J Korean Ophthalmol Soc.

2015 Sep;56(9):1377-1385. 10.3341/jkos.2015.56.9.1377.

Association between Decreased Visual Acuity and Self-Report Depressive Disorder or Depressive Mood: KNHANES IV

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea. eunjee95@nhimc.or.kr

- KMID: 2214553

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3341/jkos.2015.56.9.1377

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To assess the association between decreased visual acuity (VA) and diagnosis of depressive disorder by a physician or experience of depressive mood using self-report questionnaires.

METHODS

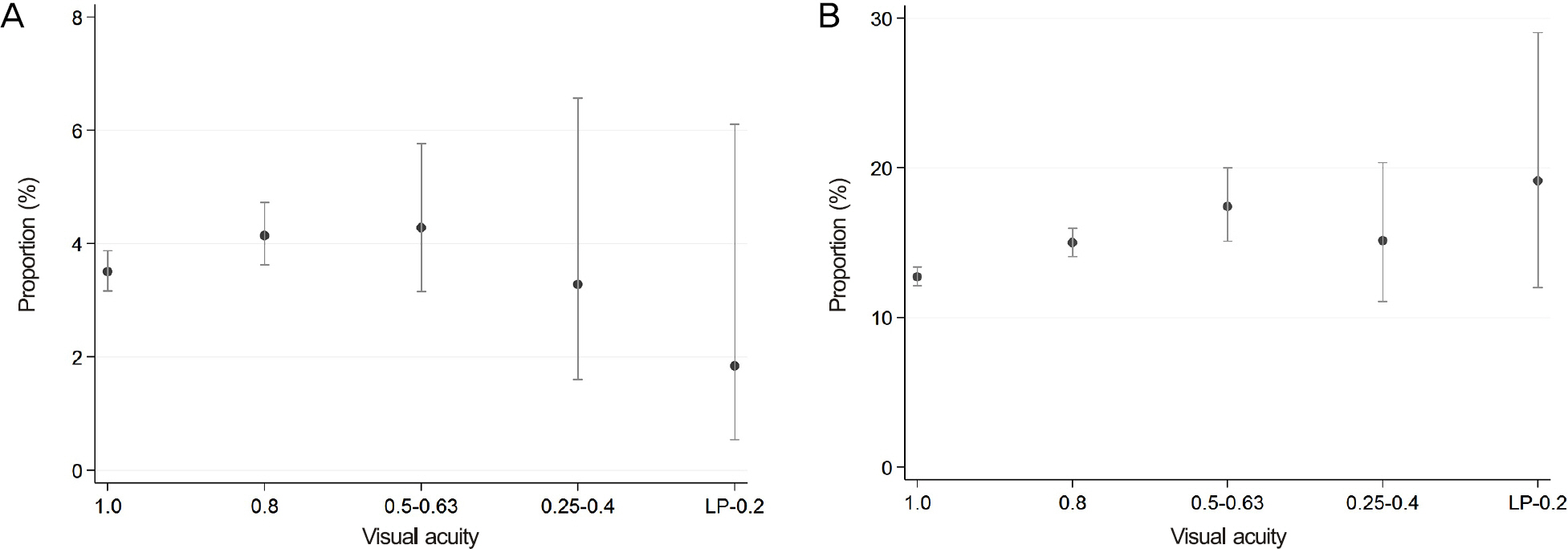

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using nationally representative data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES, 2008-2012). A total of 28,919 adults who had sociodemographic and health behavioral risk factors available were included. An association between decreased VA and depression was identified using multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for possible confounders. Depression was defined as a depressive disorder with a diagnosis by a physician or depressive mood lasting more than 2 weeks using self-report questionnaires.

RESULTS

The prevalence of depressive disorder and depressive mood in Koreans was 1,160 (4.0%) and 4,063 (14.1%), respectively. In univariable logistic regression, there was significant association between VA and depressive disorder or depressive mood. However, in multivariable logistic regression analysis, this study found no statistically significant association between VA status and the prevalence of depressive disorder or depressive mood in Koreans.

