J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2014 May;55(5):702-710. 10.3341/jkos.2014.55.5.702.

The Change of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness after Posterior Chamber Phakic Intraocular Lens Implantation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea. exo70@naver.com

- KMID: 2218091

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2014.55.5.702

Abstract

- PURPOSE

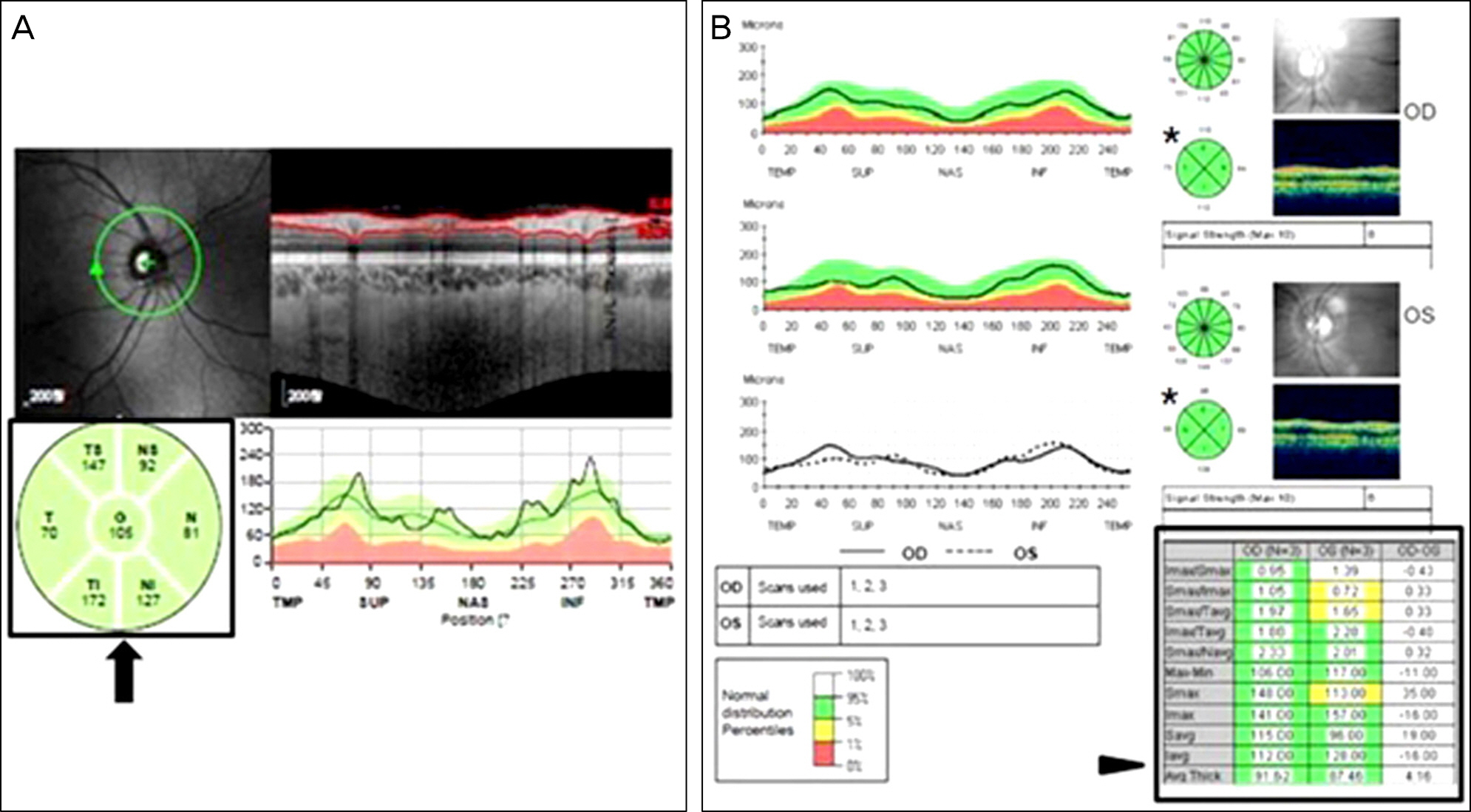

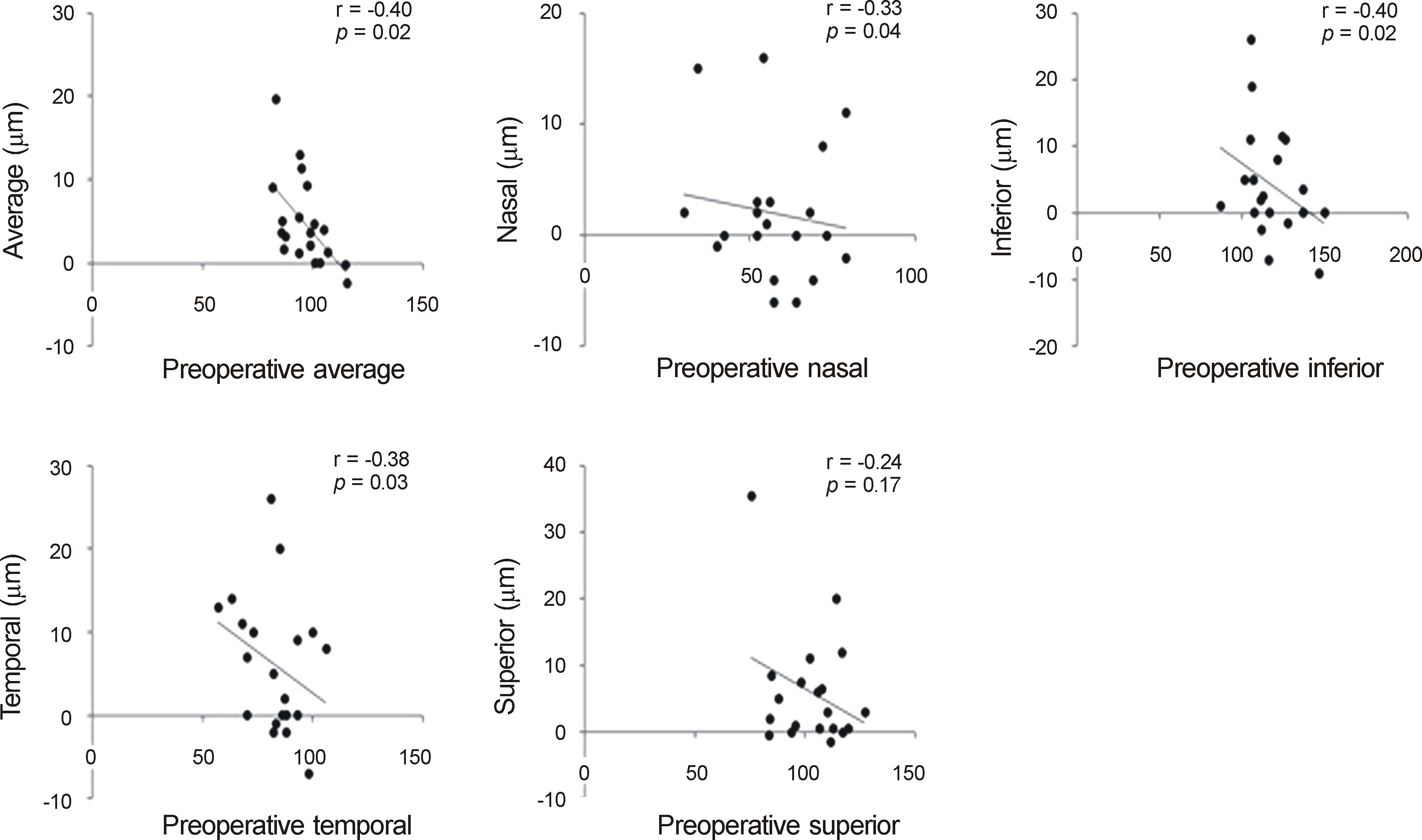

In the present study we evaluated the changes of measured retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness using optical coherence tomography (OCT) after phakic intraocular lens (implantable collamer lens, ICL) implantation and analyzed the factors correlated with the changes of measured RNFL thickness.

