J Korean Med Assoc.

2006 Jan;49(1):63-69. 10.5124/jkma.2006.49.1.63.

Treatment of Acne

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Dermatology, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine and Hospital, Korea. snolomas@hosp.sch.ac.kr

- KMID: 2184637

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2006.49.1.63

Abstract

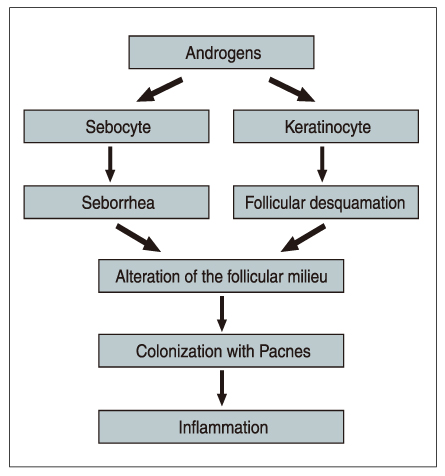

- Acne vulgaris is a self-limited disease, seen primarily in adolescents. Most cases of acne are pleomorphic, presenting various lesions consisting of comedones, pustules, and nodules. Although it has been traditionally classified as a disease of the sebaceous gland, it actually involves the pilosebaceous unit. There are four major principles in the treatment of acne: (1) correct the altered pattern of follicular keratinization; (2) decrease the sebaceous gland activity; (3) decrease the follicular bacterial population; and (4) produce anti-inflammatory effect. The natural course of acne varies greatly, and therefore, the determination of the therapeutic efficacy of medications for the treatment of acne is far from being simple.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

2. Irwin MF, Arthur ZE. Fitzpatrick's dermatology. 6th ed. New York: Mcgrawhill;672–688.3. Del Rosso JQ. Retinoic acid receptors and topical acne therapy. Cutis. 2002. 70:127–129.4. Wolf JE. An update of recent clinical trials examining adapalene and acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001. 15:Suppl 3. S23–S29.

Article5. Kakita L. Tazarotene versus tretinoin or adapalene in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 43:S51–S54.

Article6. Menter A. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tazarotene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 43:S31–S35.

Article7. Millikan LE. Adapalene: an update on newer comparative studies between the various retinoids. Int J Dermatol. 2000. 39:784–788.

Article8. Leyden JJ. Current issues in antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001. 15:Suppl 3. S51–S55.

Article9. Russell JJ. Topical therapy for acne. Am Family Physician. 2000. 61:357–366.10. Berson DS, Shalita AR. The treatment of acne: the role of combination therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995. 32:S31–S41.

Article11. Webster G. Combination azelaic acid therapy for acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 43:S47–S50.

Article12. Plewig G, Kligman AM. Acne and rosacea. 2000. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag;649–680.13. Cunliffe WJ, van de Kerkhof PC, Caputo R, Cavicchini S, Cooper A, Shaita A, et al. Roaccutane treatment guidelines: Results of an international survey. Dermatology. 1997. 194:351–357.

Article14. Wysowski DK, Swann J, Vega A. Use of isotretinoin (Accutane) in the united states: Rapid increase from 1992 through 2000. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 46:505–509.

Article15. Goodman GJ. Management of post-acne scarring. What are the options for treatment? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000. 1:3–17.16. Jacob CI, Dover JS, Kaminer MS. Acne scarring: a classification system and review of treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001. 45:109–117.

Article17. Sawcer D, Lee HR, Lowe NJ. Lasers and adjunctive treatments for facial scars: a review. J Cutan Laser Ther. 1999. 1:77–85.

Article18. Victor ER. Optical treatments for acne. Dermatologic therapy. 2005. 18:253–266.

Article