengue cases have been increased since 2001. The risk of developing severe dengue in Korean has been increased by the accumulation of past-infected persons with residual antibodies to dengue virus and the remarkable growth of traveling to endemic countries in Southeast Asia. Notably, most of imported dengue cases were identified from July to December, suggesting that traveling during rainy season of Southeast Asia is considered a risk factor for dengue infection. Analyzing national surveillance data from 2011 to 2015, males aged 20-29 years are considered as the highest risk group. But considering the age and gender distribution of travelers, age groups 10-49 except 20-29 years old males have similar risks for infection. To minimize a risk of dengue fever and severe dengue, travelers should consider regional and seasonal dengue situation. It is recommended to prevent from mosquito bites or to abstain from repetitive visit to endemic countries. In addition, more active surveillance system and monitoring the prevalence asymptomatic infection and virus serotypes are required to prevent severe dengue and indigenous dengue outbreak.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/.2. Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013; 496:504–507.3. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infectious disease annual report of 2015 [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://cdc.go.kr/CDC/info/CdcKrInfo0302.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1132-MNU1138-MNU0038.4. Gratz NG. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Med Vet Entomol. 2004; 18:215–227.5. Huy NT, Van Giang T, Thuy DH, Kikuchi M, Hien TT, Zamora J, Hirayama K. Factors associated with dengue shock syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7:e2412.6. Guzman MG, Alvarez M, Halstead SB. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: an historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Arch Virol. 2013; 158:1445–1459.7. Costa VV, Fagundes CT, Souza DG, Teixeira MM. Inflammatory and innate immune responses in dengue infection: protection versus disease induction. Am J Pathol. 2013; 182:1950–1961.8. Ubol S, Phuklia W, Kalayanarooj S, Modhiran N. Mechanisms of immune evasion induced by a complex of dengue virus and preexisting enhancing antibodies. J Infect Dis. 2010; 201:923–935.9. Khurram M, Qayyum W, Hassan SJ, Mumtaz S, Bushra HT, Umar M. Dengue hemorrhagic fever: comparison of patients with primary and secondary infections. J Infect Public Health. 2014; 7:489–495.10. Guzman MG, Vazquez S. The complexity of antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. Viruses. 2010; 2:2649–2662.11. Semenza JC, Sudre B, Miniota J, Rossi M, Hu W, Kossowsky D, Suk JE, Van Bortel W, Khan K. International dispersal of dengue through air travel: importation risk for Europe. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014; 8:e3278.12. Nakamura N, Arima Y, Shimada T, Matsui T, Tada Y, Okabe N. Incidence of dengue virus infection among Japanese travellers, 2006 to 2010. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2012; 3:39–45.13. Huang X, Yakob L, Devine G, Frentiu FD, Fu SY, Hu W. Dynamic spatiotemporal trends of imported dengue fever in Australia. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:30360.14. World Health Organization Western Pacific Region. Dengue situation updates [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/DengueSituationUpdates/en/.15. Ministry of Public Health, Department of Disease Control, Bureau of Epidemiology (TH). National disease surveillance (report 506) [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.boe.moph.go.th/boedb/surdata/index.php.16. Official Portal for Ministry of Health Malaysia. Annual report MOH [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.moh.gov.my/english.php.17. Mohd-Zaki AH, Brett J, Ismail E, L’Azou M. Epidemiology of dengue disease in Malaysia (2000-2012): a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014; 8:e3159.18. Ministry of Health (SG). Infectious diseases statistics [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/statistics/infectiousDiseasesStatistics.html.19. Centers for Disease Control (TW). Taiwan national infectious disease statistics system [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/en/Default.aspx.20. National Institute of Infectious Diseases (JP). NESID annual surveillance data (notifiable diseases)2014-2 [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/en/survei/2085-idwr/ydata/6058-report-ea2014-20.html.21. Limkittikul K, Brett J, L’Azou M. Epidemiological trends of dengue disease in Thailand (2000–2011): a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014; 8:e3241.22. Ministry of Health (SG). Communicable diseases surveillance in Singapore 2014 [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/Publications/Reports/2015/communicable-diseases-surveillance-in-singapore-2014.html.23. Coudeville L, Garnett GP. Transmission dynamics of the four dengue serotypes in southern Vietnam and the potential impact of vaccination. