Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2014 Sep;20(3):185-194. 10.4069/kjwhn.2014.20.3.185.

Comparison of Health-related Behaviors in Pregnant Women and Breast-feeding Mothers vs Non-pregnant Women

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Nursing, Daewon University College, Jecheon, Korea.

- 2Department of Health Administration, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea. parklove5004@naver.com

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea.

- KMID: 2307929

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2014.20.3.185

Abstract

- PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to assess health-related behavior of pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers by investigating relevant risk factors.

METHODS

Data of 10,396 women (age 19 to 49 years) from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey report from 2007 to 2012 was used to analyze factors associated with health-related behavior. The subjects were divided into pregnant women; breastfeeding mothers; and non-pregnant women. Bottle feeding mothers were excluded.

RESULTS

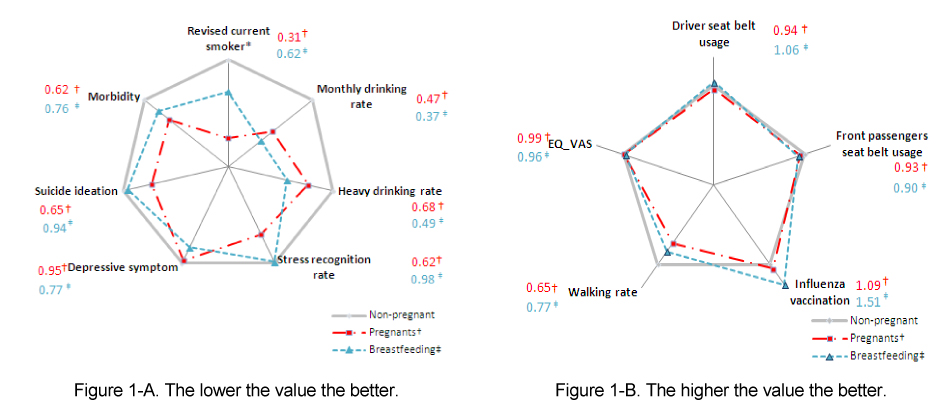

Current smoking rate including self-reported smoker and/or positive cotinine urine test were lower for pregnant or breast-feeding group than non-pregnant group. Heavy-drinking was not different among groups while monthly drinking rate was higher in non-pregnant group. Rate of stress recognition was lower in pregnant and breast-feeding group than non-pregnant group. Rate of experience for depressive symptoms and rate of suicidal ideation were not different among groups.

CONCLUSION

Pregnant women and breast-feeding mothers maintain a good pattern of health-related behavior compared to non-pregnant women. However, substantial proportion of pregnant women and breast-feeding mothers continue to drink and smoke. This shows the need for a plan that will modify health-related behavior.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Comparison of Effects of Oral Health Program and Walking Exercise Program on Health Outcomes for Pregnant Women

Hae-jin Park, Haejung Lee

J Korean Acad Nurs. 2018;48(5):506-520. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2018.48.5.506.Differences in Drinking Scores according to Stress and Depression in Unmarried Women

Hyo Jung Kim, Chae Weon Chung

Perspect Nurs Sci. 2016;13(1):10-16. doi: 10.16952/pns.2016.13.1.10.

Reference

-

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). Korea health statistics 2011: Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANESV-2). Chengju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2012. cited 2013 June 10. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do.2. Baraona E, Abittan CS, Dohmen K, Moretti M, Pozzato G, Chayes ZW, et al. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001; 25(4):502–507.

Article3. Jones KL. The effects of alcohol on fetal development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2011; 93(1):3–11.

Article4. Do EY, Hong YR. Factors affecting pregnant women's drinking. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2011; 31(3):284–307.5. Yeom GJ, Choi SY, Kim IO. The influencing factors on alcohol use during pregnancy. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2011; 15(1):71–81.6. Mallard SR, Conner JL, Houghton LA. Maternal factors associated with heavy periconceptional alcohol intake and drinking following pregnancy recognition: A post-partum survey of New Zealand women. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013; 32(4):389–397.

