Current epidemiological situation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus clusters and implications for public health response in South Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Institute for Occupational and Environmental Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea. shine@korea.ac.kr

- 2Graduate School of Public Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Medicine, Korea University, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Research Institute for Healthcare Policy, Korean Medical Association, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2137555

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2015.58.6.487

Abstract

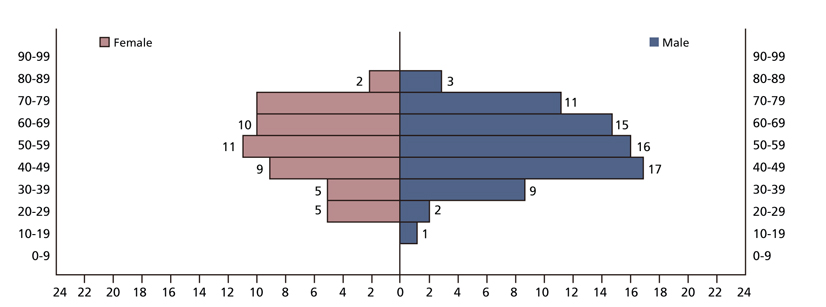

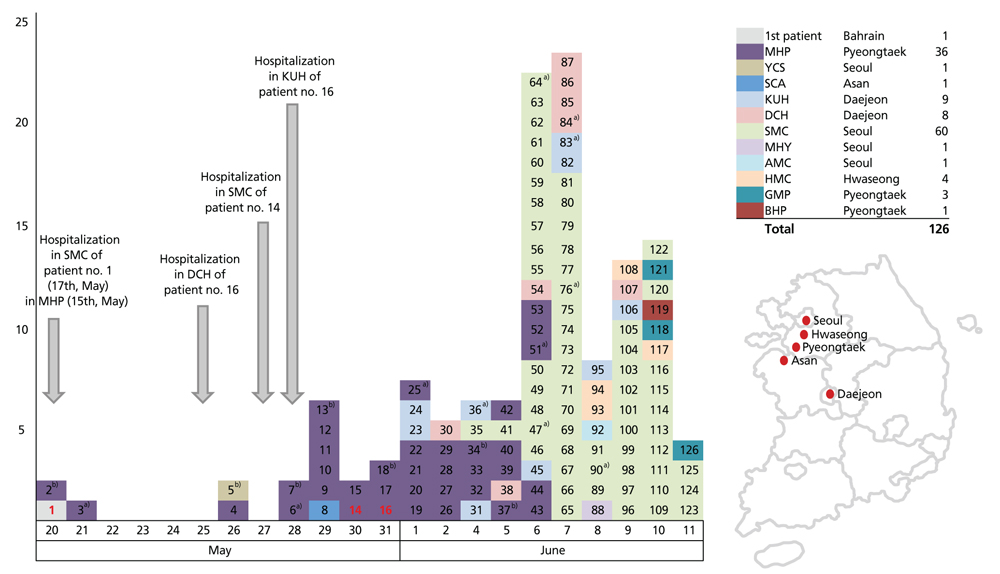

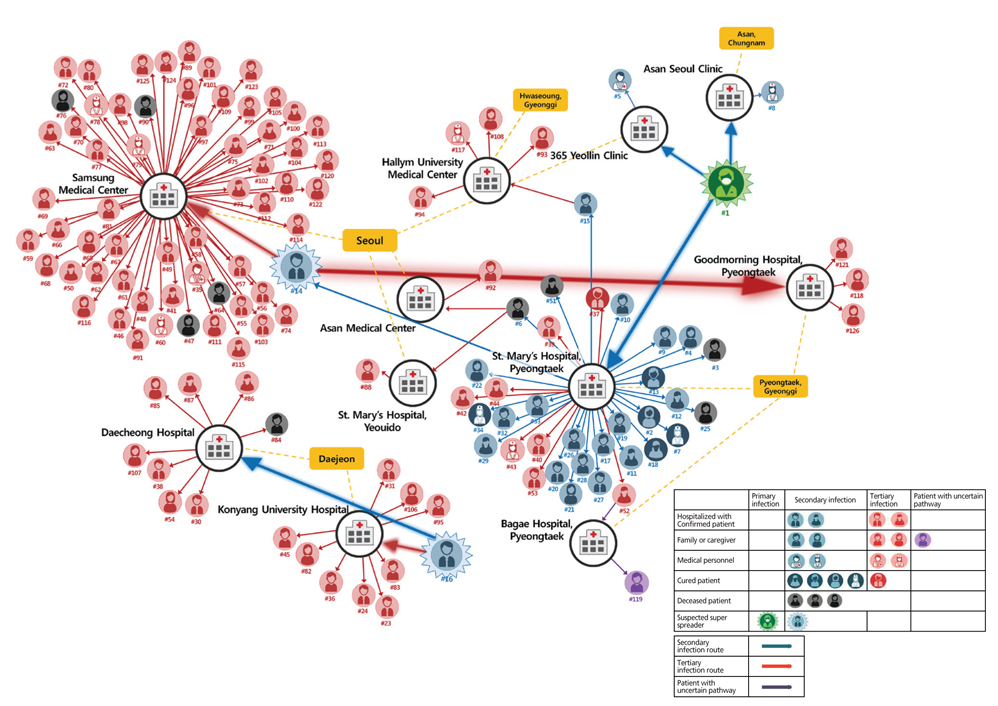

- Since May 20, 2015, when the first case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in South Korea was confirmed, the cluster case in South Korea has grown to become the largest observed case following Saudi Arabia within the span of one month. Akin to what was observed in the Middle East, confirmed cases were infected through nosocomial transmission where the cluster is largely limited to patients, healthcare workers, and visitors to patients in healthcare facilities with confirmed cases. A major difference from the outbreaks in the Arabian Peninsula has been the large number of tertiary transmission cases in South Korea, which had reached forty cases by June 12. This observation may suggest that despite the lack of genetic mutation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in South Korea, the virus may be behaving differently from that of the Middle East. The higher infectiousness of 'super-spreaders' in South Korea also suggests that this assertion should be under further investigation. Suggestions of inadequate triage in emergency rooms, particularly at Samsung Medical Center which accounts for the most nosocomial infection with 60 cases, have been made by several organizations as the basis for this rapid spread. This, however, does