Korean Circ J.

2016 Mar;46(2):169-178. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.2.169.

Psychiatric Characteristics of the Cardiac Outpatients with Chest Pain

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Jeju National University, Jeju, Korea. valgom@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2344468

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.2.169

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

A cardiologist's evaluation of psychiatric symptoms in patients with chest pain is rare. This study aimed to determine the psychiatric characteristics of patients with and without coronary artery disease (CAD) and explore their relationship with the intensity of chest pain.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

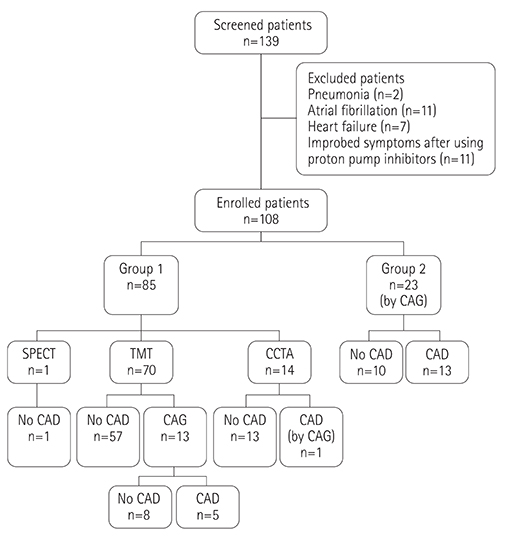

Out of 139 consecutive patients referred to the cardiology outpatient department, 31 with atypical chest pain (heartburn, acid regurgitation, dyspnea, and palpitation) were excluded and 108 were enrolled for the present study. The enrolled patients underwent complete numerical rating scale of chest pain and the symptom checklist for minor psychiatric disorders at the time of first outpatient visit. The non-CAD group consisted of patients with a normal stress test, coronary computed tomography angiogram, or coronary angiogram, and the CAD group included those with an abnormal coronary angiogram.

RESULTS

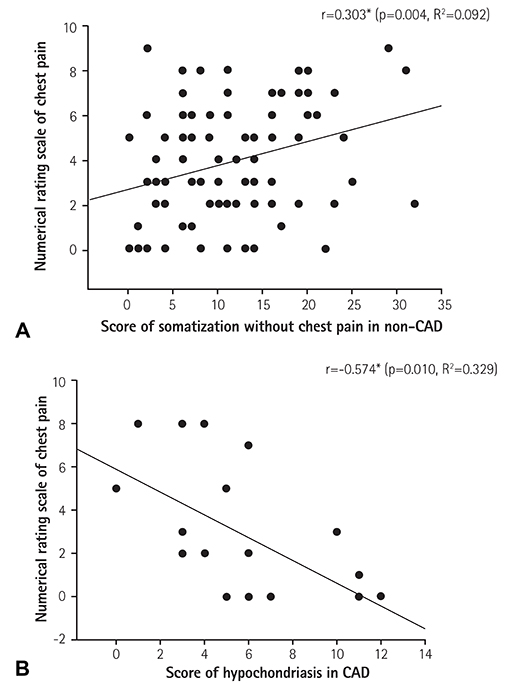

Nineteen patients (17.6%) were diagnosed with CAD. No differences in the psychiatric characteristics were observed between the groups. "Feeling tense", "self-reproach", and "trouble falling asleep" were more frequently observed in the non-CAD (p=0.007; p=0.046; p=0.044) group. In a multiple linear regression analysis with a stepwise selection, somatization without chest pain in the non-CAD group and hypochondriasis in the CAD group were linearly associated with the intensity of chest pain (β=0.108, R2=0.092, p=0.004; β= -0.525, R2=0.290, p=0.010).

