J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2010 Jan;51(1):141-144.

Intraocular Foreign Body of a Vitreous Cutter Tip Fragment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea. eyelovehyun@hanmail.net

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report a case of intraocular foreign body of a vitreous cutter tip fragment.

CASE SUMMARY

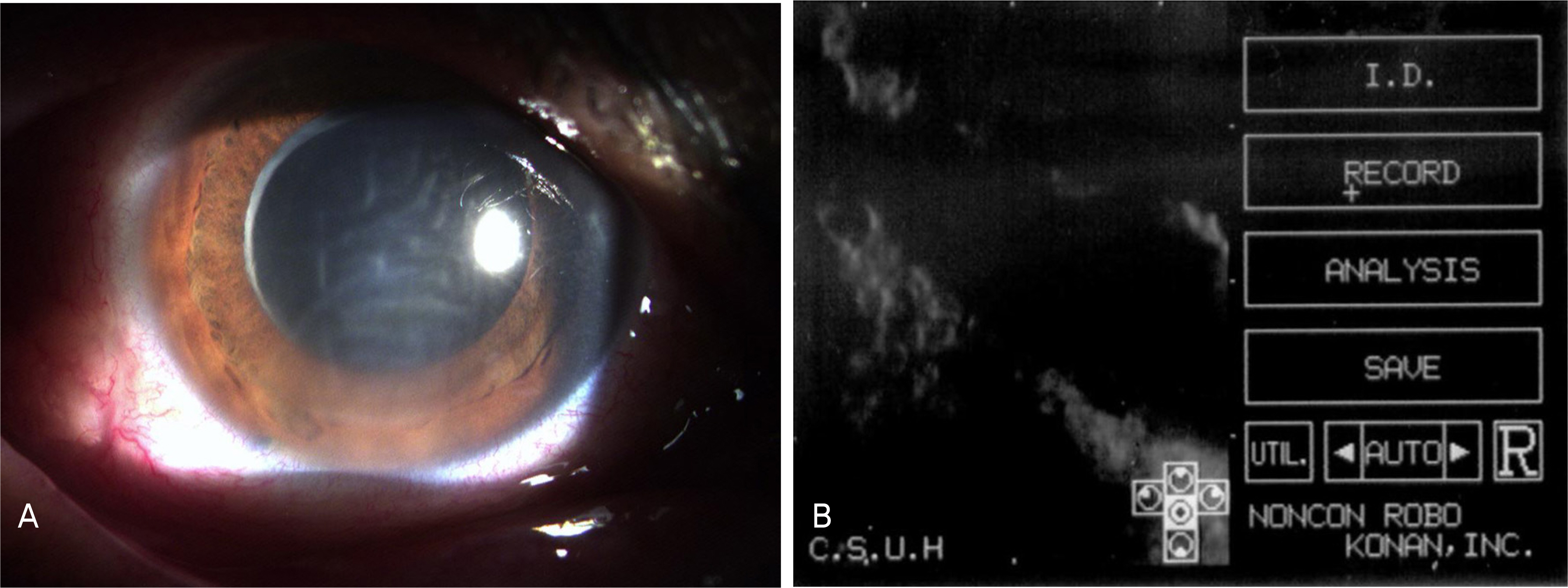

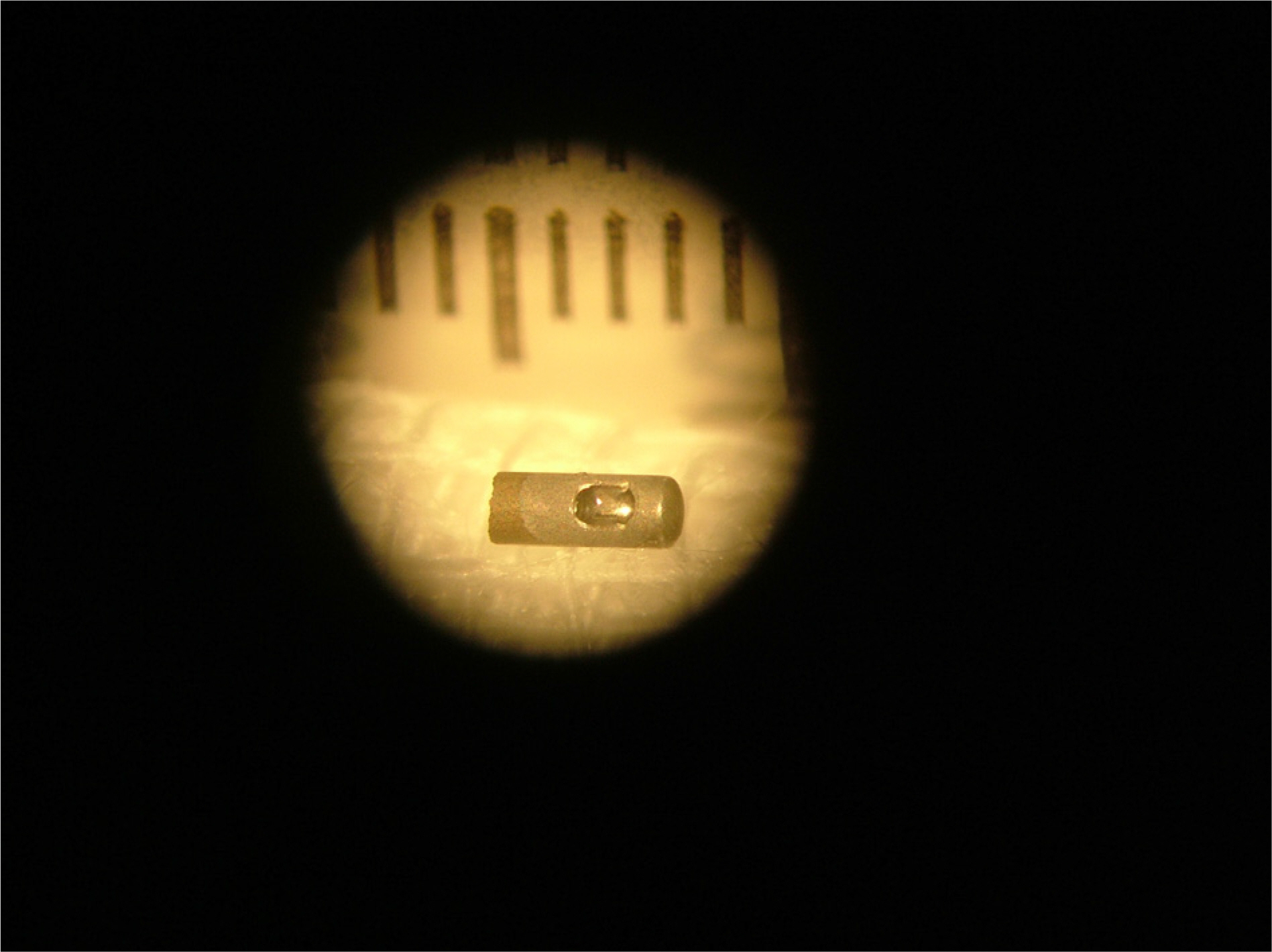

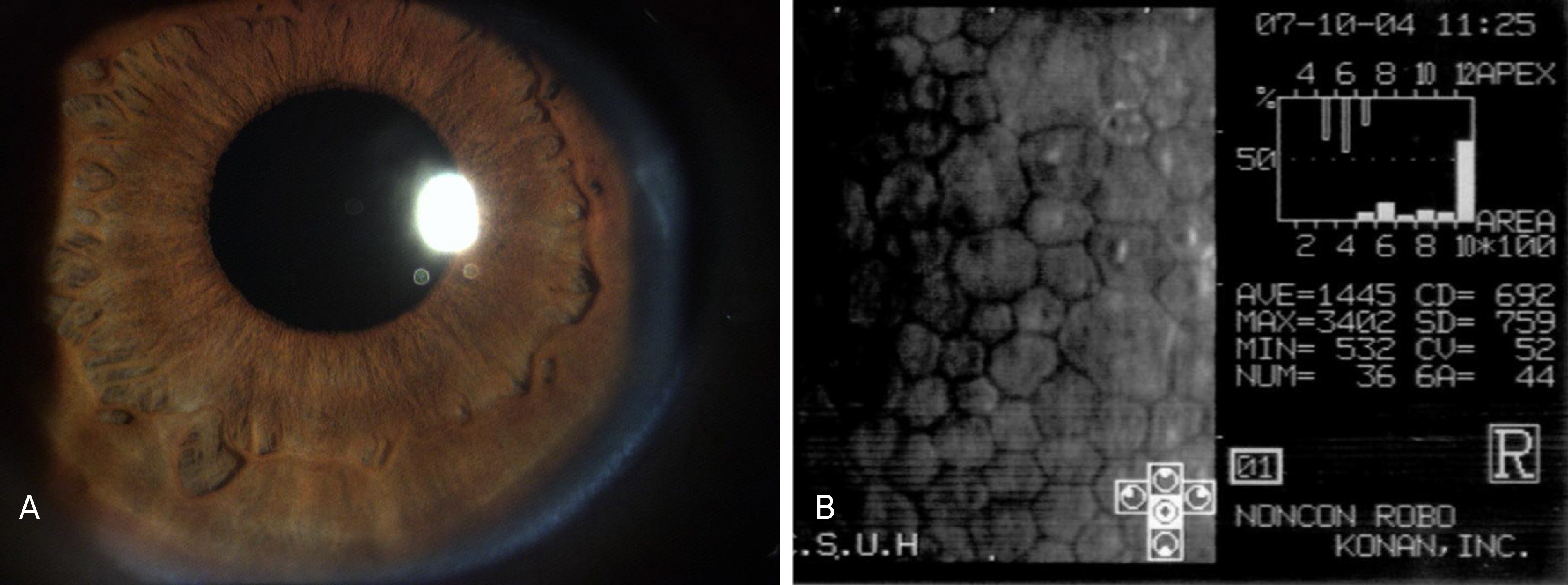

A 60-year-old women was referred by her ophthalmologist with a two-day history of visual disturbance in her right eye. She had undergone pars plana vitrectomy, barrier laser and C3F8 gas injection due to pseudophakic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in our retinal service center four months previously. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of her right eye showed cornea stromal edema with Descemet membrane folding. Gonioscopic examination revealed a metallic foreign body in the direction of the 6-o'clock anterior chamber angle. Anterior chamber irrigation with successful removal of the metallic foreign body using intraocular foreign body forceps was performed. The removed intraocular foreign body was a vitrectomy cutter tip fragment 20 gauge in size and 3 mm in length. After surgery, the corneal stromal edema disappeared and her visual acuity in the right eye recovered.

CONCLUSIONS

Intraoperative breakage of vitreous cutter tips can occur and cause toxic ocular tissue reaction. Care should be taken against vitreous cutter tip breakage during vitrectomy.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Greven CM, Engelbrecht NE, Slusher MM, Nagy SS. Intraocular foreign bodies; management, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:608–12.2. Coleman DJ, Lucas BC, Rondeau MJ, Chang S. Management of intraocular foreign bodies. Ophthalmology. 1987; 94:1647–53.

