J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2013 May;54(5):766-770. 10.3341/jkos.2013.54.5.766.

The Influence of Suppression on Axial Length Progression in Intermittent Exotropia

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. ansaneye@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2217043

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2013.54.5.766

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To evaluate the influence of suppression by intermittent exotropia on axial length progression.

METHODS

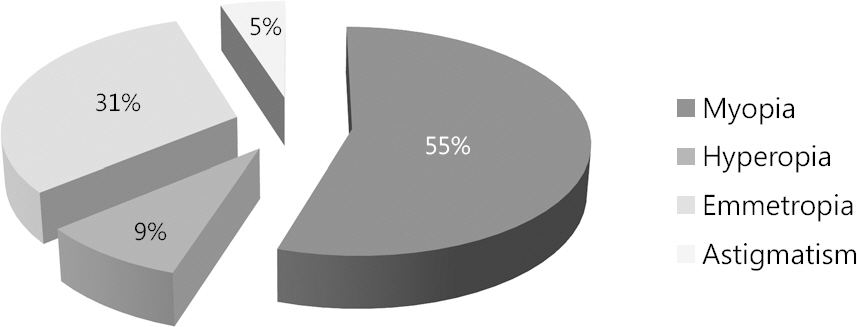

The medical records of patients with intermittent exotropia who had undergone surgery at the Korea University Medical Center from 2003 to 2010 were reviewed. The age upon visit, age at operation, visual acuity, refractive error, type of strabismus, angle of strabismic deviation, suppression test (Vectographic projector test, Reneau, France), and axial length test were analyzed. Subjects with amblyopia or anisometropia were excluded.

RESULTS

A total of 75 patients with intermittent exotropia who had definite suppression in 1 eye were identified. The mean age at visit was 6.87 +/- 2.73 years and mean angle of exodeviation was 25.65 +/- 6.68 / 26.17 +/- 6.59 (prism diopters, distant / near). There was no statistical difference in exotropia patients' interocular axial length value who showed suppression in 1 eye (p = 0.992 in the right-eye suppression group, and p = 0.528 in the left-eye suppression group).

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, there was no statistical difference in interocular axial length value of intermittent exotropia patients with suppression in one eye (p > 0.05).

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Johnson CA, Post RB, Chalupa LM, Lee TJ. Monocular depriva-tion in humans: a study of identical twins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982; 23:135–8.2. Gottlieb MD, Fugate-Wentzek LA, Wallman J. Different visual deprivations produce different ametropias and different eye shapes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987; 28:1225–35.3. Smith ME, Becker B, Podos S. Light-induced angle-closure glau-coma in the domestic fowl. Invest Ophthalmol. 1969; 8:213–21.4. Zarbin MA, Wamsley JK, Palacios JM, et al. Autoradiographic lo-calization of high affinity GABA, benzodiazepine, dopaminergic, adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the rat, monkey and human retina. Brain Res. 1986; 374:75–92.

Article5. Dubochovich ML, Weiner N. Pharmacological difference between the D-2 autoreceptor and D-1 dopamine receptor in the rabbit retina. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985; 223:747–54.6. Iuvone PM, Tigges M, Stone RA, et al. Effect of apomorphine, a dopamine receptor agonist, on ocular refraction and axial elonga-tion in a primate model of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991; 32:1674–7.7. Wallman J, Turkel J, Trachtman J. Extreme myopia produced by modest changes in early visual experience. Science. 1978; 201:1249–51.8. Sherman SM, Norton TT, Casagrande VA. Myopia in the lid-su-tured tree shrew (Tupaia glis). Brain Res. 1977; 124:154–7.

Article9. Wiesel TN, Raviola E. Myopia and eye enlargement after neonatal lid fusion in monkeys. Nature. 1977; 266:66–8.

Article10. Troilo D, Gottlied MD, Wallman J. Visual deprivation causes my-opia in chicks with optic nerve section. Curr Eye Res. 1987; 6:993–9.

Article11. Caltrider N, Jampolsky A. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983; 90:1160–5.

Article12. Walsh LA, Laroche GR, Tremblay F. The use of binocular visual acuity in the assessment of intermittent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2000; 4:154–7.

Article13. Joosse MV, Esme DL, Schimsheimer RJ, et al. Visual evoked po-tentials during suppression in exotropic and esotropic strabismics: strabismic suppression objectified. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005; 243:142–50.

Article14. von Noorden GK. Sensory signs, symptoms, and binocular adapta-tions in strabismus. In: Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby;2002. p. 215–21.15. Chia A, Roy L, Seenyen L. Comitant horizontal strabismus: an Asian perspective. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007; 91:1337–40.

Article16. Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Sjöstrand J. Refraction changes in children developing convergent or divergent strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992; 76:723–7.

Article17. Ingram RM, Gill LE, Lambert TW. Emmetropisation in normal and strabismic children and the associated changes of anisometropia. Strabismus. 2003; 11:71–84.

Article18. Kushner BJ. Does overcorrecting minus lens therapy for inter-mittent exotropia cause myopia? Arch Ophthalmol. 1999; 117:638–42.

Article19. Chua WH, Balakrishnan V, Chan YH, et al. Atropine for the treat-ment of childhood myopia. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113:2285–91.

Article20. Sengpiel F, Jirmann KU, Vorobyov V, Eysel UT. Strabismic sup-pression is mediated by inhibitory interactions in the primary visual cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2006; 16:1750–8.

Article21. Lawwill T, Biersdorf WR. Binocular rivalry and visual evoked responses. Invest Ophthalmol. 1968; 7:378–85.22. Lawwill T, Meur G, Howard CW. Lateral inhibition in the central visual field of an amblyopic subject. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973; 76:225–8.

Article23. Funata M, Tokoro T. Scleral change in experimentally myopic monkeys. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990; 228:174–9.

Article24. Christensen AM, Wallman J. Evidence that increased scleral growth underlies visual deprivation myopia in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991; 32:2143–50.25. Stone RA, Laties AM, Raviola E, Wiesel TN. Increase in retinal vasoactive intestinal polypeptide after eyelid fusion in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988; 85:257–60.

Article26. Saw SM, Chua WH, Hong CY, et al. Nearwork in early-onset myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002; 43:332–9.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Distance Suppression as a Predictive Factor in Progression of Intermittent Exotropia

- The Influence of Axial Length on the Response to Strabismus Surgery

- The Photophobia Incidence, Stereopsis and Suppression in Intermittent Exotropia

- Surgieal Result of Intermittent Exotropia: Comparison of Sensory Anomaly

- Clinical Findings of Constant Exotropia Developed from Intermittent Exotropia