J Korean Med Sci.

2015 Sep;30(9):1347-1353. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.9.1347.

Differences in Hands-off Time According to the Position of a Second Rescuer When Switching Compression in Pre-hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Provided by Two Bystanders: A Randomized, Controlled, Parallel Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea. 3syellow@naver.com

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Inje University, Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 3Department of Physical Education, Kyungnam University, Changwon, Korea.

- 4Department of Emergency Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University, Anyang, Korea.

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Gachon University Gil Hospital, Incheon, Korea.

- KMID: 2344163

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.9.1347

Abstract

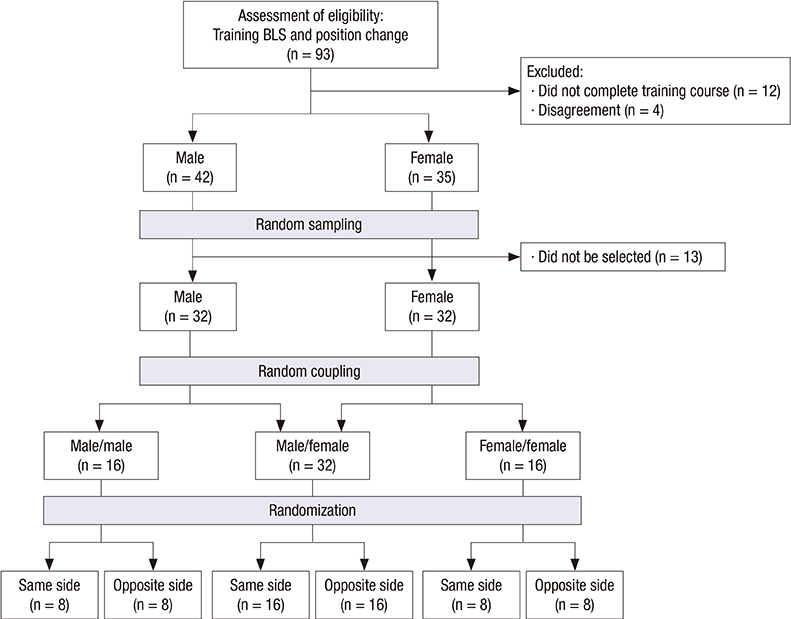

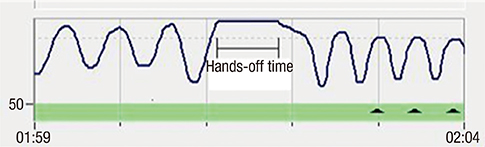

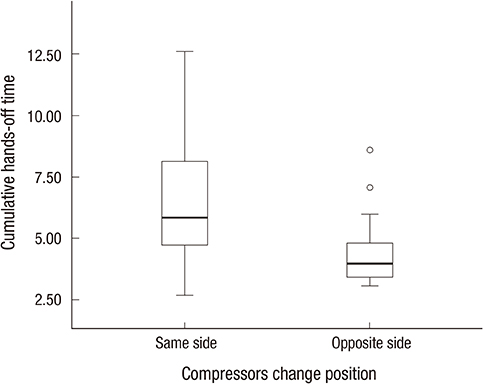

- The change of compressing personnel will inevitably accompany hands off time when cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is performed by two or more rescuers. The present study assessed whether changing compression by a second rescuer located on the opposite side (OS) of the first rescuer can reduce hands-off time compared to CPR on the same side (SS) when CPR is performed by two rescuers. The scenario of this randomized, controlled, parallel simulation study was compression-only CPR by two laypersons in a pre-hospital situation. Considering sex ratio, 64 participants were matched up in 32 teams equally divided into two gender groups, i.e. , homogenous or heterogeneous. Each team was finally allocated to one of two study groups according to the position of changing compression (SS or OS). Every team performed chest compression for 8 min and 10 sec, with chest compression changed every 2 min. The primary endpoint was cumulative hands-off time. Cumulative hands-off time of the SS group was about 2 sec longer than the OS group, and was significant (6.6 +/- 2.6 sec vs. 4.5 +/- 1.5 sec, P = 0.005). The range of hands off time of the SS group was wider than for the OS group. The mean hands-off times of each rescuer turn significantly shortened with increasing number of turns (P = 0.005). A subgroup analysis in which cumulative hands-off time was divided into three subgroups in 5-sec intervals revealed that about 70% of the SS group was included in subgroups with delayed hands-off time > or = 5 sec, with only 25% of the OS group included in these subgroups (P = 0.033). Changing compression at the OS of each rescuer reduced hands-off time compared to the SS in prehospital hands-only CPR provided by two bystanders.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation/methods/*statistics & numerical data

