J Korean Hip Soc.

2011 Jun;23(2):95-102. 10.5371/jkhs.2011.23.2.95.

Anterior Approaches in Hip Surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Institute for Skeletal Aging, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea. totalhip@hallym.ac.kr

- KMID: 2190719

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5371/jkhs.2011.23.2.95

Abstract

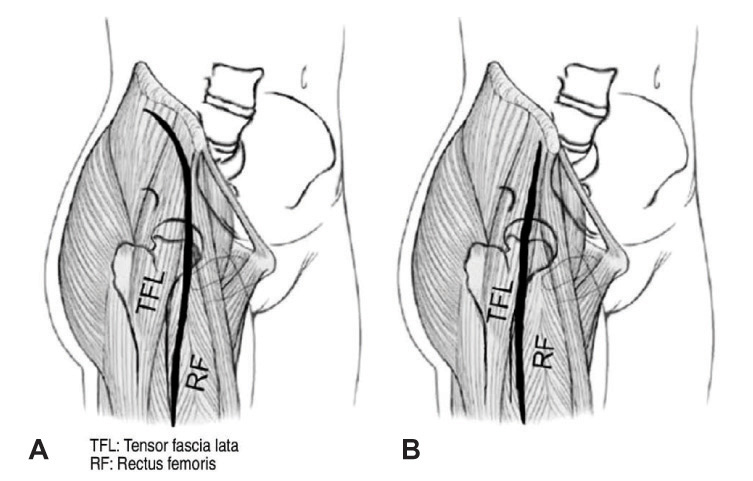

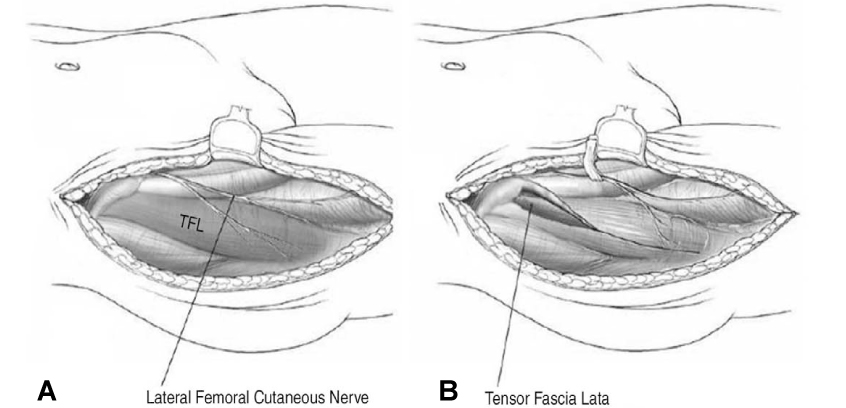

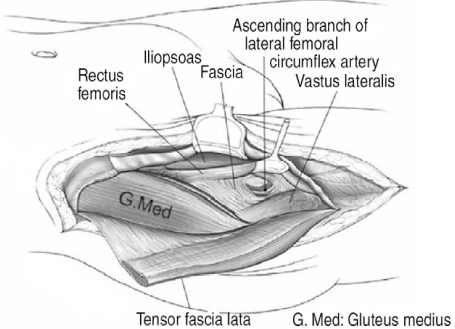

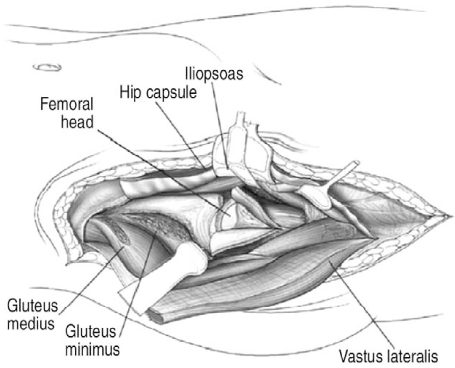

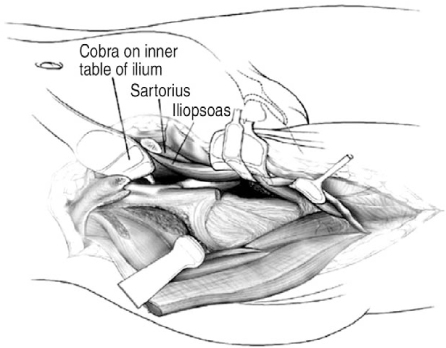

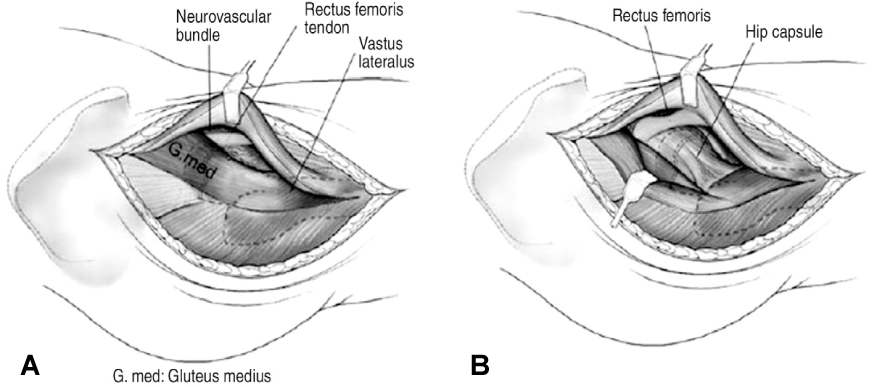

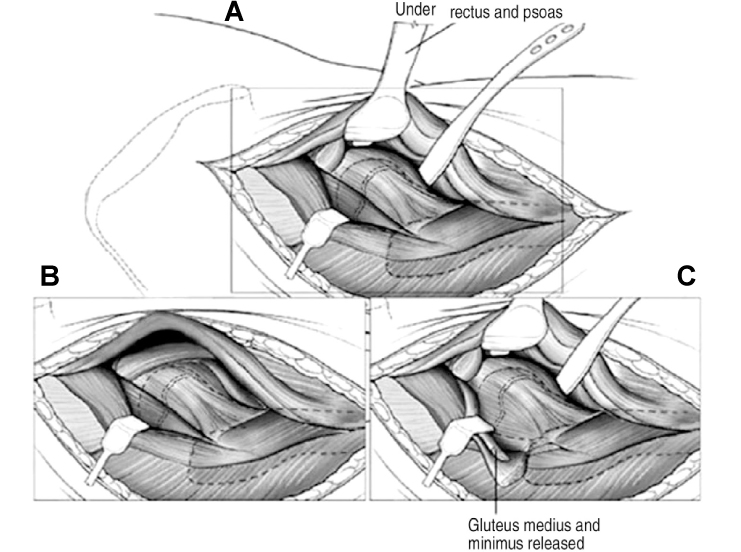

- The Smith-Petersen anterior approach and the Watson-Jones anterolateral approach are the two most renowned anterior approaches for hip surgery. The anterior approach offers several advantages, including a reduced dislocation risk as compared with that associated with the posterior approach. The post-operative dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty is known to be 2~3 times lower than that of the posterior approach. However, a more extensive skin incision and poor anatomical visualization are some of the disadvantages of the anterior approach. Nevertheless, since this approach preserves the circulation to the femoral head, the ability to perform the anterior approach is imperative for hip surgeons.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Moon DH. Anterior approach of the hip. J Korean Hip Soc. 2007. 19:319–323.2. Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982. 64:17–19.

Article3. Smith-Petersen MN. Approach to and exposure of the hip joint for mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1949. 31A:40–46.