Article3. Williams DF, Miller WF, Abrams GW, Lewis H. Results and prognostic factors in penetrating ocular injuries with retained intraocular foreign bodies. Ophthalmology. 1988; 95:911–6.

Article4. Takeda N, Numata K, Hirata H, et al. Current Aspects in Ophthalmology: Proceedings of the XII congress of the Asia Pacific Acadamy of Ophthalmology, May 1991. Amsterdam: Elsevier;1992. p. 1869–70.5. Khane SC, Mukai S. Posterior segment intraocular foreign bodies. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1995; 35:151–61.6. Dannenberg AL, Parver LM, Flower CJ. Penetrating eye injuries related to assault: the national eye travma system refistry. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992; 110:849–52.7. Nanda SK, Mieler WF, Murphy ML. Penetrating ocular injuries secondary to motor vehicle accidents. Ophthalmology. 1993; 100:201–7.

Article8. Mines M, Thach A, Mallonee S, et al. Ocular injuries sustained by survivors of the Oklahoma city bombing. Ophthalmology. 2000; 107:837–43.9. John G, Witherspoon CD, Feist RM, et al. Ocular lawnmower injuries. Ophthalmology. 1988; 95:1367–70.

Article10. Lambert HM, Sipperley JO. Intraocular foreign body from a nylon line grass trimmer. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983; 15:936–7.11. Fraser SG, Dowd TC, Bosanquet RC. Intraocular caterpillar hairs (setae): clinical course and management. Eye. 1994; 8:596–8.

Article12. Inoue M, Noda K, Ishida S, et al. Intraoperative Breakage of a 25-gauge Vitreous Cutter. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004; 138:867–9.