Clinical Competence/*statistics & numerical data

Emergency Medical Services/*statistics & numerical data

Female

Heart Arrest/epidemiology/*prevention & control

Heart Massage/methods/*statistics & numerical data

Humans

Male

Republic of Korea/epidemiology

Treatment Outcome

Workload/*statistics & numerical data

Young Adult

Figure

Reference

-

1. Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, Sunde K, Koster RW, Smith GB, Perkins GD. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010; 81:1305–1352.2. Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010; 122:S729–S767.3. Bobrow BJ, Clark LL, Ewy GA, Chikani V, Sanders AB, Berg RA, Richman PB, Kern KB. Minimally interrupted cardiac resuscitation by emergency medical services for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2008; 299:1158–1165.4. Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Cave DM, Hazinski MF, Lerner EB, Rea TD, Sayre MR, Swor RA. Part 5: adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010; 122:S685–S705.5. Abella BS, Sandbo N, Vassilatos P, Alvarado JP, O'Hearn N, Wigder HN, Hoffman P, Tynus K, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB. Chest compression rates during cardiopulmonary resuscitation are suboptimal: a prospective study during in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2005; 111:428–434.6. Fries M, Tang W. How does interruption of cardiopulmonary resuscitation affect survival from cardiac arrest? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005; 11:200–203.7. Valenzuela TD, Kern KB, Clark LL, Berg RA, Berg MD, Berg DD, Hilwig RW, Otto CW, Newburn D, Ewy GA. Interruptions of chest compressions during emergency medical systems resuscitation. Circulation. 2005; 112:1259–1265.8. Wik L. Rediscovering the importance of chest compressions to improve the outcome from cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2003; 58:267–269.9. Kern KB. Limiting interruptions of chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003; 58:273–274.10. Ilper H, Kunz T, Pfleger H, Schalk R, Byhahn C, Ackermann H, Breitkreutz R. Comparative quality analysis of hands-off time in simulated basic and advanced life support following European Resuscitation Council 2000 and 2005 guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2012; 29:95–99.11. Walcott GP, Melnick SB, Walker RG, Banville I, Chapman FW, Killingsworth CR, Ideker RE. Effect of timing and duration of a single chest compression pause on short-term survival following prolonged ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2009; 80:458–462.12. Yu T, Weil MH, Tang W, Sun S, Klouche K, Povoas H, Bisera J. Adverse outcomes of interrupted precordial compression during automated defibrillation. Circulation. 2002; 106:368–372.13. Yost D, Phillips RH, Gonzales L, Lick CJ, Satterlee P, Levy M, Barger J, Dodson P, Poggi S, Wojcik K, et al. Assessment of CPR interruptions from transthoracic impedance during use of the LUCAS mechanical chest compression system. Resuscitation. 2012; 83:961–965.14. Edelson DP, Abella BS, Kramer-Johansen J, Wik L, Myklebust H, Barry AM, Merchant RM, Hoek TL, Steen PA, Becker LB. Effects of compression depth and pre-shock pauses predict defibrillation failure during cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2006; 71:137–145.15. Manders S, Geijsel FE. Alternating providers during continuous chest compressions for cardiac arrest: every minute or every two minutes? Resuscitation. 2009; 80:1015–1018.16. Sato Y, Weil MH, Sun S, Tang W, Xie J, Noc M, Bisera J. Adverse effects of interrupting precordial compression during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:733–736.17. Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Berg RA, Ewy GA. Efficacy of chest compression-only BLS CPR in the presence of an occluded airway. Resuscitation. 