not account for the fact that triage was impossible to implement, since the presence of MERS-CoV in South Korea was unknown during the index patient's stay at the healthcare facilities. This paper aims to identify the key factors in the amplified spread of MERS-CoV in South Korea. The first is the initial failure to confirm diagnosis promptly and to isolate the index case after confirmation of MERS in hospital and the lack of detail in tracking potential exposures in the community of the index case before isolation. The second is the early inadequate measures the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took in categorizing close contacts. Due to inconsistencies in defining what constitutes close contact, a number of cases were neglected from quarantine and were not subjected to investigation. Finally, confirmed or potential MERS patients were admitted for treatment and observation at medical facilities without adequate disease control measures or rooms, such as ventilated single rooms or airborne precaution rooms. Due to the rigid position that MERS-CoV cannot be transmitted via airborne means, infection control measures has so far neglected evidence that smaller droplets (aerosol) containing the virus can act similar to airborne agents, which may account for the widespread and rapid transmission in a emergency room and a patient's room in hospital. Although the South Korean government expects newly confirmed cases to abate in the coming few weeks, without stringent implementation of clearly defined guidelines to control further transmissions, the cessation of the current trend may continue for an extended period. Additionally, due to the high infection rate of super-spreaders in South Korea, efforts to screen for potential super-spreaders and a thorough investigation of those confirmed to be super-spreaders should be done to quickly identify source of infection, to potentially lower the number of secondary, tertiary transmissions and prevent possible quaternary transmissions.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.)

