J Korean Acad Nurs Adm.

2015 Jan;21(1):64-76. 10.11111/jkana.2015.21.1.64.

Systematic Search for Guidelines to Prevent Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections-Part II: Using the Ovid MEDLINE

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Nursing, Honam University, Korea.

- 2College of Nursing, Chonnam National University, Korea. choijy@jnu.ac.kr

- 3Chonnam Research Institute of Nursing Science, Korea.

- 4Department of Nursing, Mokpo National University, Korea.

- KMID: 2321280

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2015.21.1.64

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To implement evidence-based nursing, it is important to know where and how to find the best available evidence. This study was conducted to identify the results of a search from Ovid MEDLINE and to compare the results from Ovid MEDLINE with those from PubMed MEDLINE.

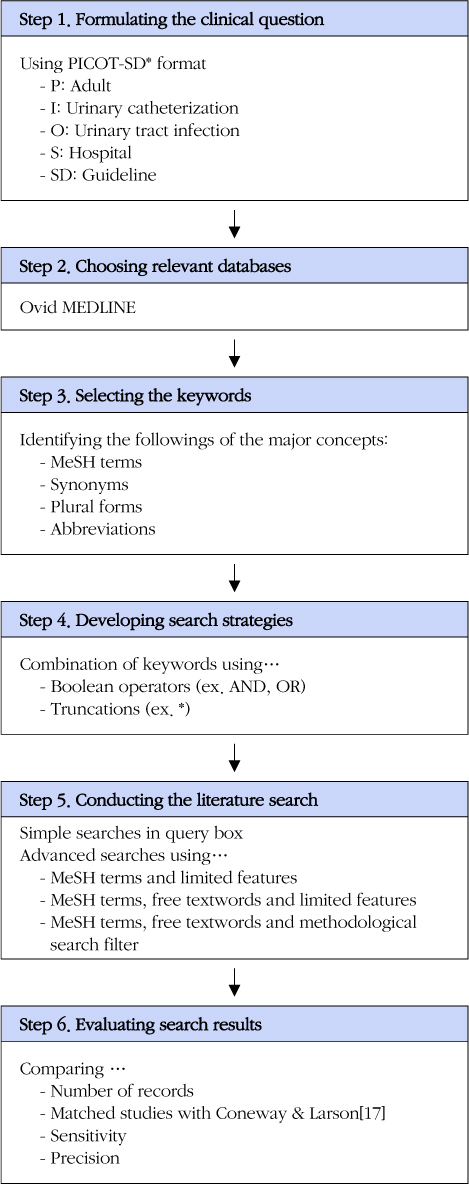

METHODS

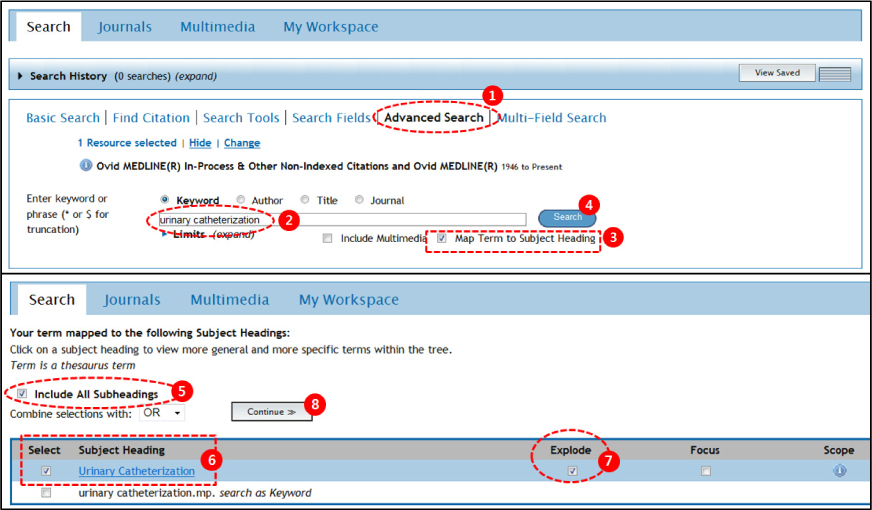

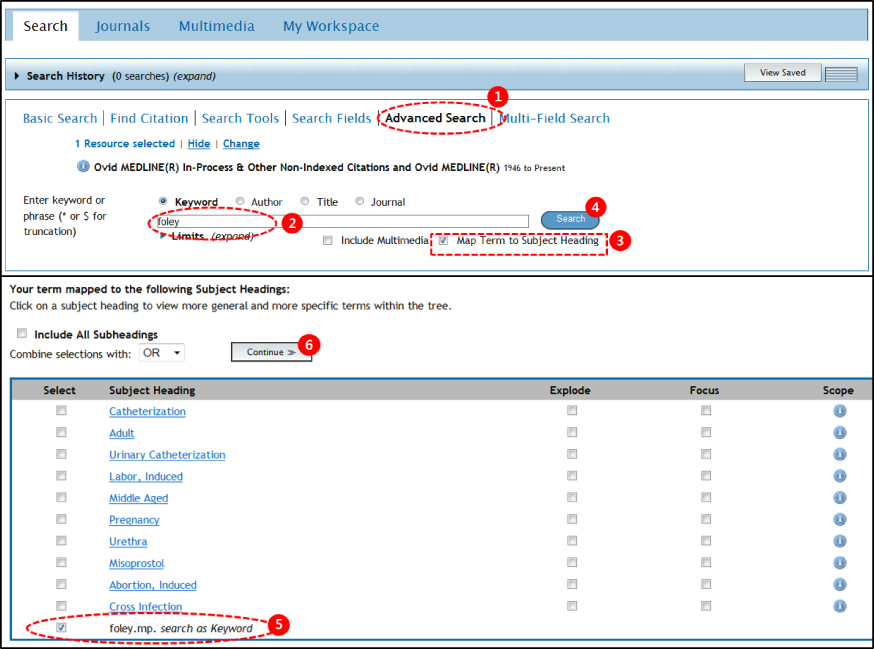

Four different approaches via Ovid MEDLINE were used to search for guidelines on preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Outcomes of this study were the number of records and relevant literature, and the sensitivity and precision of the search methods via Ovid MEDLINE.

RESULTS

The number of retrieved items ranged 23 to 6,005 and that of relevant studies, 5 to 8 of 8. Simple searches resulted in the highest sensitivity of 100.0%. When using MeSH terms and limits feature, the precision was highest (21.7%) among four approaches for literature searches. Simple searches in Ovid had higher sensitivity and lower precision than those in PubMed.