Article7. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Effects of alcohol on a fetus [Internet]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services;2007. cited 2013 May 10. Available from: http://www.fascenter.samhsa.gov.8. Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. The transfer of alcohol to human milk. Effects on flavor and the infant's behavior. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325(14):981–985.9. Koren G. Drinking alcohol while breastfeeding. Will it harm my baby? Can Fam Physician. 2002; 48:39–41.10. Kim JY. Actual condition of smoking during pregnancy in 2003 and 2010 [master's thesis]. Asan: Soonchunhyang University;2011.11. Langhammer A, Johnsen R, Holmen J, Gulsvik A, Bjermer L. Cigarette smoking gives more respiratory symptoms among women than among men. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000; 54(12):917–922.12. Lee JJ. The effects of maternal smoking in pregnancy. Korean J Perinatol. 2002; 13(4):357–365.13. Jo DI. Pregnant women and smoking. J Korean Assoc Health Promot. 2003; 27(5):10–11.14. Lee BE, Hong YC, Park HS, Lee JT, Kim JY, Kim YJ, et al. Maternal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and pregnancy outcome (low birth weight or preterm baby) in prospective cohort study. Korean J Prev Med. 2003; 36(2):117–124.15. Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJ, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005; 29(2):237–258.

Article16. Glover V. Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; What needs to be done. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014; 28(1):25–35.

Article17. Chandler KD, Bell AW. Effects of maternal exercise on fetal and maternal respiration and nutrient metabolism in the pregnant ewe. J Dev Physiol. 1981; 3(3):161–176.18. Melzer K, Schutz Y, Boulvain M, Kayser B. Physical activity and pregnancy: Cardiovascular adaptations, recommendations and pregnancy outcomes. Sports Med. 2010; 40(6):493–507.19. Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Yang X, Frosch D, Nahom D, Jarvik ME, et al. Smoking cessation in methadone maintenance. Addiction. 2002; 97(10):1317–1328.

Article20. Ebert LM, Fahy K. Why do women continue to smoke in pregnancy? Women Birth. 2007; 20(4):161–168.

Article21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use among pregnant and non pregnant women of childbearing age-United States, 1991-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58(19):529–532.22. Breslow RA, Falk DE, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Alcohol consumption among breastfeeding women. Breastfeed Med. 2007; 2(3):152–157.

Article23. Ernhart CB, Morrow-Tlucak M, Sokol RJ. Underreporting of alcohol use in pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988; 12(4):506–511.

Article24. Department of Health (DOH). Smoking kills: A white paper on tobacco [Internet]. London: Department of Health;1998. cited 2013 May 25. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-white-paper-on-tobacco.25. West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: An update. Thorax. 2000; 55(12):987–999.

Article26. Ethen MK, Ramadhani TA, Scheuerle AE, Canfield MA, Wyszynski DF, Druschel CM, et al. Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J. 2009; 13(2):274–285.

Article27. Johnson HC, Pring DW. Car seatbelts in pregnancy: The practice and knowledge of pregnant women remain causes for concern. BJOG. 2000; 107(5):644–647.

Article28. Kim YJ, Lee SS. The relation of maternal stress with nutrients intake and pregnancy outcome in pregnant women. Korean J Nutr. 2008; 41(8):776–785.29. Kim Y, Chung CW. Factors of prenatal depression by stress-vulnerability and stress-coping models. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2014; 20(1):38–47.

Article30. Kang S, Chung M. The relationship between pregnant woman's stress, temperature and maternal-fetal attachment. Korean J Hum Ecol. 2012; 21(2):213–223.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Overall health and drinking behavior among pregnant and breastfeeding women in Korea

- Analysis of pregnant and breast-feeding women’s unmet healthcare needs

- Breast-feeding & Breast-feeding Health Behavior among first-time mothers

- Effects of Breastfeeding Education Prgoram on the Promotion of Mothers's Feeding Compliance

- Attitudes of Pregnant women's husbands to Breast Feeding