Article13. Ballantyne JF. Siderosis bulbi. Br J Ophthalmol. 1954; 38:727–33.

Article14. Grant WM. Toxicology of the Eye; Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, Plants, Toxins, and Venoms. 3rd ed.Springfield IL: Charles C Thomas;1986. p. 526–32.15. Davidson M. Siderosis bulbi. Am J Ophthalmol. 1933; 16:331–5.

Article16. Talamo JH, Topping TM, Maumenee AE, Green WR. Ultrastructural studies of cornea, iris, and lens in case of siderosis bulbi. Ophthalmology. 1985; 92:1675–80.17. Duke-Elder S, editor. System of Ophthalmology. ⅩⅣ:Injuries. Pt. 1: Mechanical Injuries. St.Louis: CV Mosby;1972. p. 525–44.

Article18. Riley MV, Giblin FJ. Toxic effects of hydrogen peroxide on cornea endothelium. Curr Eye Res. 1982–1983; 2:451–8.19. Delamere NA, Paterson CA, Cotton TR. Lens cation transport and permeability changes following exposure to hydrogen peroxide. Exp Eye Res. 1983; 37:45–53.

Article20. Hull DS, Csukas S, Green K, Livingston V. Hydrogen peroxide and corneal endothelium. Acta Ophthalmol. 1981; 59:409–21.

Article21. Wise JB. Treatment of experimental siderosis bulbi, vitreous hemorrhage, and corneal bloodstaining with deferoxamine. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966; 75:698–707.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Re: Intraocular Foreign Body of a Vitreous Cutter Tip Fragment

- Magnet Extraction of Intraocular Foreign Body in the Vitreous

- The Diagnostic Value of Time-amplitude ultrasonography in Ocular Disease

- Localization and Extraction Technique of Magnetic Intraocular Foreign Body: I. Convenient and Accurate Technique of Localization

- A Case of Posterior Scleritis Following Traumatic Intraocular Foreign Body Removal