J Korean Med Assoc.

2008 Apr;51(4):306-316. 10.5124/jkma.2008.51.4.306.

Treatment of Medically Intractable End-Stage Heart Failure

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Korea. jin-ho.choi@samsung.com

- 2Department of Cardiology, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Korea. esjeon@skku.edu

- KMID: 2185739

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2008.51.4.306

Abstract

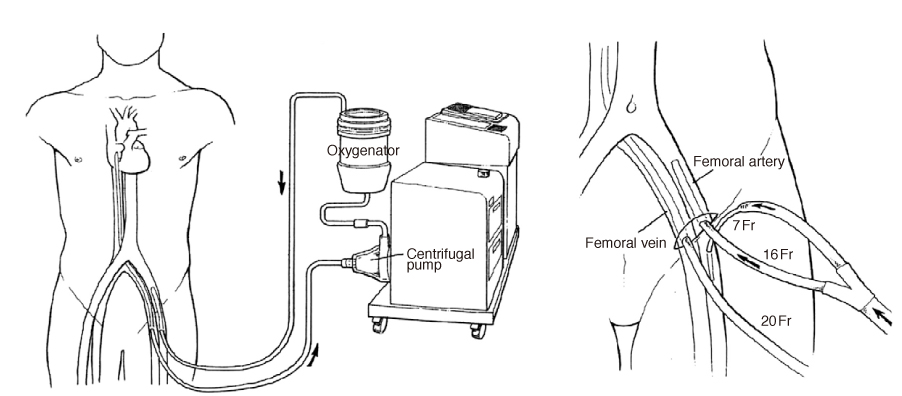

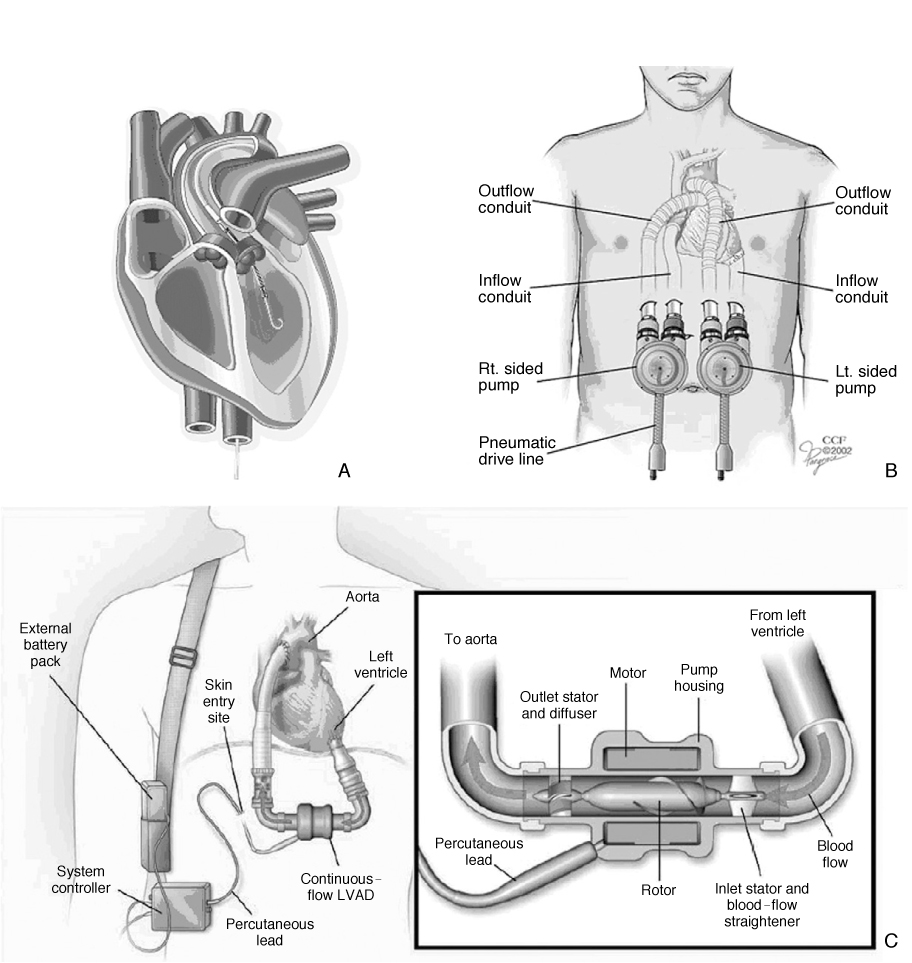

- Heart failure is the final pathway for myriad diseases that affect the heart. Patients with refractory symptoms of heart failure despite ultimate medical therapy have very poor prognosis. In these patients, replacement of failing heart with permanent organ transplantation or ventricular assist device, which is temporarily or permanently implanted, is often life-saving and can improve long term prognosis. Cardiac transplantation is the established standard for the treatment of end-stage cardiac disease refractory to medical therapy. The clinical success of transplantation has been streadily improving with the refinement of recipient selection, better donor management, and better immunosuppressive agents. Recent substantial evolution of mechanical circulatory assist devices improved dramatically the outcome of not only patients in decompensated heart failure but also a large proportion of acute heart failure patients in cardiogenic shock. With this evolution, implantable sophisticated devices are being used as destination therapy as a substitute for transplantation and are expected to diminish the intrinsic shortage of donor compared to the epidemic of heart failure.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Decline in deaths from heart disease and stroke-United States, 1900~1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999. 48:649–656.2. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980~2000. N Engl J Med. 2007. 356:2388–2398.

