J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2014 May;55(5):755-760. 10.3341/jkos.2014.55.5.755.

Two Cases of Actinomyces Infection in a Hydroxyapatite Orbital Implant with a Motility Peg

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ydkimoph@skku.edu

- KMID: 2218099

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2014.55.5.755

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To report 2 cases of Actinomyces infection in a hydroxyapatite orbital implant with a motility peg.

CASE SUMMARY

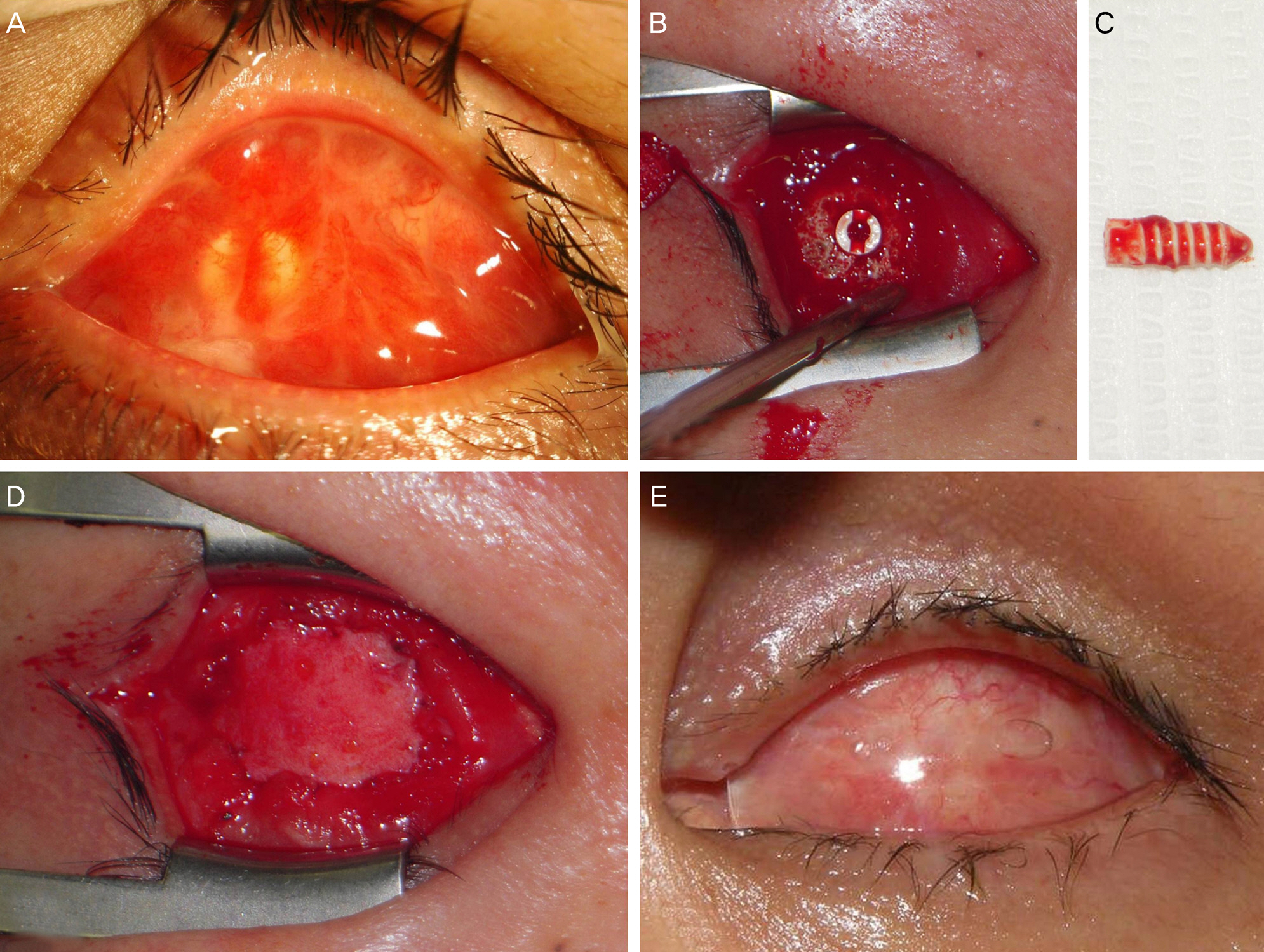

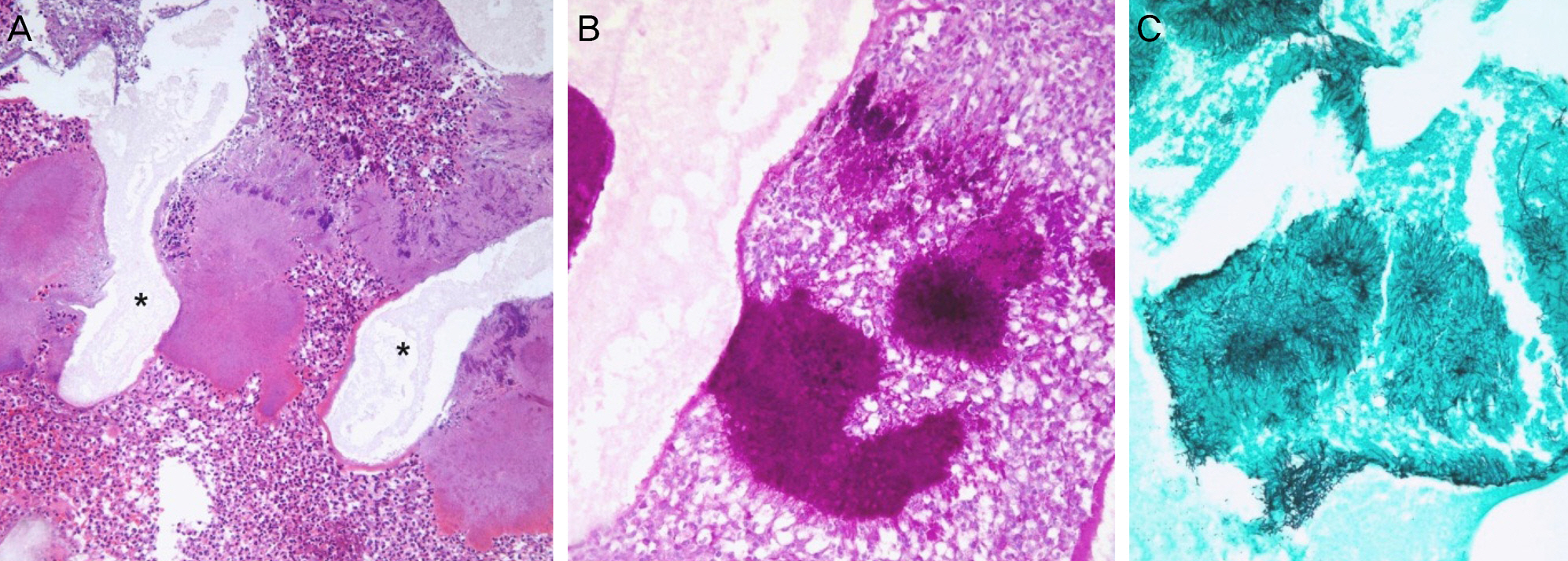

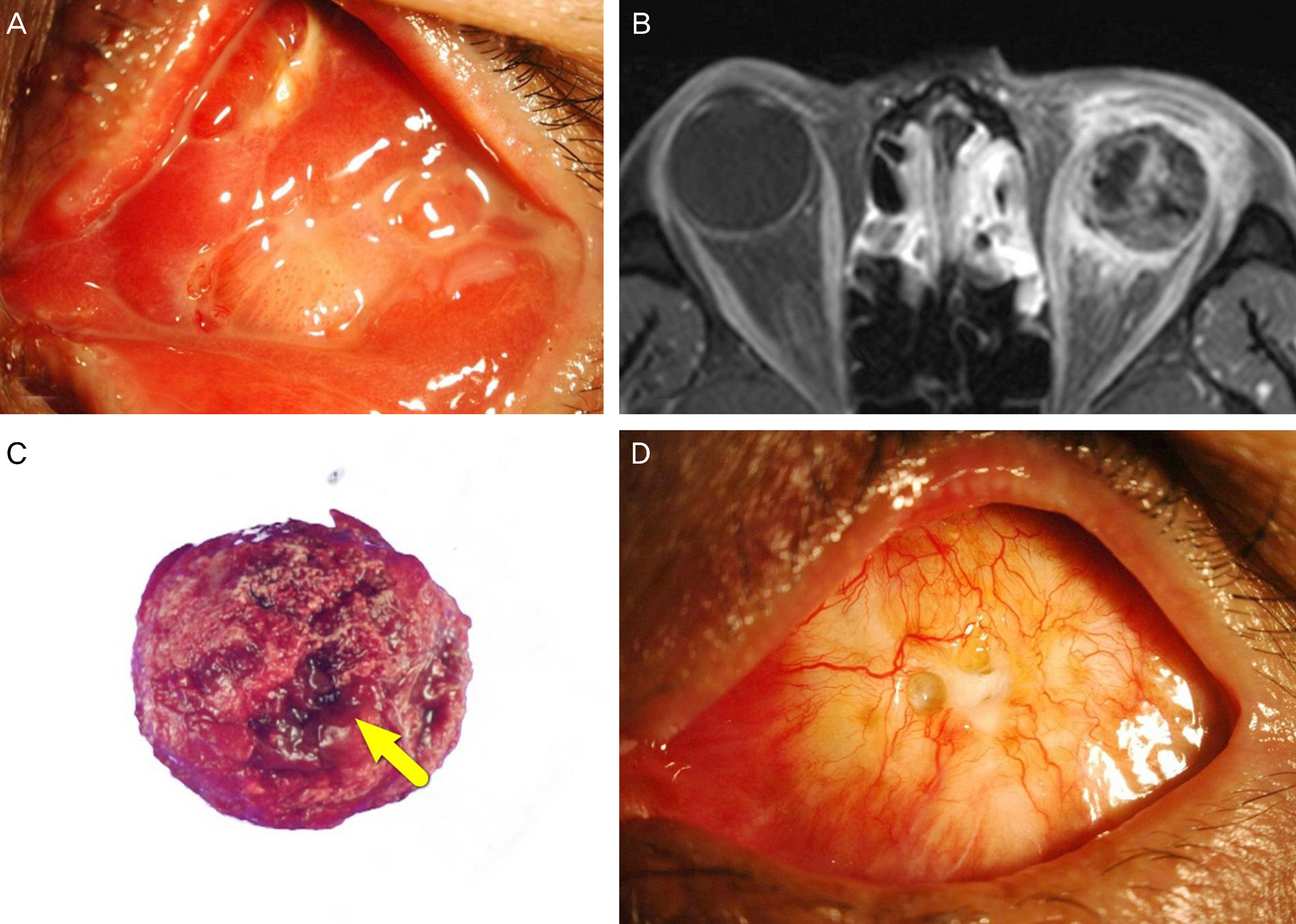

A 44-year-old male and a 55-year-old male who underwent evisceration and implantation of a hydroxyapatite implant in the left eye 17 and 15 years prior, respectively, presented with a conjunctival sac granuloma with discharge and bleeding of 1 year duration. Both patients had a history of motility peg implantation. A large-area of the hydroxyapatite implant was exposed after removal of the granuloma. The previous orbital implant was removed, and the exposed area was covered with a dermis fat graft in both patients. On histopathological examination, Actinomyces infection in the orbital implant was observed in both patients.

CONCLUSIONS

