Tuberc Respir Dis.

2009 Jun;66(6):471-476.

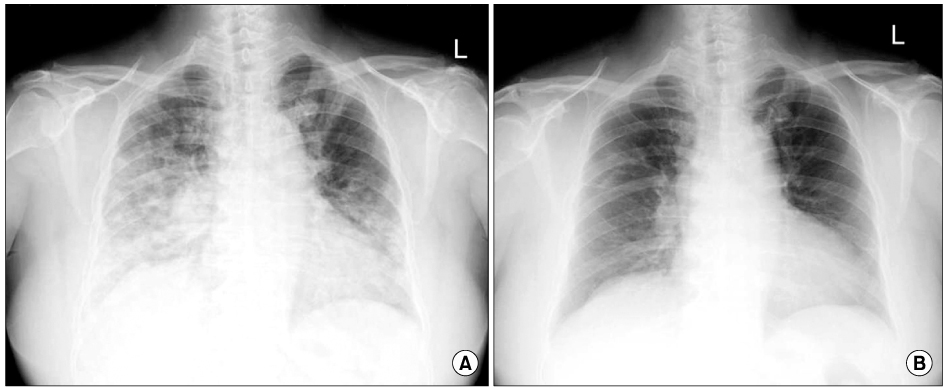

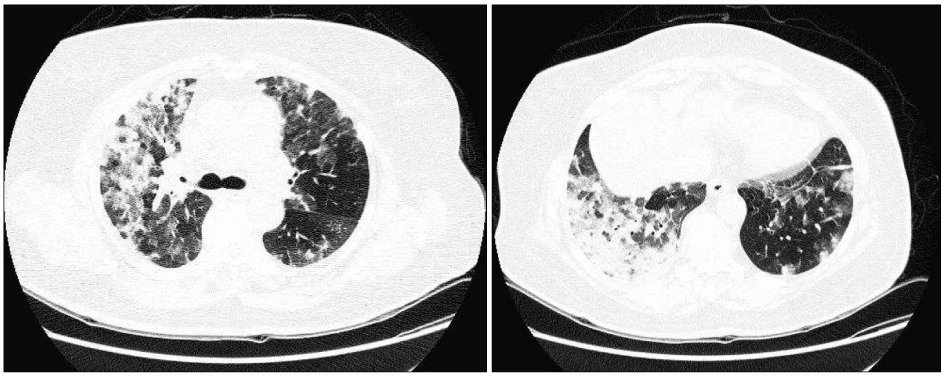

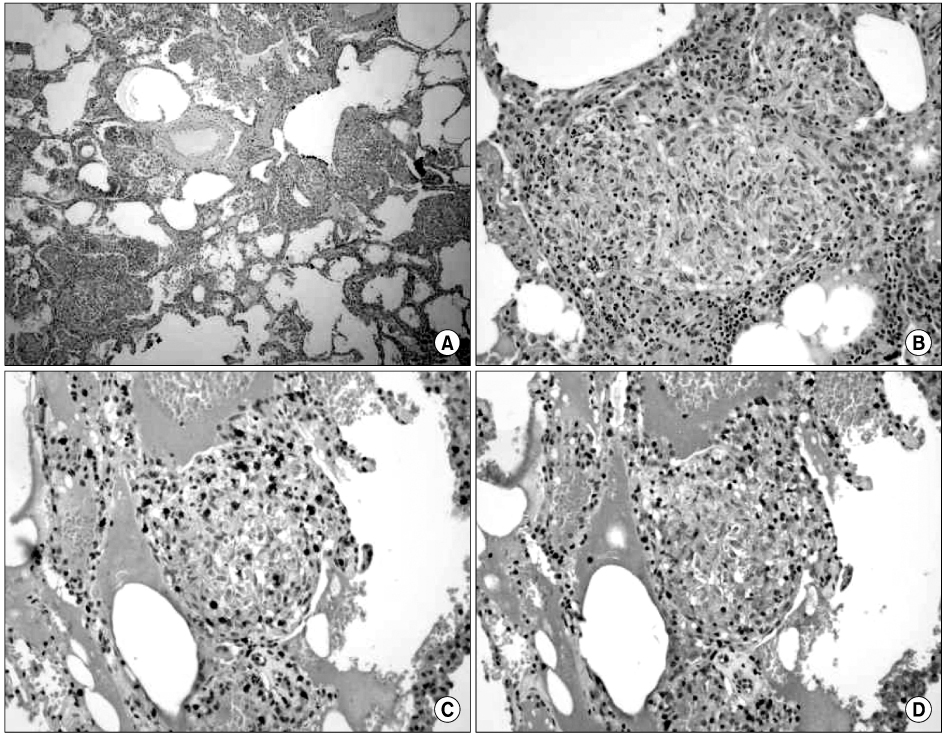

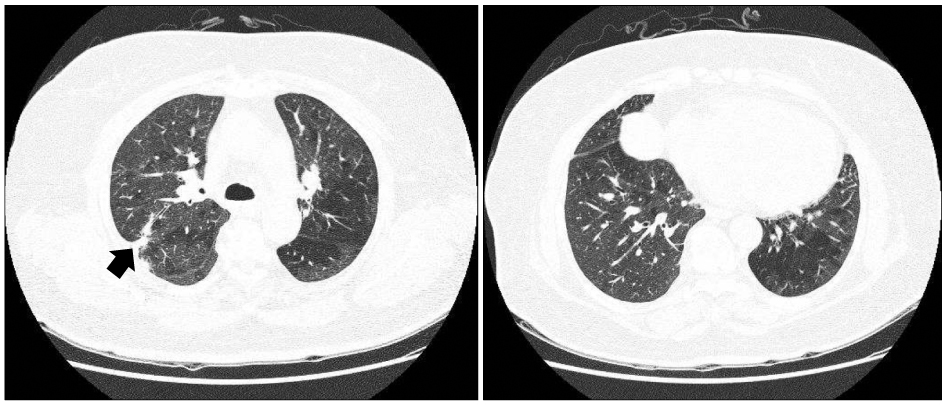

A Case of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Following Placenta Extract Injection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonology and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea. kimdh@dankook.ac.kr

- 2Department of Pathology, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea.

Abstract

- Human placenta contains various kinds of nutritional elements essential for embryonic development. Currently, human placenta extracts are widely overused in Korea to improve certain health conditions (postmenopausal syndrome, liver function, and cosmetic purposes) without scientific evidence that they actually work. The use of placenta extracts should be restricted, due to a lack of systematic research on the therapeutic effectiveness and adverse results from these treatments. While the common adverse effects that have been reported are fever, rash, itching, nausea, vomiting, breast pain, and rare cases of anaphylactic shock, there have been no reports of pulmonary complications such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Recently, we experienced a patient with hypersensitivity pneumonitis following a placenta extract injection. To our knowledge, this is the first case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis associated with placenta extract use.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Park NJ. Safety, efficacy and limitations of medical use of placental extract. J Korean Med Assoc. 2005. 48:1013–1021.2. Shinde V, Dhalwal K, Paradkar AR, Mahadik KR, Kadam SS. Evaluation of in-vitro antioxidant activity of human placental extract. Pharmacologyonline. 2006. 3:172–179.3. Sur TK, Biswas TK, Ali L, Mukherjee B. Anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet aggregation activity of human placental extract. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003. 24:187–192.4. Liu KX, Kato Y, Kaku T, Sugiyama Y. Human placental extract stimulates liver regeneration in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 1998. 