CONCLUSION

Simple searches in Ovid may be inefficient for busy clinicians compared to PubMed. However, to ensure a comprehensive and systematic literature search, using Ovid MEDLINE in addition to PubMed is recommended.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Haig A, Dozier M. BEME guide No. 3: Systematic searching for evidence in medical education-Part 2: Constructing searches. Med Teach. 2003; 25(5):463–484. DOI: 10.1080/01421590310001608667.2. Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Keel M, Cole PA, Kregor PJ. Evidence-based resources and search strategies for orthopedic surgeons. Injury. 2006; 37(4):307–311. DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.01.033.3. Kim YH, Jang KS, Chung KH, Choi JY, Ryu SA, Park HY. An example of systematic searching for guidelines to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections-Part I: Using the PubMed Database. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2014; 20(1):128–143. DOI: 10.11111/jkana.2014.20.1.128.4. Haynes RB, Wilczynski N, McKibbon KA, Walker CJ, Sinclair JC. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound studies in MEDLINE. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994; 1(6):447–458. DOI: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002642.5. Melnyk BM, Finout-Overholt E, editors. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2011.6. Linsey WT, Olin BR. PubMed searches: Overview and strategies for clinicians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013; 28(2):165–176. DOI: 10.1177/0884533613475821.7. Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Chambliss ML, Vinson DC, Stevermer JJ, et al. Obstacles to answering doctors' questions about patient care with evidence: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2002; 324(7339):710.8. Berg A, Fleischer S, Behrens J. Development of two search strategies for literature in MEDLINE-PubMed: Nursing diagnoses in the context of evidence-based nursing. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif. 2005; 16(2):26–32. DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-618X.2005.00006.x.9. Diog GS, Simpson F. Efficient literature searching: A core skill for the practice of evidence-based medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29(12):2119–2127. DOI: 10.1007/s00134-003-1942-5.10. Hopewell S, Clarke MJ, Lefebvre C, Scherer RW. Handsearching versus electronic searching to identify reports of randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; 18(2):MR000001. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.MR000001.pub2.11. Shariff SZ, Bejaimal SA, Sontrop JM, Iansavichus AV, Weir MA, Haynes RB, et al. Searching for medical information online: A survey of Canadian nephrologists. J Nephrol. 2011; 24(6):723–732. DOI: 10.5301/JN.2011.6373.12. De Groote SL. PubMed, Internet Grateful Med, and Ovid: A comparison of three MEDLINE Internet interfaces. Med Ref Serv Q. 2000; 19(4):1–13. DOI: 10.1300/J115v19n04_01.13. Neyt M, Chalon PX. Search MEDLINE for economic evaluations: Tips to translate an OVID strategy into a PubMed one. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013; 31(12):1087–1090. DOI: 10.1007/s40273-013-0103-0.14. Hildebrand AM, Iansavuchus AV, Lee CWC, Haynes RB, Wilczynski NL, Mckibbon KA, et al. Glomerular disease search filters for PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, and Embase: A development and validation study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012; 12:49. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-49.15. Hildebrand AM, Iansavuchus AV, Haynes RB, Wilczynski NL, Mehta RL, Parikh CR, et al. High-performance information search filters for acute kidney injury content in PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE and Embase. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014; 29(4):823–832. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gft531.16. Katchamart W, Faulkner A, Feldman B, Tomlinson G, Bombardier C. PubMed had a higher sensitivity than Ovid-MEDLINE in the search for systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64(7):805–807. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.06.004.17. Coneway LJ, Larson EL. Guidelines to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection: 1980 to 2010. Heart Lung. 2012; 41(3):271–283. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2011.08.001.18. Wong ES. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Am J Infect Control. 1983; 11(1):28–33. DOI: 10.1016/S0196-6553(83)80012-1.19. Pratt RJ, Pellowe C, Loveday HP, Robinson N, Smith GW, Barrett S, et al. The EPIC Project: Developing national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare associated infections. Phase I: Guidelines for preventing hospital-acquired infections. Department of Health(England). J Hosp Infect. 2001; 47:Suppl. S3–S82. DOI: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0886.20. Pratt RJ, Pellowe CM, Wilson JA, Loveday HP, Harper PJ, Jones SRLJ, et al. EPIC 2: National evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect. 2007; 65:Suppl 1. S1–S64. DOI: 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60002-4.21. Tenke P, Kovacs B, Bjerklund Johansen TE, Matsumoto T, Tambyah PA, Naber KG. European and Asian guidelines on management and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008; 31:Suppl 1. S68–S78. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.033.22. Lo E, Nicolle L, Classen D, Arias KM, Podgorny K, Anderson DJ, et al. Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008; 29:Suppl 1. S41–S50. DOI: 10.1086/591066.23. Parker D, Callan L, Harwood J, Thompson D, Webb M-L, Wilde M, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections: Fact sheet. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009; 36(2):156–159. DOI: 10.1097/01.WON.0000347656.94969.99.24. Willson M, Wilde M, Webb M-L, Thompson D, Parker D, Harwood J, et al. Nursing interventions to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection: Part 2: Staff education, monitoring, and care techniques. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009; 36(2):137–154. DOI: 10.1097/01.WON.0000347655.56851.04.25. Parker D, Callan L, Harwood J, Thompson DL, Wilde M, Gray M. Nursing interventions to reduce the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Part 1: Catheter selection. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009; 36(1):23–34. DOI: 10.1097/01.WON.0000345173.05376.3e.26. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 50(5):625–663. DOI: 10.1086/650482.27. Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Agarwal RK, Kuntz G, Pegues DA. Healthcare infection control practices advisory committee. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010; 31(4):319–326. DOI: 10.1086/651091.28. Kim SY, Park JE, Seo HJ, Lee YJ, Jang BH, Son HJ, et al. NECA's guidance for understanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses for intervention. Seoul: National Evidencebased Healthcare Collaborating Agency;2011. p. 19–46.29. University of Texas School of Public Health. Search filters for various databases [Internet]. Texas: The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston;2010. cited 2013 November 16. Available from: http://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/ovid_medline_filters.30. Zhang L, Ajiferuke I, Sampson M. Optimizing search strategies to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6:23. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-23.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- An Example of Systematic Searching for Guidelines to Prevent Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections - Part I: Using the PubMed Database

- Current status of long-term antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary tract infections in children: An antibiotic stewardship challenge

- Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infection

- Management of urinary tract infection in geriatric hospital patients

- Spontaneous Bladder Perforation in a Patient with a Long-Term Intraurethral Catheter