J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2014 Mar;55(3):396-401. 10.3341/jkos.2014.55.3.396.

Characteristics of the Gray Optic Disc Crescent and Associated Factors

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. yongykim@korea.ac.kr

- KMID: 2218269

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2014.55.3.396

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate the characteristics of the gray optic disc crescent and associated factors.

METHODS

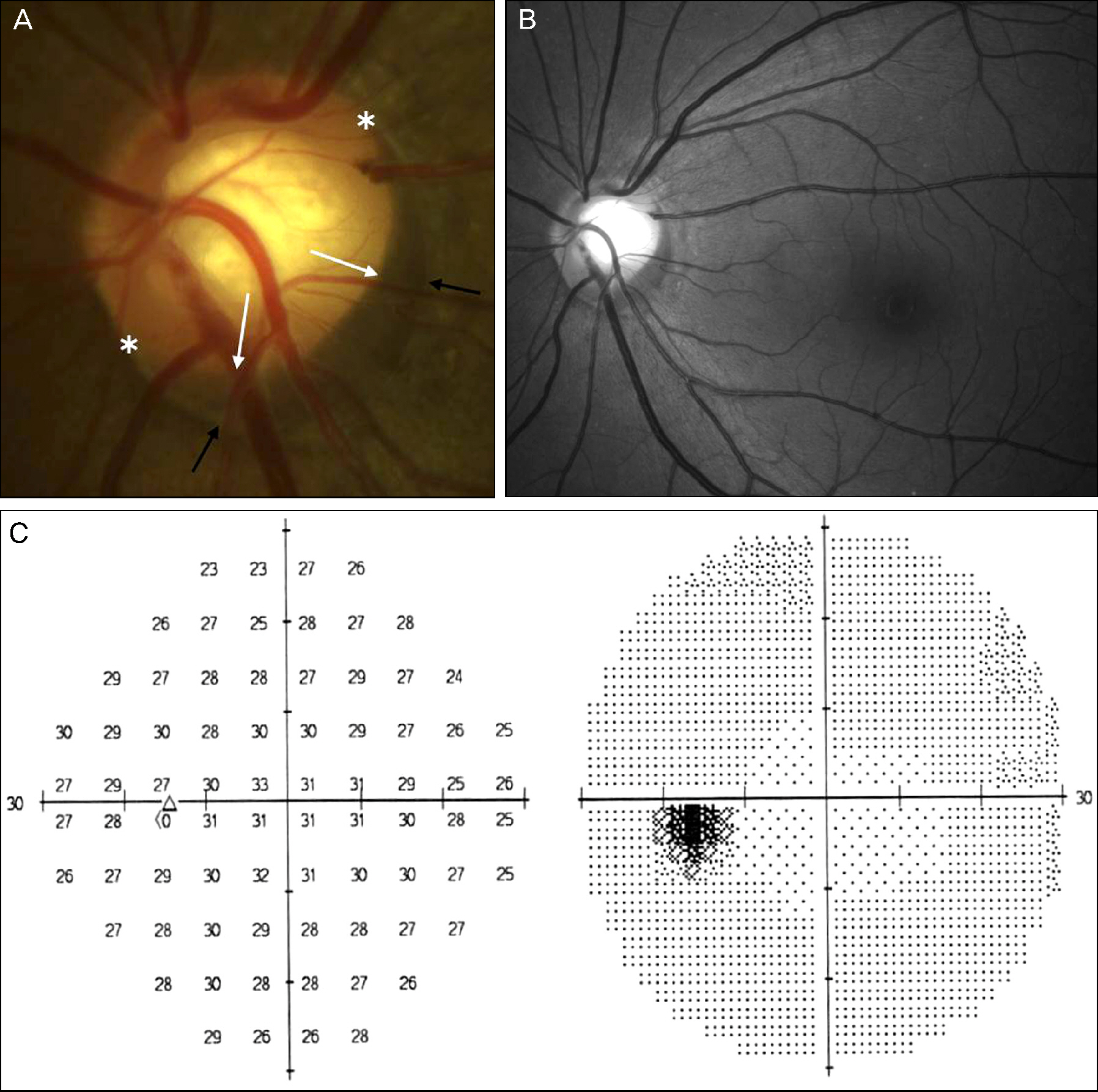

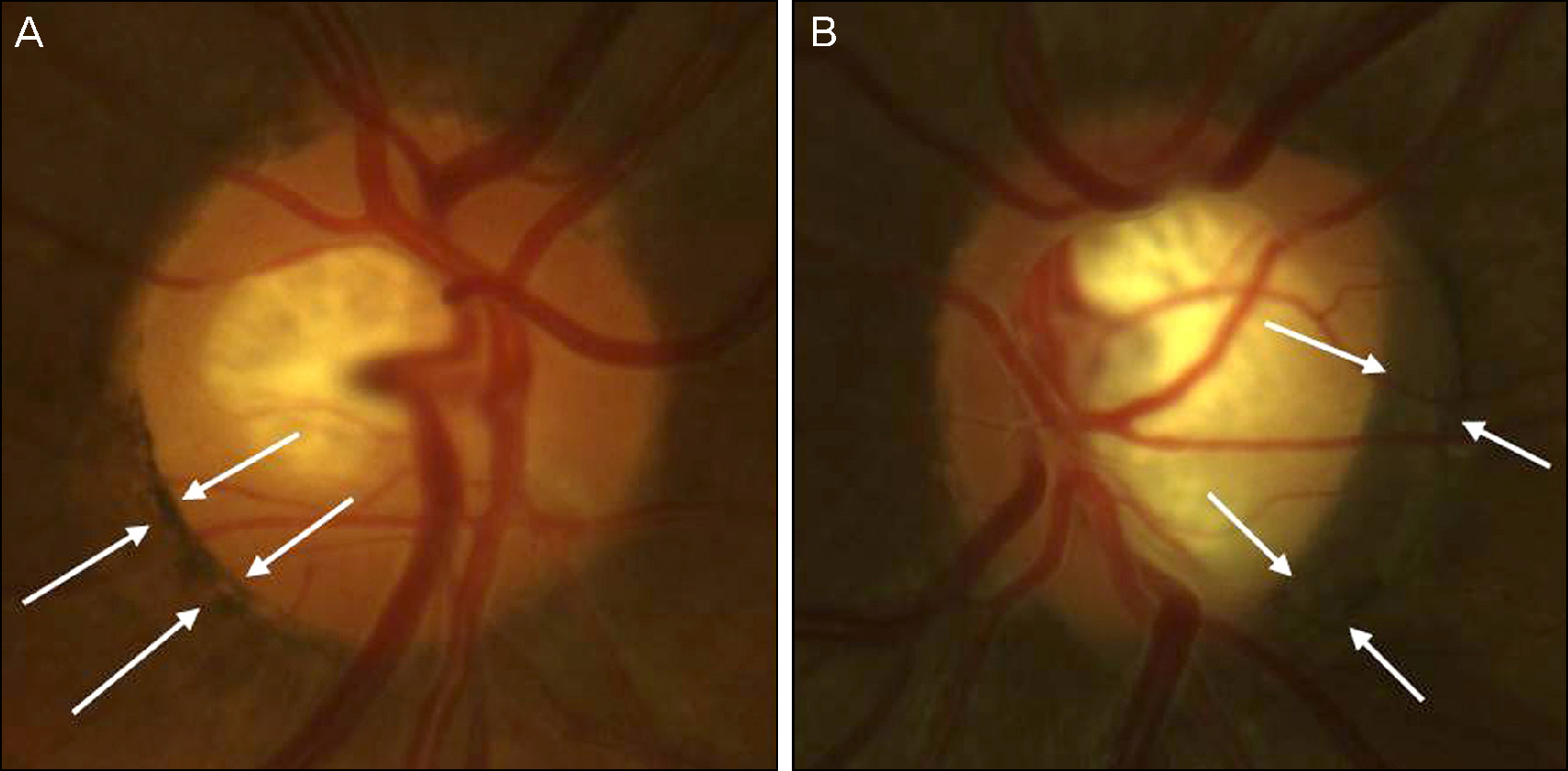

We retrospectively reviewed stereo fundus photographs of 590 glaucoma patients and 273 non-glaucoma patients. An experienced investigator evaluated the presence or absence of the gray crescent (a crescent-shaped, slate-gray pigmentation on the periphery of the neuroretinal rim) which is entirely inside the scleral crescent. Correlations with age, gender, refractive error, disc diameters, and the presence of glaucoma or peripapillary atrophy were also analyzed.

RESULTS

Out of 863 patients, the gray crescent was observed in 166 patients and was found in 19.0% of glaucoma patients and 19.8% of non-glaucoma patients. The gray crescent was most often located temporally (30.1%) and most frequently occurred within only 1 quadrant (63.9%). The prevalence of the gray crescent was not correlated with refractive error (p = 0.61) or the occurrence of glaucomatous optic neuropathy (p = 0.25), but was significantly related to peripapillary atrophy (p < 0.001) and the horizontal diameter of the optic disc (p = 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

The gray optic disc crescent is a common finding within a glaucomatous or non-glaucomatous eye and factors significantly related to occurrence of the gray crescent include peripapillary atrophy and the horizontal diameter of the optic disc. Patients with gray crescent require special attention when the optic disc is examined.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Shields MB. Gray crescent in the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980; 89:238–44.

