J Breast Cancer.

2016 Jun;19(2):112-121. 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.112.

Breast Cancer Mortality among Asian-American Women in California: Variation according to Ethnicity and Tumor Subtype

- Affiliations

-

- 1Sutter Institute for Medical Research, Sacramento, USA. parisec@sutterhealth.org

- KMID: 2308961

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.112

Abstract

- PURPOSE

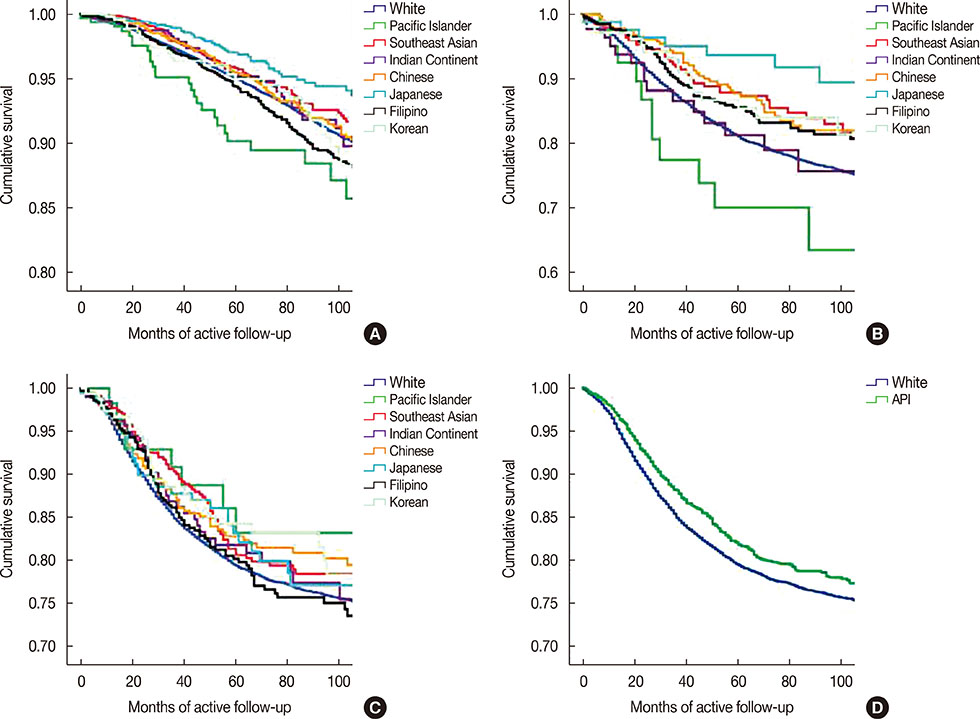

Asian-American women have equal or better breast cancer survival rates than non-Hispanic white women, but many studies use the aggregate term "Asian/Pacific Islander" (API) or consider breast cancer as a single disease. The purpose of this study was to assess the risk of mortality in seven subgroups of Asian-Americans expressing the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) tumor marker subtypes and determine whether the risk of mortality for the aggregate API category is reflective of the risk in all Asian ethnicities.

METHODS

The study included data for 110,120 Asian and white women with stage 1 to 4 first primary invasive breast cancer from the California Cancer Registry. The Asian ethnicities identified were Pacific Islander, Southeast Asian (SEA), Indian Subcontinent, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Korean. A Cox regression analysis was used to compute the risk of breast cancer-specific mortality in seven Asian ethnicities and the combined API category versus white women within each of the ER/PR/HER2 subtypes. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed.

RESULTS

For the ER+/PR+/HER2- subtype, the combined API category showed a 17% (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.91) lower mortality risk. This was true only for SEA (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.91) and Japanese women (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.45-0.81). In the ER+/PR-/HER2- subtype, SEA (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.84) and Filipino women (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51-0.97) had a lower risk of mortality. Japanese (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.25-0.99) and Filipino women (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.94) had a lower HR for the ER-/PR-/HER2+ subtype. For triple-positive, ER+/PR+/HER2+ (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.98) and triple-negative, ER-/PR-/HER2- (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94) subtypes, only the API category showed a lower risk of mortality.

CONCLUSION

Breast cancer-specific mortality among Asian-American women varies according to their specific Asian ethnicity and breast cancer subtype.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000; 406:747–752.

Article2. Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003; 100:8418–8423.

Article3. Parise CA, Bauer KR, Brown MM, Caggiano V. Breast cancer subtypes as defined by the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) among women with invasive breast cancer in California, 1999-2004. Breast J. 2009; 15:593–602.

