Korean Circ J.

2011 Jul;41(7):349-353. 10.4070/kcj.2011.41.7.349.

The Significance of the J-Curve in Hypertension and Coronary Artery Diseases

- Affiliations

-

- 1Cardiovascular Center, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea. packcg@kumc.or.kr

- KMID: 2225096

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2011.41.7.349

Abstract

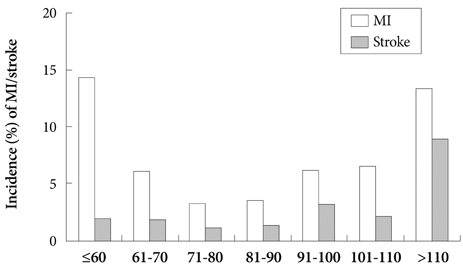

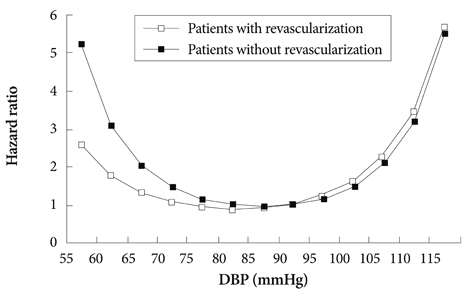

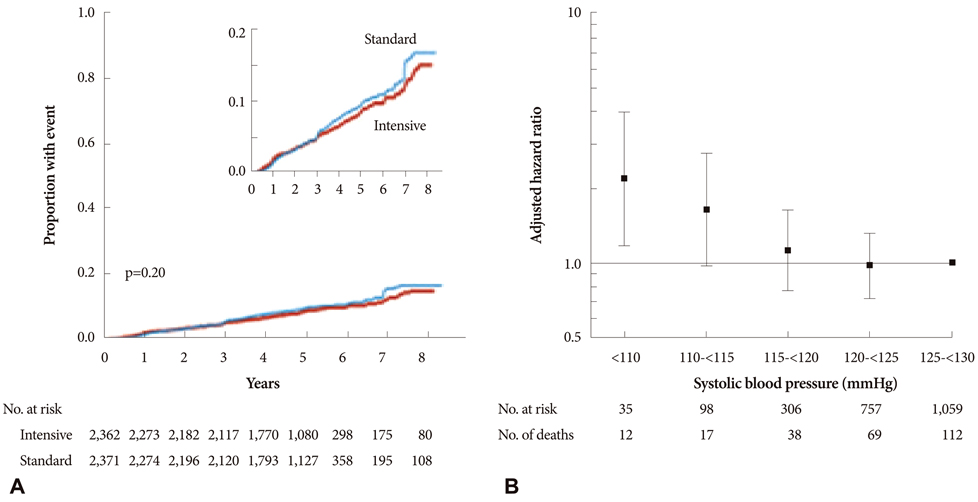

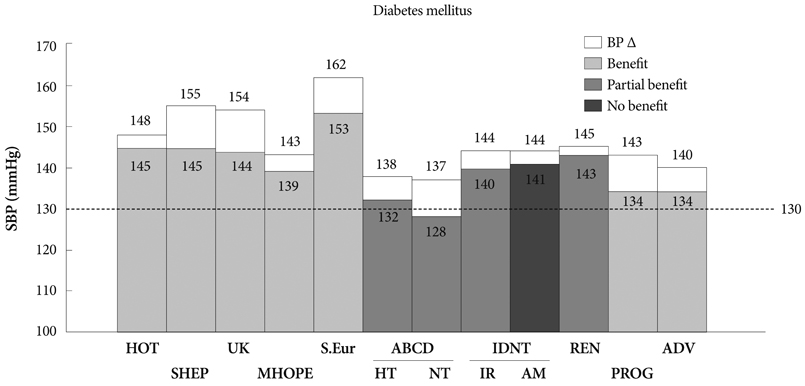

- The J-curve effect describes an inverse relation between low blood pressure (BP) and cardiovascular complications. This effect is more pronounced in patients with preexisting coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension or left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). The recent large clinical outcomes trials have observed a J-curve effect between a diastolic BP of 70-80 mmHg as well as a systolic BP <130 mmHg. The J-curve phenomenon does not appear in stroke or renal disease. This is because the coronary arteries are perfused during diastole, but the cerebral and renal perfusion mainly occurs in systole. Therefore, caution should be taken to maintain the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) at minimum of 70 mmHg and possibly to maintain the DBP between 80-85 mmHg in patients with severe LVH, CAD or vascular diseases. BP control in high-risk elderly patients should be carefully done as undergoing aggressive therapy to lower the systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg can cause cardiovascular complications due to the severely reduced DBP and increased pulse pressure.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Frank E. Deutsches archiv fur klin. Medizin. 1911. 103:397–412.2. White P. Heart Disease. 1931. 1st ed. New York: McMillan.3. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996. 276:1328–1331.4. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002. 360:1903–1913.5. Stewart IM. Relation of reduction in pressure to first myocardial infarction in patients receiving treatment for severe hypertension. Lancet. 1979. 1:861–865.6. Cruickshank JM, Thorp JM, Zacharias EJ. Benefits and potential harm of lowering high blood pressure. Lancet. 1987. 1:581–584.7. Farnett L, Muldrow CD, Linn WD, Lucey CR, Tuley MR. The J-curve phenomenon and the treatment of hypertension: is there a point beyond which pressure reduction is dangerous? JAMA. 1991. 265:489–495.8. Bellamy RF. Diastolic coronary artery pressure flow relations in the dog. Circ Res. 1978. 43:92–101.9. Pijls NHJ, De Bruyne B. Pitfalls in coronary pressure measurements. Coronary pressure. 1997. Dortrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers;105–108.10. Harrison DG, Florentine MS, Brooks LA, Cooper SM, Marcus ML. The effect of hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy on the lower range of coronary autoregulation. Circulation. 1988. 77:1108–1115.11. Polese A, De Cesare N, Montorsi P, et al. Upward shift of the lower range of coronary flow autoregulation in hypertensive patients with hypertrophy of the left ventricle. Circulation. 1991. 