Article2. Higginbotham L, Shafranov G, Shields MB. Gray optic disc crescent influence of ethnicith in a glaucoma population. J Glaucoma. 2007; 16:572–6.3. Jonsson O, Damji KF, Jonasson F, et al. Epidemiology of the optic nerve gray crescent in the Reykjavik Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89:36–9.4. Fournier AV, Damji KF, Epstein DL, Pollock SC. Disc excavation in dominant optic atrophy: differentiation from normal tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:1595–602.5. Araie M, Sekine M, Suzuki Y, Koseki N. Factors contributing to the progression of visual field damage in eyes with normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101:1440–4.

Article6. Jonas JB, Nguyen XN, Gusek GC, Naumann GO. Parapapillary chorioretinal atrophy in normal and glaucoma eyes. I. Morphometric data. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989; 30:908–18.7. Jonas JB, Naumann GO. Parapapillary chorioretinal atrophy in normal and glaucoma eyes. II. Correlations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989; 30:1604–11.8. Park KH, Tomita G, Liou SY, Kitazawa Y. Correlation between peripapillary atrophy and optic nerve damage in normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:1899–906.

Article9. Jonas JB. Clinical implications of peripapillary atrophy in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2005; 16:84–8.

Article10. Teng CC, De Moraes CG, Prata TS, et al. The region of largest β-zone parapapillary atrophy area predicts the location of most rapid visual field progression. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:2409–13.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Study on Interrelationship of the Refractive Error and the Ocular Fundus Findings

- Comparison of Optic Disc Appearance in Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and Optic neuritis

- The Effect of Optic Disc Size or Age on Evaluation of Optic Disc Parameters

- A Case of Optic Disc Pit

- Optic Disc Hamartoma Combined with Optic Neuritis