METHODS

Forty eyes of 40 patients (Group A: 20 patients using spectral domain OCT and Group B: 20 patients using time domain OCT) who underwent ICL implantation were included in this study. RNFL thickness was measured 1 week before surgery and 1 month postoperatively using OCT. The changes of measured RNFL thickness and the correlation between patients' data were analyzed.

RESULTS

The postoperative measured RNFL thickness of the average, inferior, temporal, and superior quadrants were increased compared to preoperative measured RNFL thickness in Group A. Group B had similar results in the average, inferior, and superior quadrants (p < 0.05). However, the postoperative changes of RNFL measurements were not correlated with the preoperative spherical equivalent, the degree of spherical equivalent change and diopters of implanted lens (p > 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

The measured RNFL thickness after ICL implantation may increase compared to the preoperative value. Caution should be taken when interpreting the RNFL thickness values measured by OCT in patients with myopia who undergo ICL implantation.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

The Effect of Refractive Power on Retinal Volume Measurement Using Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography

Myungshin Lee, Kiyeob Nam, Seunguk Lee, Sangjoon Lee

J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2018;59(2):153-158. doi: 10.3341/jkos.2018.59.2.153.

Reference

-

References

1. Amoils SP, Deist MB, Gous P, Amoils PM. Iatrogenic keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis for less than −4.0 to −7.0 diopters of myopia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000; 26:967–77.

Article2. Jimenez-Alfaro I, Gomez-Telleria G, Bueno JL, Puy P. Contrast sensitivity after posterior chamber phakic intraocular lens implantation for high myopia. J Refract Surg. 2001; 17:641–5.

Article3. Huang D, Schallhorn SC, Sugar A, et al. Phakic intraocular lens implantation for the correction of myopia: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:2244–58.4. Lee SY, Cheon HJ, Baek TM, Lee KH. Implantable contact lens to correct high myopia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2000; 41:1515–22.5. Strampelli B. Tolerance of acrylic lenses in the anterior chamber in aphakia and refraction disorders. Ann Ottalmol Clin Ocul. 1954; 80:75–82.6. Fyodorov SN, Zuyev VK, Aznabayev BM. Intraocular correction of high myopia with negative posterior chamber lens. Ophthalmosurgery. 1991; 3:57–8.7. El Danasoury MA, El Maghraby A, Gamali TO. Comparison of iris-fixed Artisan lens implantation with excimer laser in situ keratomileusis in correcting myopia between −9.00 and −19.50 diopters: a randomized study. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109:955–64.8. Sanders DR. Matched population comparison of the Visian implantable collamer lens and standard LASIK for myopia of −3.00 to −7.88 diopters. J Refract Surg. 2007; 23:537–53.

Article9. Schallhorn S, Tanzer D, Sanders DR, Sanders ML. Randomized prospective comparison of Visian toric implantable collamer lens and conventional photorefractive keratectomy for moderate to high myopic astigmatism. J Refract Surg. 2007; 23:853–67.

Article10. Alio JL, de la Hoz F, Perez-Santonja JJ, et al. Phakic anterior chamber lenses for the correction of myopia: a 7-year cumulative analysis of complications in 263 cases. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:458–66.11. Budo C, Hessloehl JC, Izak M, et al. Multicenter study of the Artisan phakic intraocular lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000; 26:1163–71.

Article12. Quigley HA, Katz J, Derick RJ, et al. An evaluation of optic disc and nerve fiber layer examinations in monitoring progression of early glaucoma damage. Ophthalmology. 1992; 99:19–28.

Article13. Leung CK, Chan WM, Yung WH, et al. Comparison of macular and peripapillary measurements for the detection of glaucoma: an optical coherence tomography study. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112:391–400.14. Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter, HRT II confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, and stratus OCT optical coherence tomography for the detection of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122:827–37.15. Hood DC, Raza AS, Kay KY, et al. A comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness obtained with frequency and time domain optical coherence tomography (OCT). Opt Express. 2009; 17:3997–4003.