CONCLUSIONS

No association between decreased VA and a depressive disorder/depressive mood in Korean adults after adjusting for possible confounders was found. Therefore, further longitudinal cohort studies examining the causal relationship between decreased VA and depression in Korean adults are necessary.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. World Health Organization Global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness: action plan 2006-2011. Geneva: World Health Organization,. 2007; 1–89.2. World Health Organization Global data on visual impairments 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization,. 2012; 1–14.3. Rim TH, Nam JS, Choi M. . Prevalence and risk factors of vis-ual impairment and blindness in Korea: the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2008-2010. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014; 92:e317–25.

Article4. Horowitz A, Reinhardt JP, Kennedy GJ. Major and subthreshold depression among older adults seeking vision rehabilitation services. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005; 13:180–7.

Article5. McDonnall MC. Risk factors for depression among older adults with dual sensory loss. Aging Ment Health. 2009; 13:569–76.

Article6. Rees G, Tee HW, Marella M. . Vision-specific distress and de-pressive symptoms in people with vision impairment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51:2891–6.

Article7. Casten R, Rovner B. Depression in age-related macular degeneration. J Vis Impair Blind. 2008; 102:591–9.

Article8. Augustin A, Sahel JA, Bandello F. . Anxiety and depression prevalence rates in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48:1498–503.

Article9. Brody BL, Gamst AC, Williams RA. . Depression, visual acui-ty, comorbidity, and disability associated with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:1893–900.

Article10. Rovner BW, Casten RJ. Activity loss and depression in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002; 10:305–10.

Article11. Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Tasman WS. Effect of depression on vision function in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120:1041–4.

Article12. Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT. . Low vision depression prevention trial in age-related macular degeneration: a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2014; 121:2204–11.13. Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Massof RW. . Psychological and cog-nitive determinants of vision function in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129:885–90.

Article14. Leung JC, Kwok TC, Chan DC. . Visual functioning and qual-ity of life among the older people in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012; 27:807–15.

Article15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical man-ual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington: American Psychiatric Association;1994. p. 317–91.16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health ques-tionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003; 41:1284–92.17. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997; 12:439–45.

Article18. Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, Rapaport MH. Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depres-sion in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153:1411–7.19. Park JH, Kim KW. Subsyndromal depression. Korean J Biol Psychiatry. 2011; 18:210–6.20. Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS. . Diagnosis and treat-ment of depression in late life. Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997; 278:1186–90.

Article21. Rodu B, Cole P. Smoking prevalence: a comparison of two American surveys. Public Health. 2009; 123:598–601.

Article22. Casten RJ, Rovner BW. Update on depression and age-related mac-ular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013; 24:239–43.

Article23. Rovner BW, Ganguli M. Depression and disability associated with impaired vision: the MoVies Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998; 46:617–9.

Article24. Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RP. Depression and anxiety in visually impaired older people. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114:283–8.

Article25. Jones GC, Rovner BW, Crews JE, Danielson ML. Effects of de-pressive symptoms on health behavior practices among older adults with vision loss. Rehabil Psychol. 2009; 54:164–72.

Article26. Bandello F, Lafuma A, Berdeaux G. Public health impact of neo-vascular age-related macular degeneration treatments extrapolated from visual acuity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48:96–103.

Article27. Zhang X, Bullard KM, Cotch MF. . Association between de-pression and functional vision loss in persons 20 years of age or older in the United States, NHANES 2005-2008. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131:573–81.

Article28. Goldstein JE, Massof RW, Deremeik JT. . Baseline traits of low vision patients served by private outpatient clinical centers in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130:1028–37.

Article29. Chang SM, Hahm BJ, Lee JY. . Cross-national difference in the prevalence of depression caused by the diagnostic threshold. J Affect Disord. 2008; 106:159–67.

Article30. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005; 1:293–319.

Article31. Sheets ES, Craighead WE. Comparing chronic interpersonal and noninterpersonal stress domains as predictors of depression re-currence in emerging adults. Behav Res Ther. 2014; 63:36–42.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Relationship between Clothing Behavior & Depressive Mood

- Temporal Lobe Volume Measurement in Mood Disorder Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- A Case of Bright Light Therapy in a Treatment Resistant Patient with Major Depressive Disorder

- The Attention of Primary Physician on Depression of the Elderly Patients

- Dysfunctional Breathing in Anxiety and Depressive Disorder