Communicable Diseases

Coronavirus*

Cross Infection

Delivery of Health Care

Diagnosis

Disease Outbreaks

Emergency Service, Hospital

Epidemiology

Humans

Infection Control

Korea

Middle East*

Public Health*

Quarantine

Saudi Arabia

Temefos

Triage

Visitors to Patients

Temefos

Figure

Cited by 5 articles

-

Lessons learned from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus cluster in Korea

Jae Wook Choi

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(7):595-597. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.595.Emergency medical services in response to the middle east respiratory syndrome outbreak in Korea

Kang Hyun Lee

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(7):611-616. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.611.Public health crisis response and establishment of a crisis communication system in South Korea: lessons learned from the MERS outbreak

Jae Wook Choi, Kyung Hee Kim, Jiwon Monica Moon, Min Soo Kim

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(7):624-634. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.624.Healthcare workers infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and infection control

Soo Geun Kim

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(7):647-654. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.7.647.Proposed Master Plan for Reform of the National Infectious Disease Prevention and Management System in Korea

Jae Wook Choi, Jin Seok Lee, Kye Hyun Kim, Cheong Hee Kang, Ho Kee Yum, Yoon Kim, Kang Hyun Lee, In Seok Seo, Ick Gang Rim, Dong Ho Oh, Jung Chan Lee, Kyung Hwa Seo, Seok Yeong Kim

J Korean Med Assoc. 2015;58(8):723-728. doi: 10.5124/jkma.2015.58.8.723.

Reference

-

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East respiratory syndrome information [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.mers.go.kr/mers/html/jsp/main.jsp.2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Updated rapid risk assessment: severe disease associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), 15th update [Internet]. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/coronavirus-infections/Pages/publications.aspx.3. Oboho IK, Tomczyk SM, Al-Asmari AM, Banjar AA, Al-Mugti H, Aloraini MS, Alkhaldi KZ, Almohammadi EL, Alraddadi BM, Gerber SI, Swerdlow DL, Watson JT, Madani TA. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah: a link to health care facilities. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:846–854.

Article4. Hinds W. Aerosol technology: properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley;1999.5. Aliabadi AA, Rogak SN, Bartlett KH, Green SI. Preventing airborne disease transmission: review of methods for ventilation design in health care facilities. Adv Prev Med. 2011; 2011:124064.

Article6. La Rosa G, Fratini M, Della Libera S, Iaconelli M, Muscillo M. Viral infections acquired indoors through airborne, droplet or contact transmission. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2013; 49:124–132.7. Fernstrom A, Goldblatt M. Aerobiology and its role in the transmission of infectious diseases. J Pathog. 2013; 2013:493960.

Article8. Byers R, Medley SR, Dickens ML, Hofacre KC, Samsonow MA, van Hoek ML. Transfer and reaerosolization of biological contaminant following field technician servicing of an aerosol sampler. J Bioterror Biodef. 2013; S3:011.9. Tellier R. Review of aerosol transmission of influenza A virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006; 12:1657–1662.

Article10. Baron P. Generation and behavior of airborne particles (aerosols)/aerosol 101 [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2010. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aerosols/default.html.11. Hui DS, Chow BK, Chu LC, Ng SS, Hall SD, Gin T, Chan MT. Exhaled air and aerosolized droplet dispersion during application of a jet nebulizer. Chest. 2009; 135:648–654.

Article12. Morawska L. Droplet fate in indoor environments, or can we prevent the spread of infection? Indoor Air. 2006; 16:335–347.

Article13. Tang JW, Li Y, Eames I, Chan PK, Ridgway GL. Factors involved in the aerosol transmission of infection and control of ventilation in healthcare premises. J Hosp Infect. 2006; 64:100–114.14. Chao CY, Wan MP, Morawska L, Johnson GR, Ristovski ZD, Hargreaves M, Mengersen K, Corbett S, Li Y, Xie X, Katoshevski D. Characterization of expiration air jets and droplet size distributions immediately at the mouth opening. J Aerosol Sci. 2009; 40:122–133.

Article15. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for management of MERS. 2nd ed. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014.16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for healthcare professionals [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2014. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/hcp/home-care-patient.html.17. Azhar EI, Hashem AM, El-Kafrawy SA, Sohrab SS, Aburizaiza AS, Farraj SA, Hassan AM, Al-Saeed MS, Jamjoom GA, Madani TA. Detection of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus genome in an air sample originating from a camel barn owned by an infected patient. MBio. 2014; 5:e01450-14.

Article18. Butler D. South Korean MERS outbreak is not a global threat [Internet]. [place unknown]: Nature News;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.nature.com/news/southkorean-mers-outbreak-is-not-a-global-threat-1.17709.19. World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): update [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2014. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2014_04_11_mers/en/#.20. Woolhouse ME, Dye C, Etard JF, Smith T, Charlwood JD, Garnett GP, Hagan P, Hii JL, Ndhlovu PD, Quinnell RJ, Watts CH, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM. Heterogeneities in the transmission of infectious agents: implications for the design of control programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94:338–342.