1998; 39:179–188.18. Berg RA, Sanders AB, Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Heidenreich JW, Porter ME, Ewy GA. Adverse hemodynamic effects of interrupting chest compressions for rescue breathing during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2001; 104:2465–2470.19. Yang CW, Wang HC, Chiang WC, Hsu CW, Chang WT, Yen ZS, Ko PC, Ma MH, Chen SC, Chang SC. Interactive video instruction improves the quality of dispatcher-assisted chest compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation in simulated cardiac arrests. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37:490–495.20. Hong DY, Park SO, Lee KR, Baek KJ, Shin DH. A different rescuer changing strategy between 30:2 cardiopulmonary resuscitation and hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation that considers rescuer factors: a randomised cross-over simulation study with a time-dependent analysis. Resuscitation. 2012; 83:353–359.21. Jiang C, Zhao Y, Chen Z, Chen S, Yang X. Improving cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the emergency department by real-time video recording and regular feedback learning. Resuscitation. 2010; 81:1664–1669.22. Lucía A, de las Heras JF, Pérez M, Elvira JC, Carvajal A, Álvarez AJ, Chicharro JL. The importance of physical fitness in the performance of adequate cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Chest. 1999; 115:158–164.23. Hansen D, Vranckx P, Broekmans T, Eijnde BO, Beckers W, Vandekerckhove P, Broos P, Dendale P. Physical fitness affects the quality of single operator cardiocerebral resuscitation in healthcare professionals. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012; 19:28–34.24. Russo SG, Neumann P, Reinhardt S, Timmermann A, Niklas A, Quintel M, Eich CB. Impact of physical fitness and biometric data on the quality of external chest compression: a randomised, crossover trial. BMC Emerg Med. 2011; 11:20.25. Miles DS, Underwood PD Jr, Nolan DJ, Frey MA, Gotshall RW. Metabolic, hemodynamic, and respiratory responses to performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1984; 9:141–147.26. Jones CM, Thorne CJ, Colter PS, Macrae A, Brown GA, Hulme J. Rescuers may vary their side of approach to a casualty without impact on cardiopulmonary resuscitation performance. Emerg Med J. 2013; 30:74–75.27. Heidenreich JW, Berg RA, Higdon TA, Ewy GA, Kern KB, Sanders AB. Rescuer fatigue: standard versus continuous chest-compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med. 2006; 13:1020–1026.28. Ashton A, McCluskey A, Gwinnutt CL, Keenan AM. Effect of rescuer fatigue on performance of continuous external chest compressions over 3 min. Resuscitation. 2002; 55:151–155.29. Ochoa FJ, Ramalle-Gómara E, Lisa V, Saralegui I. The effect of rescuer fatigue on the quality of chest compressions. Resuscitation. 1998; 37:149–152.30. Min MK, Yeom SR, Ryu JH, Kim YI, Park MR, Han SK, Lee SH, Cho SJ. A 10-s rest improves chest compression quality during hands-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a prospective, randomized crossover study using a manikin model. Resuscitation. 2013; 84:1279–1284.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Does Switching Rescuers Every 2 Minutes Improve the Quality of Chest Compression Provided in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation?

- A case of left ventricle rupture complicating lay rescuer cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Comparison of the Alternating Rescuer Method between Every Minute and Two Minutes During Continuous Chest Compression in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation According to the 2010 Guidelines

- COMPARISON OF THE QUALITY OF TWO-RESCUER CPR VS THREE-RESCUER CPR

- Can a Rescuer Gazing Point Intervention Improve the Depth of Chest Compressions in Hands-only Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation? A Randomized Simulation Study