Article16. Inoue R, Hangai M, Kotera Y, et al. Three-dimensional high-speed optical coherence tomography imaging of lamina cribrosa in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:214–22.

Article17. Leung CK, Cheung CY, Weinreb RN, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer imaging with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: a variability and diagnostic performance study. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:1257–63.18. Sharma N, Sony P, Gupta A, Vajpayee RB. Effect of laser in situ keratomileusis and laser-assisted subepithelial keratectomy on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006; 32:446–50.

Article19. Chen CS, Natividad MG, Earnest A, et al. Comparison of the influence of cataract and pupil size on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements with time-domain and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011; 39:215–21.20. Budenz DL, Anderson DR, Varma R, et al. Determinants of normal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by Stratus OCT. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:1046–52.

Article21. Savini G, Barboni P, Parisi V, Carbonelli M. The influence of axial length on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and optic-disc size measurements by spectral-domain OCT. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012; 96:57–61.22. Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CK, et al. Epidemiologic study of the prevalence and severity of myopia among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 2000. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001; 100:684–91.23. Kang SH, Kim PS, Choi DG. Prevalence of myopia in 19-year-old Korean males: The relationship between the prevalence and education or urbanization. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2004; 45:2082–7.24. Mohammad Salih PA. Evaluation of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in myopic eyes by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2012; 21:41–4.

Article25. Kang SH, Hong SW, Im SK, et al. Effect of myopia on the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer measured by Cirrus HD optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51:4075–83.

Article26. Han SY, Lee KH. Long term effect of ICL implantation to treat high myopia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2007; 48:465–72.27. Chun YS, Lee JH, Lee JM, et al. Outcomes after implantable contact lens for moderate to high myopia. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2004; 45:480–9.28. Gurses-Ozden R, Liebmann JM, Schufïner D, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness remains unchanged following laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001; 132:512–6.29. Knight OJ, Chang RT, Feuer WJ, Budenz DL. Comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer measurements using time domain and spectral domain optical coherent tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009; 116:1271–7.

Article30. Budenz DL, Fredette MJ, Feuer WJ, Anderson DR. Reproducibility of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber thickness measurements with Stratus OCT in glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:661–6.

Article31. Schuman JS, Pedut-Kloizman T, Hertzmark E, et al. Reproducibility of nerve fiber layer thickness measurements using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:1889–98.

Article32. Knighton RW, Qian C. An optical model of the human retinal nerve fiber layer: implications of directional reflectance for variability of clinical measurements. J Glaucoma. 2000; 9:56–62.

Article33. Wang XY, Huynh SC, Burlutsky G, et al. Reproducibility of and effect of magnification on optical coherence tomography measurements in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 143:484–8.

Article34. Salchow DJ, Hwang AM, Li FY, et al. Effect of contact lens power on optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52:1650–4.

Article35. Aristeidou AP, Labiris G, Paschalis EI, et al. Evaluation ofthe retinal nerve fiber layer measurements, after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis, using scanning laser polarimetry (GDx VCC). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010; 248:731–6.36. Littmann H. Determination of the real size of an obj ect on the fundus of the living eye. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1982; 180:286–9.37. Bennett AG, Rudnicka AR, Edgar DF. Improvements on Littmann's method of determining the size of retinal features by fundus photography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994; 232:361–7.

Article38. Bayraktar S, Bayraktar Z, Yilmaz OF. Influence of scan radius correction for ocular magnification and relationship between scan radius with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography. J Glaucoma. 2001; 10:163–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Posterior Chamber Intraocular Lens Implantation in High Myopia

- Reproducibility of Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness Evaluation by Nerve Fiber Analyzer

- Clinical Results of Femtosecond Laser-assisted Cataract Surgery in Eyes with Posterior Chamber Phakic Intraocular Lens

- Anterior Chamber Phakic Intraocular lens in Patients with high Myopia

- Posterior Capsular Rupture in Planned ECCE for Posterior Chamber Intraocular Lens Implantation