83:845–853.12. Hakala SM, Tilvis RS. Determinants and significance of declining blood pressure in old age: a prospective birth cohort study. Eur Heart J. 1998. 19:1872–1878.13. Langer RD, Criqui MH, Barrett-Connor EL, Klauber MR, Ganiats TG. Blood pressure change and survival after age 75. Hypertension. 1993. 22:551–559.14. Tervahauta M, Pekkanen J, Enlund H, Nissinen A. Change in blood pressure and 5-year risk of coronary heart disease among elderly men: the Finnish cohorts of the Seven Countries Study. J Hypertens. 1994. 12:1183–1189.15. Satish S, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Clinical significance of falling blood pressure among older adults. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001. 54:961–967.16. Somes GW, Pahor M, Shorr RI, Cushman WC, Applegate WB. The role of diastolic blood pressure when treating isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1999. 159:2004–2009.17. Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L, et al. On-treatment diastolic blood pressure and prognosis in systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2007. 167:1884–1891.18. Messerli FH, Mancia G, Conti CR, et al. Dogma disputed: can aggressively lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease be dangerous? Ann Intern Med. 2006. 144:884–893.19. Haller H, Ito S, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Olmesartan for the delay or prevention of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2011. 364:907–917.20. Bangalore S, Messerli FH, Wun CC, et al. J-curve revisited: an analysis of blood pressure and cardiovascular events in the Treating to New Targets (TNT) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2010. 31:2897–2908.21. Sleight P, Redon J, Verdecchia P, et al. Prognostic value of blood pressure in patients with high vascular risk in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial Study. J Hypertens. 2009. 27:1360–1369.22. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trial: HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998. 351:1755–1762.23. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010. 362:1575–1585.24. Flack JM, Neaton J, Grimm R Jr, et al. Blood pressure and mortality among men with prior myocardial infarction: Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Circulation. 1995. 92:2437–2445.25. Glynn RJ, L'Italien GJ, Sesso HD, Jackson EA, Buring JE. Development of predictive models for long-term cardiovascular risk associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Hypertension. 2002. 39:105–110.26. Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, et al. Association between blood pressure level and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2001. 161:1183–1192.27. Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009. 27:2121–2158.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Retraction: The Significance of the J-Curve in Hypertension and Coronary Artery Diseases

- Coronary Stent Fracture in a Patient with an Atrial Septal Defect and Severe Pulmonary Hypertension

- Two Cases of Anomalous Origin of Coronary Artery

- The Evaluation of Coronary Artery Stenosis by Exercise-Induced Negative U Wave

- Carotid ultrasound in patients with coronary artery disease