Article4. Callaghan JJ, Rosenberg AG, Rubash HE. The adult hip. 2007. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;685–694.5. Hoppenfeld S, deBoer P. Surgical exposure in orthopaedics. 2003. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;365–453.6. Barton C, Kim PR. Complications of the direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2009. 40:371–375.

Article7. van Oldenrijk J, Hoogland PV, Tuijthof GJ, Corveleijn R, Noordenbos TW, Schafroth MU. Soft tissue damage after minimally invasive THA. Acta Orthop. 2010. 81:696–702.

Article8. Ivins GK. Meralgia paresthetica, the elusive diagnosis: clinical experience with 14 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2000. 232:281–286.9. Hueter C. Hueter C, editor. Fünfte abtheilung: die verletzung und krankheiten des hüftgelenkes, neunundzwanzigstes capitel. 1883. Leipzig: FCW Vogel;129–200.10. Ince A, Kemper M, Waschke J, Hendrich C. Minimally invasive anterolateral approach to the hip: risk to the superior gluteal nerve. Acta Orthop. 2007. 78:86–89.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Patient-Reported Outcome Measures of Staged Direct Anterior Approach and Direct Lateral Approach for Total Hip Arthroplasty Performed on the Same Patient

- Bernese Periacetabular Osteotomy Using Dual Approaches for Hip Dysplasias

- Patient Accompanied with Simultaneous Anterior Dislocation of Hip and Anterior Dislocation of Knee : A Case Report

- Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Hip Surgery Patients

- Treatment of Complex Tibial Plateau Fractures: A Modified Patient Positioning for the Combined Anterior and Posterior Approaches