J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2015 Mar;56(3):388-395. 10.3341/jkos.2015.56.3.388.

Outpatient Distribution for Glaucoma Evaluation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Nune Eye Hospital, Seoul, Korea. youngjhong@gmail.com

- KMID: 2339045

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2015.56.3.388

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To analyze the reasons for glaucoma evaluation and distribution of new patients visiting the glaucoma department.

METHODS

In a retrospective study, 330 new patients underwent ocular examination using Goldmann applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, optic disc analysis, optical coherence tomography, and Humphrey perimeter under suspicion of glaucoma for the first time in the Glaucoma Department from January 2013 to December 2013. We analyzed the reasons and their diagnostic outcomes.

RESULTS

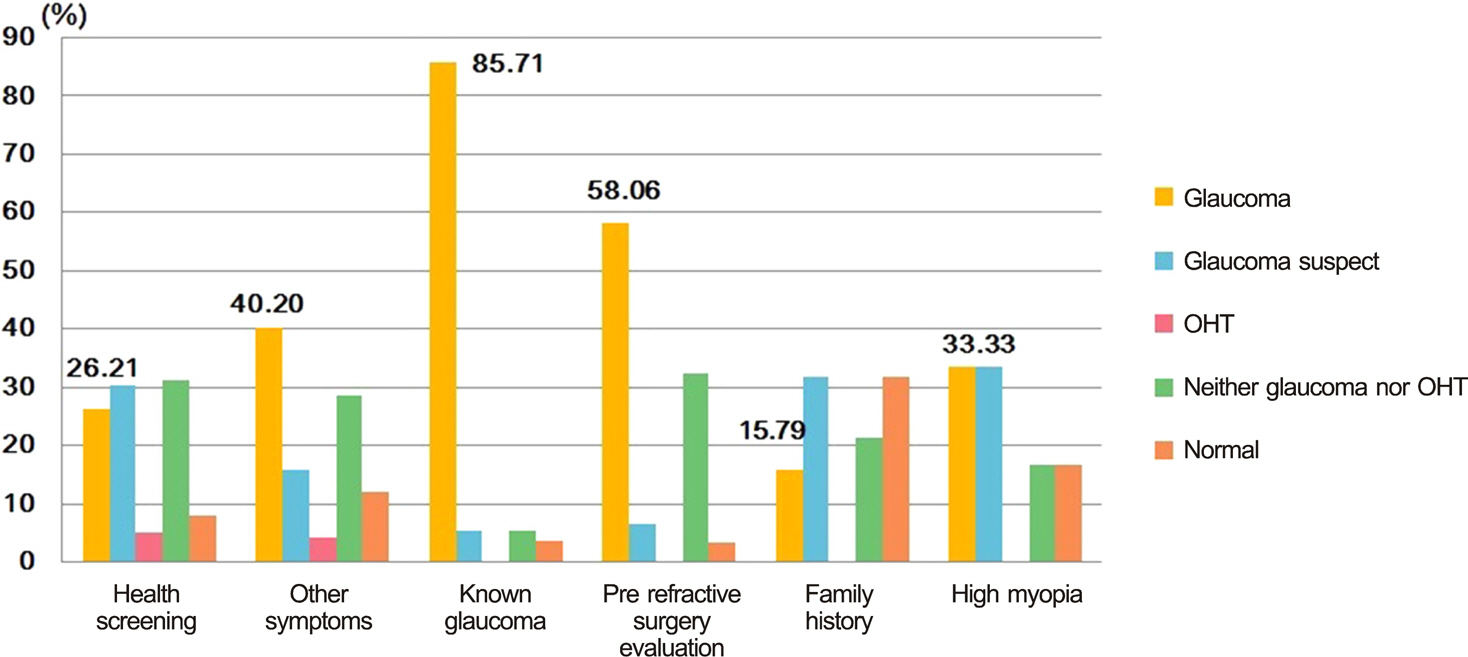

The reasons for glaucoma evaluation were health screening (103 patients, 32.49%), other symptoms (102 patients, 31.55%), known glaucoma (56 patients, 17.67%), pre-refractive surgery evaluation (31 patients, 9.78%), family history (19 patients, 5.99%), and high myopia (6 patients, 1.89%). The diagnostic outcomes were as follows: glaucoma (139 patients, 43.85%), glaucoma suspect (60 patients, 18.93%), ocular hypertension (9 patients, 2.84%), neither glaucoma nor ocular hypertension (79 patients, 24.92%), normal (30 patients, 9.46%). The percentages of confirmed glaucoma according to the reasons for glaucoma evaluation were as follows: health screening, 26.21%; other symptoms, 40.20%; known glaucoma, 85.71%; pre-refractive surgery evaluation, 58.06%; family history, 15.79% and high myopia, 33.33%.

CONCLUSIONS

The reasons for glaucoma evaluation were diverse. Glaucoma was confirmed in 43.85% of the patients and the predicted value of positive test for glaucoma including glaucoma suspect and ocular hypertension was 65.62%.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Path to Glaucoma Diagnosis

Kwan Bok Lee, Min Kyung Kim, Mi Jin Kim, Sang Il Ahn, Young Hoon Hwang

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2016;57(5):794-799. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2016.57.5.794.

Reference

-

References

1. Bowling B, Chen SD, Salmon JF. Outcomes of referrals by com-munity optometrists to a hospital glaucoma service. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89:1102–4.