Article3. Changes in mortality from heart failure-United States, 1980~1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998. 47:633–637.4. Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, Vasan RS. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:1397–1402.

Article5. Goldberg RJ, Ciampa J, Lessard D, Meyer TE, Spencer FA. Long-term survival after heart failure: a contemporary population-based perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2007. 167:490–496.6. Lee MM, Oh BH, Park HS, Han SW, Ryu KH. Multicenter Analysis of Clinical Characteristics of the Patients with Congestive Heart Failure in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2003. 33:533–541.

Article7. Swedberg K, Cleland J, Nieminen MS, Pierard L, Remme WJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005. 26:1115–1140.8. Lindenfield J, Miller GG, Shaker SF, Zolty R, Kobashigawa J. Drug therapy in the Heart transplant recipient Part I to part III. Circulation. 2005. 111:113–117. 2004; 110: 3734-3740, 2004; 110: 3858-3865.9. Eisen HJ, Tuzcu EM, Dorent R, Bernhart P. for the RAD study group. Everolimus for the prevention of allograft rejection and vasculopathy in cardiac transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2003. 349:847–858.

Article10. Beniaminovita A, Itescu S, Letz K, Mancini DM. Prevention of rejection in cardiac transplantation by blockade of the interleukin-2 receptor with a monoclonal antibody. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:613–619.

Article11. Balfore IC, Fiore A, Graff RJ, Knutsen AP. Use of rituximab to decrease panel-reactive antibodies. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005. 24:628–630.

Article12. Taylor DO, Edwards LB, Boucek MM, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-fourth official adult heart transplant report-2007. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007. 26:769–781.

Article13. Goldstein DJ, Oz MC, Rose EA. Implantable left ventricular assist devices. N Engl J Med. 1998. 339:1522–1533.

Article14. Stevenson LW, Kormos RL, Bourge RC, Gelijns A, Griffith BP, Wichman A. Mechanical cardiac support 2000: current applications and future trial design. June 15~16, 2000 Bethesda, Maryland. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001. 37:340–370.

Article15. Maybaum S, Mancini D, Xydas S, Torre-Amione G. Cardiac improvement during mechanical circulatory support: a prospective multicenter study of the LVAD Working Group. Circulation. 2007. 115:2497–2505.

Article16. Muller J, Wallukat G, Weng YG, Hetzer R. Weaning from mechanical cardiac support in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997. 96:542–549.

Article17. McCarthy RE 3rd, Boehmer JP, Hruban RH, Hutchins GM, Kasper EK, Hare JM, Baughman KL. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000. 342:690–695.

Article18. Seong IW, Choe SC, Jeon ES. Fulminant coxsackieviral myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2001. 345:379.

Article19. Cooper LT Jr, Berry GJ, Shabetai R. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis-natural history and treatment. N Engl J Med. 1997. 336:1860–1866.

Article20. Park JI, Jeon ES. Mechanical Circulatory Supports in the Treatment of Fulminant Myocarditis. Korean Circ J. 2005. 35:563–572.

Article21. Rhee I, Jeon ES. Giant Cell Myocarditis Manifested as Fulminant Myocarditis. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:159–161.

Article22. Graner M, Lommi J, Kupari M, Raisanen-Sokolowski A, Toivonen L. Multiple forms of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia as common presentation in giant-cell myocarditis. Heart. 2007. 93:119–121.

Article23. Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Oz MC, Poirier VL. Long-term mechanical left ventricular assistance for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001. 345:1435–1443.

Article24. Catanese KA, Goldstein DJ, Williams DL, Foray AT, Illick CD, Gardocki MT, Weinberg AD, Levin HR, Rose EA, Oz MC. Outpatient left ventricular assist device support: a destination rather than a bridge. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996. 62:646–652. discussion 653.

Article25. Lietz K, Long JW, Kfoury AG, Miller LW. Outcomes of left ventricular assist device implantation as destination therapy in the post-REMATCH era: implications for patient selection. Circulation. 2007. 116:497–505.

Article26. Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, John R, Farrar DJ, Frazier OH. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357:885–896.

Article27. Rhee I, Gwon HC, Choi J, Sung K, Lee YT, Kwon SU, Cho DK, Lim SH, Kim SW, Lee SH, Hong KP, Park JE. Percutaneous Cardiopulmonary Support for Emergency In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest or Cardiogenic Shock. Korean Circ J. 2006. 36:11–16.

Article28. Sung K, Lee YT, Park PW, Park KH, Jun TG, Yang JH, Ha YK. Improved survival after cardiac arrest using emergent auto-priming percutaneous cardiopulmonary support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006. 82:651–656.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Noteworthy Way to Predict Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease

- Pediatric Mechanical Circulatory Support

- Mechanical Circulatory Support to Control Medically Intractable Arrhythmias in Pediatric Patients After Cardiac Surgery

- Another, A Few Good Device for End Stage Heart Failure

- Treatment of Advanced Heart Failure: Beyond Medical Treatment