21:44–49.5. Kong MH, Lee EJ, Lee SY, Cho SJ, Hong YS, Park SB. Effect of human placental extract on menopausal symptoms, fatigue, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in middle-aged Korean women. Menopause. 2008. 15:296–303.6. Pal P, Mallick S, Mandal SK, Das M, Dutta AK, Datta PK, et al. A human placental extract: in vivo and in vitro assessments of its melanocyte growth and pigment-inducing activities. Int J Dermatol. 2002. 41:760–767.7. Woda BA. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an immunopathology review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008. 132:204–205.8. Glazer CS, Rose CS, Lynch DA. Clinical and radiologic manifestations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging. 2002. 17:261–272.9. Baur X. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (extrinsic allergic alveolitis) induced by isocyanates. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995. 95:1004–1010.10. Timmer SJ, Amundson DE, Malone JD. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis following anthrax vaccination. Chest. 2002. 122:741–745.11. Son CH, Kim HI, Kim KN, Lee KN, Lee CU, Roh MS, et al. Moxifloxacin-associated drug hypersensitivity syndrome with drug-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008. 18:72–73.12. Silva CI, Churg A, Müller NL. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: spectrum of high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007. 188:334–344.13. Kwon KY, Choi WI, Ko SM. Small airway diseases: clinical characteristics and pathological interpretation. Korean J Pathol. 2006. 40:389–398.14. Schuyler M, Cormier Y. The diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest. 1997. 111:534–536.15. Allen MB, Cockwell P, Page RL. Pulmonary and cutaneous vasculitis following hepatitis B vaccination. Thorax. 1993. 48:580–581.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A case of hypersensitivity pneumonitis with positive precipitin antibody to Trichosporon cutaneum

- A Case of Gold Induced Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Diagnosed by Lymphocyte Stimulation Test with Gold

- Effect of Intradermal Injection of Placenta Hydrolysate to Postburn Hyperpigmented Skin

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by oyster mushroom spores

- A Case of Jarisch-Herxheimer Reaction Complicated by Fatal Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in a Patient with Secondary Syphilis