Article2. Kwak HW, Joo MJ, Yoo JH. The significance of fundus photography without mydriasis during health mass screening. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1997; 38:1585–9.3. Chung YS, Kim JM, Sohn YH. Diagnostic outcomes of patients suspicious for glaucoma referred from the company health screening. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2006; 47:1444–8.4. Kim JH, Kang SY, Kim NR, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of glaucoma among Korean adults. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011; 25:110–5.

Article5. Yoon KC, Mun GH, Kim SD, et al. Prevalence of eye diseases in South Korea: data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2009. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011; 25:421–33.

Article6. Kim CS, Seong GJ, Lee NH, Song KC; Namil Study Group, Korean Glaucoma Society. Prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in central South Korea the Namil study. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1024–30.7. Kim YY, Lee JH, Ahn MD, Kim CY; Namil Study Group, Korean Glaucoma Society. Angle closure in the Namil study in central South Korea. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130:1177–83.

Article8. Iwase A, Suzuki Y, Araie M, et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: the Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:1641–8.9. Sawaguchi S, Sakai H, Iwase A, et al. Prevalence of primary angle closure and primary angle-closure glaucoma in a southwestern rural population of Japan: the Kumejima Study. Ophthalmology. 2012; 119:1134–42.10. Oh SW, Ahn CS, Rhym MH. A clinical analysis on 186 cases of glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1970; 11:17–20.11. Joo JH, Hong C. Clinical study on Korean glaucomatous patients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1987; 28:583–8.12. Shin SG, Ahn JH, Rho SH. A clinical analysis on 456 cases of glaucoma among outpatients during 5 years. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1987; 28:1021–6.13. Song MS, Kim DG, Kim HJ. Clinical study on glaucomatous patients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1989; 30:755–9.14. Song GW, Jin KH, Kim JM. Clinical data on glaucomatous patients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1990; 31:1179–83.15. Hwang IC, Jeong SK, Yang KJ. A clinical study on glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1992; 33:394–400.16. Lee CK, Cho YJ, Hong YJ. Distribution of glaucoma outpatients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1995; 36:1020–7.17. Lee CH, Jin GH, Kim DM. Clinical analysis on glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1998; 39:362–8.18. Kim JY, Hong SP, Kwon JY. Comparison of clinical features in three types of primary glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2004; 45:607–13.19. Mitchell P, Hourihan F, Sandbach J, Wang JJ. The relationship between glaucoma and myopia: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:2010–5.