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e51244.24. Korea Tourism Organization. Korean departure statistics [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://kto.visitkorea.or.kr/kor/notice/data/statis/profit/board/list.kto?instanceId=294.25. Tourism Knowledge & Information System. Korean departure statistics [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.tour.go.kr/.26. Chastel C. Global threats from emerging viral diseases. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2007; 191:1563–1577.27. Gould EA, Higgs S. Impact of climate change and other factors on emerging arbovirus diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009; 103:109–121.28. Edillo FE, Halasa YA, Largo FM, Erasmo JN, Amoin NB, Alera MT, Yoon IK, Alcantara AC, Shepard DS. Economic cost and burden of dengue in the Philippines. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015; 92:360–366.29. Ministry of Health of Republic of Indonesia. Info dengue [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.depkes.go.id/index.php?lg=LN02.30. Haryanto S, Hayati RF, Yohan B, Sijabat L, Sihite IF, Fahri S, Meutiawati F, Halim JA, Halim SN, Soebandrio A, et al. The molecular and clinical features of dengue during outbreak in Jambi, Indonesia in 2015. Pathog Glob Health. 2016; 110:119–129.31. Karyanti MR, Uiterwaal CS, Kusriastuti R, Hadinegoro SR, Rovers MM, Heesterbeek H, Hoes AW, Bruijning-Verhagen P. The changing incidence of dengue haemorrhagic fever in Indonesia: a 45-year registry-based analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014; 14:412.32. Bennett SN, Drummond AJ, Kapan DD, Suchard MA, Muñoz-Jordán JL, Pybus OG, Holmes EC, Gubler DJ. Epidemic dynamics revealed in dengue evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2010; 27:811–818.33. Adams B, Holmes EC, Zhang C, Mammen MP Jr, Nimmannitya S, Kalayanarooj S, Boots M. Cross-protective immunity can account for the alternating epidemic pattern of dengue virus serotypes circulating in Bangkok. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006; 103:14234–14239.34. Amarasinghe A, Kuritsk JN, Letson GW, Margolis HS. Dengue virus infection in Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011; 17:1349–1354.35. Were F. The dengue situation in Africa. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2012; 32:Suppl 1. 18–21.36. Baba M, Villinger J, Masiga DK. Repetitive dengue outbreaks in East Africa: a proposed phased mitigation approach may reduce its impact. Rev Med Virol. 2016; 26:183–196.37. Jaenisch T, Junghanss T, Wills B, Brady OJ, Eckerle I, Farlow A, Hay SI, McCall PJ, Messina JP, Ofula V, et al. Dengue expansion in Africa-not recognized or not happening? Emerg Infect Dis. 2014; 20:e140487.38. de la C Sierra B. Kourí G, Guzmán MG. Race: a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Arch Virol. 2007; 152:533–542.39. Chacón-Duque JC, Adhikari K, Avendaño E, Campo O, Ramirez R, Rojas W, Ruiz-Linares A, Restrepo BN, Bedoya G. African genetic ancestry is associated with a protective effect on dengue severity in Colombian populations. Infect Genet Evol. 2014; 27:89–95.40. Amexo M, Tolhurst R, Barnish G, Bates I. Malaria misdiagnosis: effects on the poor and vulnerable. Lancet. 2004; 364:1896–1898.41. Normile D. Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts. Science. 2013; 342:415.42. Dejnirattisai W, Jumnainsong A, Onsirisakul N, Fitton P, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Puttikhunt C, Edwards C, Duangchinda T, Supasa S, et al. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science. 2010; 328:745–748.43. Suh SJ, Seo YS, Ahn JH, Park EB, Lee SJ, Sohn JU, Um SH. A case of imported dengue fever with acute hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2007; 13:556–559.44. Kang YJ, Choi SY, Kang IJ, Lee JE, Seo MH, Lee TH, Ghim BK. Dengue fever mimicking acute appendicitis: a case report. Infect Chemother. 