Korean J Neurotrauma.

2014 Oct;10(2):60-65. 10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.60.

Midline Splitting Cervical Laminoplasty Using Allogeneic Bone Spacers: Comparison of Fusion Rates between Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy and Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurological Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. srjeon@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 2256232

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.60

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To analyze factors associated with fusion using allogeneic bone spacers for midline splitting cervical laminoplasty (MSCL).

METHODS

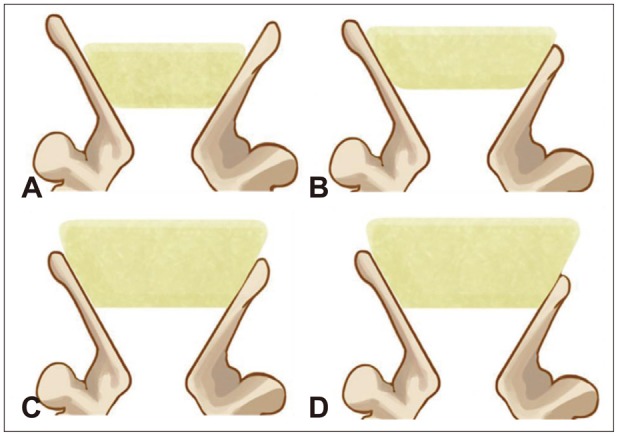

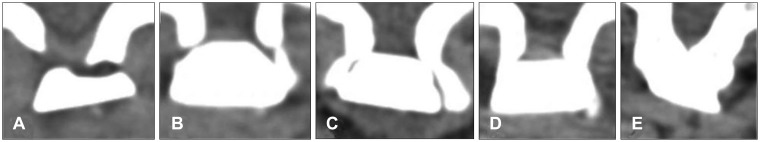

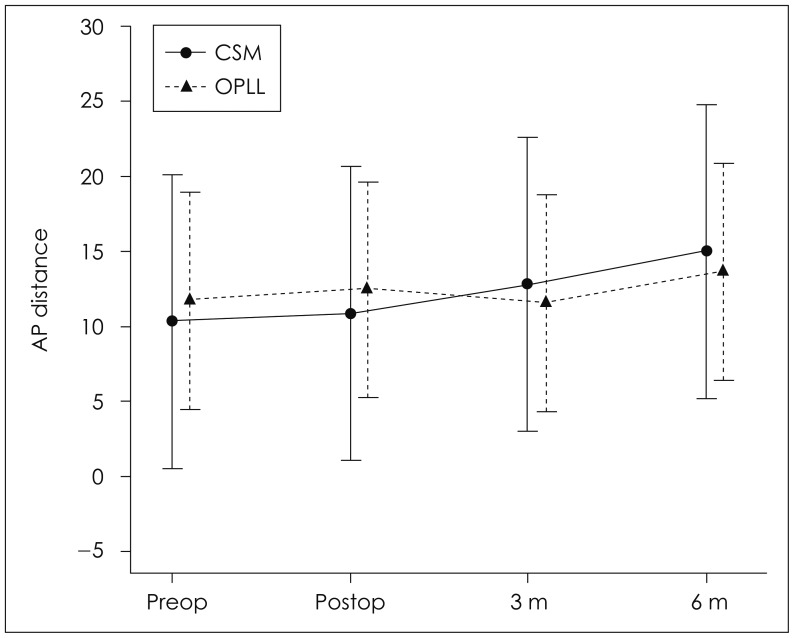

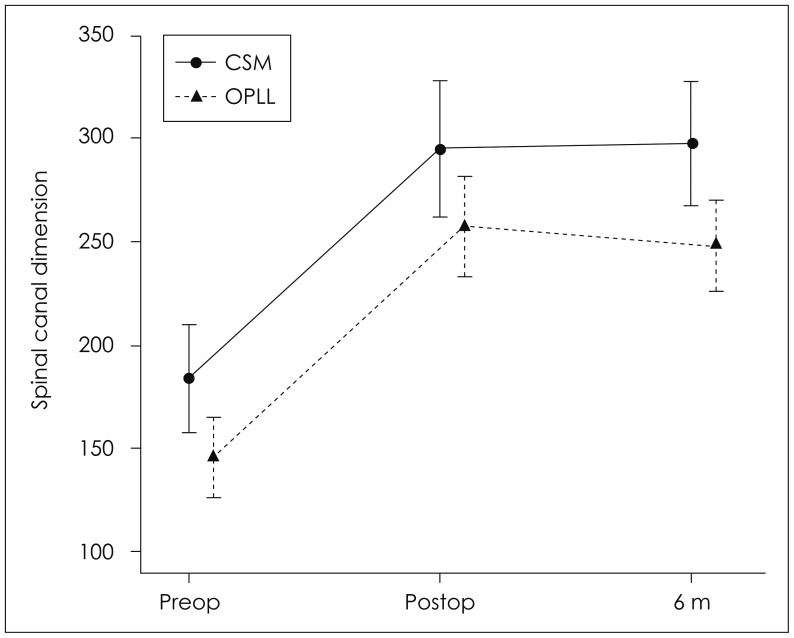

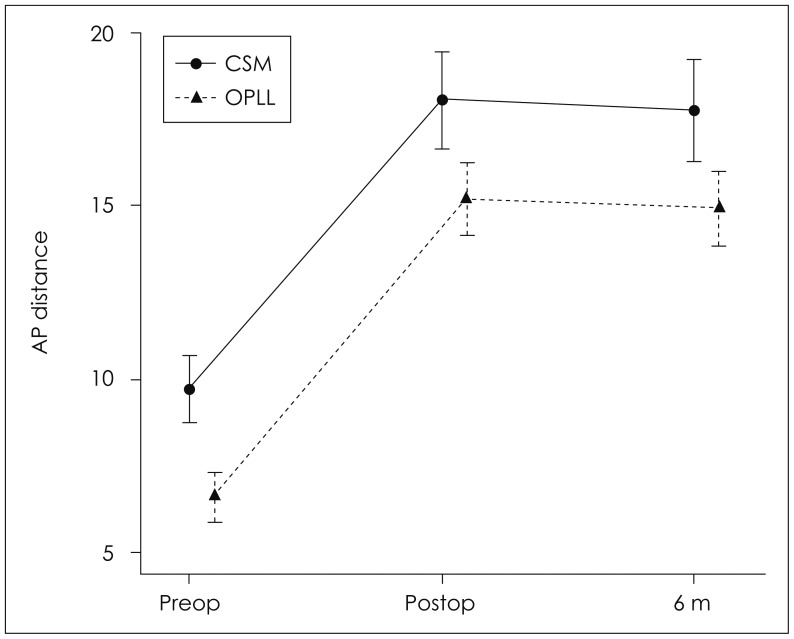

During April 2012 and September 2013, seventeen patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) or ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) underwent MSCL with allogeneic bone spacers by a single surgeon. Mean follow up periods was 11.3 months (range, 6-19 months). Clinical outcomes were evaluated by the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scores at preoperative and postoperative 6 months. Simple cervical X-rays were taken preoperatively, immediate postoperatively, 3, and 6 months after operation. Computed tomography (CT) scans were performed preoperatively, immediate postoperatively and 6 months postoperatively. The differences between two diseases were analyzed on cervical lordosis, canal dimension, anteroposterior (AP) distance, fusion between lamina and allogeneic bone spacer and affecting factors of fusion.

RESULTS

All surgeries were performed on 59 levels. There were no significant differences on the changes of lordosis (p=0.602), canal dimension (p=0.554), and AP distance (p=0.924) as well as JOA scores (p=0.257) between CSM and OPLL groups. Overall fusion rate was 51%. Multivariate analysis on the factor for the fusion rates between lamina and spacers showed that the immediate postoperative contact status between lamina and spacers in CT as significant factor of fusion (p=0.024).