Article4. Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007; 109:1721–1728.

Article5. Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015; 313:165–173.

Article6. O'Malley CD, Le GM, Glaser SL, Shema SJ, West DW. Socioeconomic status and breast carcinoma survival in four racial/ethnic groups: a population-based study. Cancer. 2003; 97:1303–1311.7. Chuang E, Paul C, Flam A, McCarville K, Forst M, Shin S, et al. Breast cancer subtypes in Asian-Americans differ according to Asian ethnic group. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012; 14:754–758.

Article8. McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS Jr, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007; 57:190–205.

Article9. Gomez SL, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, Chang ET, Keegan TH, Glaser SL. Disparities in breast cancer survival among Asian women by ethnicity and immigrant status: a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100:861–869.

Article10. Trinh QD, Nguyen PL, Leow JJ, Dalela D, Chao GF, Mahal BA, et al. Cancer-specific mortality of Asian Americans diagnosed with cancer: a nationwide population-based assessment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015; 107:djv054.

Article11. Parise C, Caggiano V. Disparities in the risk of the ER/PR/HER2 breast cancer subtypes among Asian Americans in California. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014; 38:556–562.

Article12. Fritz AG. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology: ICD-O. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;2000. p. vi 239.13. California Cancer Registry. Cancer Reporting in California: Abstracting and Coding Procedures for Hospitals. California Cancer Reporting System Standards, Volume I. Sacramento: California Department of Public, Cancer Surveillance and Research Branch;2008.14. Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer;2002.15. Seiffert JE. National Cancer Institute (U.S.). SEER Program: Comparative Staging Guide for Cancer. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute;1993.16. Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Wong YN, Edge SB, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33:2254–2261.

Article17. Purdie CA, Quinlan P, Jordan LB, Ashfield A, Ogston S, Dewar JA, et al. Progesterone receptor expression is an independent prognostic variable in early breast cancer: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2014; 110:565–572.

Article18. American community survey. United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 9th, 2016. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.19. Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R, Morris C, Wright W. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2001; 12:703–711.20. Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Keegan TH, Stroup A. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and Hodgkin's lymphoma incidence in California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005; 14:1441–1447.

Article21. Telli ML, Chang ET, Kurian AW, Keegan TH, McClure LA, Lichtensztajn D, et al. Asian ethnicity and breast cancer subtypes: a study from the California Cancer Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011; 127:471–478.

Article22. Parise CA, Bauer KR, Caggiano V. Disparities in receipt of adjuvant radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery among the cancer-reporting regions of California. Cancer. 2012; 118:2516–2524.

Article23. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk: IBM Corp;2012.24. Bauer KR, Brown M, Creech C, Schlag NC, Caggiano V. Data quality assessment of HER2 in the Sacramento region of the California Cancer Registry. J Reg Manage. 2007; 34:4–7.25. Parise CA, Caggiano V. The influence of socioeconomic status on racial/ethnic disparities among the ER/PR/HER2 breast cancer subtypes. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2015; 2015:813456.

Article26. Torre LA, Sauer AM, Chen MS Jr, Kagawa-Singer M, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for Asian Americans, native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, 2016: converging incidence in males and females. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016; 66:182–202.

Article27. Parise CA, Caggiano V. Disparities in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: risk of mortality of breast cancer patients in the California Cancer Registry, 2000-2010. BMC Cancer. 2013; 13:449.

Article28. Gomez SL, Shariff-Marco S, DeRouen M, Keegan TH, Yen IH, Mujahid M, et al. The impact of neighborhood social and built environment factors across the cancer continuum: current research, methodological considerations, and future directions. Cancer. 2015; 121:2314–2330.

Article29. Ma H, Bernstein L, Pike MC, Ursin G. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2006; 8:R43.

Article30. Sieri S, Chiodini P, Agnoli C, Pala V, Berrino F, Trichopoulou A, et al. Dietary fat intake and development of specific breast cancer subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014; 106:dju068.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Experiences of Korean-American Women with High Risk Hereditary Breast Cancer

- Breast Cancer Risk Prediction in Korean Women: Review and Perspectives on Personalized Breast Cancer Screening

- Breast Cancer Screening with MRI

- A Comparative Study of Korean and Korean-American Women in Their Health Beliefs related to Breast Cancer and the Performance of Breast Self-Examination

- Contrasting income-based inequalities in incidence and mortality of breast cancer in Korea, 2006-2015