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of actinomycosis of hydroxyapatite orbital implant in Korea. In a patient with a porous orbital implant, the possibility of Actinomyces infection of the orbital implant should be considered after a long-duration and large-area exposure of the implant.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Smego RA Jr. Actinomycosis of the central nervous system. Clin Infect Dis. 1987; 9:855–65.

Article2. Hussain I, Bonshek RE, Loudon K, et al. Canalicular infection caused by Actinomyces. Eye. 1993; 7:542–4.

Article3. Weese WC, Smith IM. A study of 57 cases of actinomycosis over a 36-year period. A diagnostic “failure” with good prognosis after treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1975; 135:1562–8.

Article4. Sudhakar SS, Ross JJ. Short-term treatment of actinomycosis: two cases and a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38:444–7.

Article5. Bennhoff DF. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic consid-erations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984; 94:1198–217.6. Schaal KP, Lee HJ. Actinomycete infections in humans - a review. Gene. 1992; 115:201–11.

Article7. Karcioglu ZA. Actinomyces infection in porous polyethylene orbi-tal implant. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997; 235:448–51.

Article8. Brown JR. Human actinomycosis. A study of 181 subjects. Hum Pathol. 1973; 4:319–30.9. Brook I. Actinomycosis: diagnosis and management. South Med J. 2008; 101:1019–23.

Article10. Moghimi M, Salentijn E, Debets-Ossenkop Y, et al. Treatment of Cervicofacial Actinomycosis: A report of 19 cases and review of literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013; 18:e627–32.

Article11. Park JW, Choi WC, Sires BS, La TY. Orbital implant infection after drilling procedure. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2007; 48:1449–58.

Article12. Goldberg RA, Holds JB, Ebrahimpour J. Exposed hydroxyapatite orbital implants: Report of 6 Cases. Ophthalmology. 1992; 99:831–6.13. You SJ, Yang HW, Lee HC, Kim SJ. 5 Case of infected Hydroxya-patite Orbital Implant. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2002; 43:1553–7.14. Yang YH, Ahn M. Outcomes of autogenous dermis fat grafting with different donor sites in exposed porous orbital implants. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013; 54:545–51.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Study of the Complications in Titanium Motility Pegged Hydroxyapatite Orbital Implant

- Clinical Experience of the Secondary Hydroxyapatite Orbital Implant

- Infected Hydorx yapatite Implant by Pseudomonas Aeroginosa

- 5 cases of Infected Hydroxyapatite Orbital Implant

- Comparison of Clinical Results between Hydroxyapatite and Medpor(R) Orbital Implant