CONCLUSION

The present study suggests that CSM and OPLL did not show difference of surgical outcome in MSCL using allogeneic bone spacer. In addition, we should consider the contact status between lamina and bone spacer for the better fusion rates for this surgery.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Investigation of Symptomatic Unstable Changes of Non-Fused Component in the Mixed-Type Cervical Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Using Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Case Report

Yoon Hee Choo, Sang Woo Kim, Ikchan Jeon

Korean J Neurotrauma. 2018;14(2):164-168. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2018.14.2.164.

Reference

-

1. Fujiwara K, Yonenobu K, Ebara S, Yamashita K, Ono K. The prognosis of surgery for cervical compression myelopathy. An analysis of the factors involved. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989; 71:393–398. PMID: 2722928.

Article2. Hirabayashi S, Kumano K. Contact of hydroxyapatite spacers with split spinous processes in double-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy. J Orthop Sci. 1999; 4:264–268. PMID: 10436273.

Article3. Iguchi T, Kanemura A, Kurihara A, Kasahara K, Yoshiya S, Doita M, et al. Cervical laminoplasty: evaluation of bone bonding of a high porosity hydroxyapatite spacer. J Neurosurg. 2003; 98(2 Suppl):137–142. PMID: 12650397.

Article4. Iwasaki M, Kawaguchi Y, Kimura T, Yonenobu K. Long-term results of expansive laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: more than 10 years follow up. J Neurosurg. 2002; 96(2 Suppl):180–189. PMID: 12450281.

Article5. Kimura I, Shingu H, Nasu Y. Long-term follow-up of cervical spondylotic myelopathy treated by canal-expansive laminoplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995; 77:956–961. PMID: 7593114.

Article6. Miller LE, Block JE. Safety and effectiveness of bone allografts in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011; 36:2045–2050. PMID: 21304437.

Article7. Moreira-Gonzalez A, Jackson IT, Miyawaki T, Barakat K, DiNick V. Clinical outcome in cranioplasty: critical review in long-term follow-up. J Craniofac Surg. 2003; 14:144–153. PMID: 12621283.

Article8. Nagashima T, Ohshima Y, Takeuchi H. [Osteoconduction in porous hydroxyapatite ceramics grafted into the defect of the lamina in experimental expansive open-door laminoplasty in the spinal canal]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995; 69:222–230. PMID: 7782659.9. Park JH, Jeon SR. Midline-splitting open door laminoplasty using hydroxyapatite spacers: comparison between two different shaped spacers. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012; 52:27–31. PMID: 22993674.10. Putzier M, Strube P, Funk JF, Gross C, Mönig HJ, Perka C, et al. Allogenic versus autologous cancellous bone in lumbar segmental spondylodesis: a randomized prospective study. Eur Spine J. 2009; 18:687–695. PMID: 19148687.

Article11. Russell JL, Block JE. Surgical harvesting of bone graft from the ilium: point of view. Med Hypotheses. 2000; 55:474–479. PMID: 11090293.

Article12. Seo DK, Park JH, Jeon SR. The comparison of clinical and radiological long-term outcomes between ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament and cervical spondylotic myelopathy after modified midline splitting cervical laminoplasty. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2012; 8:26–31.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Comparison of Clinical and Radiological Long-Term Outcomes between Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament and Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy after Modified Midline Splitting Cervical Laminoplasty

- Does Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Progress after Fusion?

- A Comparison of Implants Used in Double Door Laminoplasty : Allogeneic Bone Spacer versus Hydroxyapatite Spacer

- Anterior Decompression and Fusion for the Treatment of Cervical Myelopathy Caused by Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament: A Narrative Review

- Cervical Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament in X-Linked Hypophosphatemic Rickets Revealing Homogeneously Increased Vertebral Bone Density