2009; 41:236–239.45. Ler TS, Ang LW, Yap GS, Ng LC, Tai JC, James L, Goh KT. Epidemiological characteristics of the 2005 and 2007 dengue epidemics in Singapore - similarities and distinctions. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2011; 2:24–29.46. International Association for Medical Assistance to Travelers. General health risks: dengue [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at https://www.iamat.org/country/indonesia/risk/dengue.47. Mudin RN. Dengue incidence and the prevention and control program in Malaysia. Int Med J Malays. 2015; 14:5–10.48. Bravo L, Roque VG, Brett J, Dizon R, L’Azou M. Epidemiology of dengue disease in the Philippines (2000–2011): a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014; 8:e3027.49. Prasith N, Keosavanh O, Phengxay M, Stone S, Lewis HC, Tsuyuoka R, Matsui T, Phongmanay P, Khamphaphongphane B, Arima Y. Assessment of gender distribution in dengue surveillance data, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2013; 4:17–24.50. Wichmann O, Hongsiriwon S, Bowonwatanuwong C, Chotivanich K, Sukthana Y, Pukrittayakamee S. Risk factors and clinical features associated with severe dengue infection in adults and children during the 2001 epidemic in Chonburi, Thailand. Trop Med Int Health. 2004; 9:1022–1029.51. Fukusumi M, Arashiro T, Arima Y, Matsui T, Shimada T, Kinoshita H, Arashiro A, Takasaki T, Sunagawa T, Oishi K. Dengue sentinel traveler surveillance: monthly and yearly notification trends among Japanese travelers, 2006–2014. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016; 10:e0004924.52. Anker M, Arima Y. Male-female differences in the number of reported incident dengue fever cases in six Asian countries. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2011; 2:17–23.53. Gibbons RV, Kalanarooj S, Jarman RG, Nisalak A, Vaughn DW, Endy TP, Mammen MP Jr, Srikiatkhachorn A. Analysis of repeat hospital admissions for dengue to estimate the frequency of third or fourth dengue infections resulting in admissions and dengue hemorrhagic fever, and serotype sequences. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007; 77:910–913.54. Wu PC, Lay JG, Guo HR, Lin CY, Lung SC, Su HJ. Higher temperature and urbanization affect the spatial patterns of dengue fever transmission in subtropical Taiwan. Sci Total Environ. 2009; 407:2224–2233.55. Gubler DJ. Dengue, urbanization and globalization: the unholy trinity of the 21st century. Trop Med Health. 2011; 39:3–11.56. Neiderud CJ. How urbanization affects the epidemiology of emerging infectious diseases. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2015; 5:27060.57. World Health Organization. Dengue control: global strategy for dengue prevention and control, 2012–2020 [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.who.int/denguecontrol/9789241504034/en/.58. Duong V, Lambrechts L, Paul RE, Ly S, Lay RS, Long KC, Huy R, Tarantola A, Scott TW, Sakuntabhai A, et al. Asymptomatic humans transmit dengue virus to mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015; 112:14688–14693.59. Chastel C. Eventual role of asymptomatic cases of dengue for the introduction and spread of dengue viruses in non-endemic regions. Front Physiol. 2012; 3:70.60. de Wazières B, Gil H, Vuitton DA, Dupond JL. Nosocomial transmission of dengue from a needlestick injury. Lancet. 1998; 351:498.61. Chen LH, Wilson ME. Transmission of dengue virus without a mosquito vector: nosocomial mucocutaneous transmission and other routes of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:e56–60.62. Nemes Z, Kiss G, Madarassi EP, Peterfi Z, Ferenczi E, Bakonyi T, Ternak G. Nosocomial transmission of dengue. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:1880–1881.63. World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. Dengue [Internet]. accessed on 31 August 2016. Available at http://www.searo.who.int/entity/vector_borne_tropical_diseases/data/data_factsheet/en/.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Prospects for dengue vaccines for travelers

- Comparison of the Epidemiological Aspects of Imported Dengue Cases between Korea and Japan, 2006–2010

- Risk Assessment of the Occurrence of Blood Products Infected with Dengue Virus Based on Travelers to the Areas of Dengue Outbreak

- Estimation of the Size of Dengue and Zika Infection Among Korean Travelers to Southeast Asia and Latin America, 2016–2017

- Dengue Fever