CONCLUSION

No differences in psychiatric characteristics were observed between the groups. The intensity of chest pain was linearly associated with somatization without chest pain in the non-CAD group and inversely linearly associated with hypochondriasis in the CAD group.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Papanicolaou MN, Califf RM, Hlatky MA, et al. Prognostic implications of angiographically normal and insignificantly narrowed coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1986; 58:1181–1187.2. Hoffmann U, Nagurney JT, Moselewski F, et al. Coronary multidetector computed tomography in the assessment of patients with acute chest pain. Circulation. 2006; 114:2251–2260.3. Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989; 86:262–266.4. Mayou R, Bryant B, Forfar C, Clark D. Non-cardiac chest pain and benign palpitations in the cardiac clinic. Br Heart J. 1994; 72:548–553.5. Channer KS, Papouchado M, James MA, Rees JR. Anxiety and depression in patients with chest pain referred for exercise testing. Lancet. 1985; 2:820–823.6. Cormier LE, Katon W, Russo J, Hollifield M, Hall ML, Vitaliano PP. Chest pain with negative cardiac diagnostic studies. Relationship to psychiatric illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988; 176:351–358.7. Dammen T, Arnesen H, Ekeberg O, Friis S. Psychological factors, pain attribution and medical morbidity in chest-pain patients with and without coronary artery disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004; 26:463–469.8. Zachariae R, Melchiorsen H, Frøbert O, Bjerring P, Bagger JP. Experimental pain and psychologic status of patients with chest pain with normal coronary arteries or ischemic heart disease. Am Heart J. 2001; 142:63–71.9. Tennant C, Mihailidou A, Scott A, et al. Psychological symptom profiles in patients with chest pain. J Psychosom Res. 1994; 38:365–371.10. Kisely SR. The relationship between admission to hospital with chest pain and psychiatric disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998; 32:172–179.11. Mayou RA, Bryant BM, Sanders D, Bass C, Klimes I, Forfar C. A controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for non-cardiac chest pain. Psychol Med. 1997; 27:1021–1031.12. Cannon RO 3rd, Quyyumi AA, Mincemoyer R, et al. Imipramine in patients with chest pain despite normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med. 1994; 330:1411–1417.13. Mayou RA, Bass CM, Bryant BM. Management of non-cardiac chest pain: from research to clinical practice. Heart. 1999; 81:387–392.14. Varia I, Logue E, O'Connor C, et al. Randomized trial of sertraline in patients with unexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin. Am Heart J. 2000; 140:367–372.15. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:e215–e367.16. Jeong W, Chang H. Rliability and Validity of Korean Version of Symptom Check list for Minor psychiatric Disorders (SCL-MPD). J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1987; 26:15.17. Rohani A, Akbari V, Zarei F. Anxiety and depression symptoms in chest pain patients referred for the exercise stress test. Heart Views. 2011; 12:161–164.18. Bass C, Wade C. Chest pain with normal coronary arteries: a comparative study of psychiatric and social morbidity. Psychol Med. 1984; 14:51–61.19. Ladwig KH, Hoberg E, Busch R. Psychological comorbidity in patients with alarming chest pain symptoms. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1998; 48:46–54.20. Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999; 99:2192–2217.21. Watkins LL, Grossman P, Krishnan R, Sherwood A. Anxiety and vagal control of heart rate. Psychosom Med. 1998; 60:498–502.22. Lown B, Verrier R, Corbalan R. Psychologic stress and threshold for repetitive ventricular response. Science. 1973; 182:834–836.23. Ramasubbu R. Insulin resistance: a metabolic link between depressive disorder and atherosclerotic vascular diseases. Med Hypotheses. 2002; 59:537–551.24. Gold PW, Loriaux DL, Roy A, et al. Responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone in the hypercortisolism of depression and Cushing's disease. Pathophysiologic and diagnostic implications. N Engl J Med. 1986; 314:1329–1335.25. Reynolds K, Pietrzak RH, El-Gabalawy R, Mackenzie CS, Sareen J. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in U.S. older adults: findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry. 2015; 14:74–81.26. D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008; 117:743–753.27. Chen AC, Dworkin SF, Haug J, Gehrig J. Human pain responsivity in a tonic pain model: psychological determinants. Pain. 1989; 37:143–160.28. Kim JY, Kim N, Seo PJ, et al. Association of sleep dysfunction and emotional status with gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013; 19:344–354.29. Dempe C, Jünger J, Hoppe S, et al. Association of anxious and depressive symptoms with medication nonadherence in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Psychosom Res. 2013; 74:122–127.30. Meyer T, Hussein S, Lange HW, Herrmann-Lingen C. Anxiety is associated with a reduction in both mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events five years after coronary stenting. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015; 22:75–82.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Psychogenic symptoms in patients with noncardiac chest pain

- Erratum: Psychiatric Characteristics of the Cardiac Outpatients with Chest Pain

- Chest Pain in Children and Adolescents

- Etiology and treatment of chest pain in children and adolescents

- Non-cardiac Chest Pain in Japan: Prevalence, Impact, and Consultation Behavior - A Population-based Study