Article21. Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005; 438:355–359.

Article22. Shen Z, Ning F, Zhou W, He X, Lin C, Chin DP, Zhu Z, Schuchat A. Superspreading SARS events, Beijing, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:256–260.

Article23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Singapore, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003; 52:405–411.24. Gopalakrishna G, Choo P, Leo YS, Tay BK, Lim YT, Khan AS, Tan CC. SARS transmission and hospital containment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:395–400.

Article25. Chan KP. Control of severe acute respiratory syndrome in singapore. Environ Health Prev Med. 2005; 10:255–259.

Article26. Le DH, Bloom SA, Nguyen QH, Maloney SA, Le QM, Leitmeyer KC, Bach HA, Reynolds MG, Montgomery JM, Comer JA, Horby PW, Plant AJ. Lack of SARS transmission among public hospital workers, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004; 10:265–268.

Article27. Eichenwald HF, Kotsevalov O, Fasso LA. The "cloud baby": an example of bacterial-viral interaction. Am J Dis Child. 1960; 100:161–173.

Article28. Bassetti S, Bassetti-Wyss B, D'Agostino R, Gwaltney JM, Pfaller MA, Sherertz RJ. 'Cloud adults' exist: airborne dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus associated with a rhinovirus infection. In : Infectious Diseases Society of America. 38th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2000 Sep 7-10; New Orleans, LA, USA. Arlington: Infectious Diseases Society of America;2000.29. Bassetti S, Bischoff WE, Walter M, Bassetti-Wyss BA, Mason L, Reboussin BA, D'Agostino RB Jr, Gwaltney JM Jr, Pfaller MA, Sherertz RJ. Dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus into the air associated with a rhinovirus infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005; 26:196–203.

Article30. Sherertz RJ, Reagan DR, Hampton KD, Robertson KL, Streed SA, Hoen HM, Thomas R, Gwaltney JM Jr. A cloud adult: the Staphylococcus aureus-virus interaction revisited. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 124:539–547.

Article31. Stein RA. Super-spreaders in infectious diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2011; 15:e510–e513.

Article32. World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) summary and literature update as of 22 November 2013 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;2013. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/Update12_MERSCoV_update_22Nov13.pdf.33. Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Van Kerkhove MD, Donnelly CA, Riley S, Rambaut A, Enouf V, van der Werf S, Ferguson NM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance bias, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014; 14:50–56.

Article34. Li Y, Yu IT, Xu P, Lee JH, Wong TW, Ooi PL, Sleigh AC. Predicting super spreading events during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemics in Hong Kong and Singapore. Am J Epidemiol. 2004; 160:719–728.

Article35. Breban R, Riou J, Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013; 382:694–699.

Article36. Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Barrak A, Flemban H, Al-Nassir WN, Balkhy HH, Al-Hakeem RF, Makhdoom HQ, Zumla AI, Memish ZA. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013; 13:752–761.

Article37. Yu DY, Lee WS. All deceased were chronic disease patients. No need to be anxious [Internet]. Seoul: Dong A Science;2015. cited 2015 June 10. Available from: http://www.dongascience.com/news/view/7221/special/.38. Lee CH. The biggest outbreak outside of the Middle East... Why? [Internet]. Seoul: KBS NEWS;2015. cited 2015 June 10. Available from: http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/NewsView.do?SEARCH_NEWS_CODE=3083801.39. Harriman K, Brosseau L, Trivedi K. Hospital-associated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1761.

Article40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for hospitalized patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/infection-prevention-control.html.41. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing home care and isolation or quarantine of people not requiring hospitalization for MERS-CoV [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/hcp/home-care.html.42. MERS: the latest threat to global health security. Lancet. 2015; 385:2324.43. World Health Organization Western Pacific Region. WHO Korean MERS joint mission: high level messages [Internet]. Manila: World Health Organization Western Pacific Region;2015. cited 2015 June 12. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/mers-hlmsg/en/.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Same Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) yet Different Outbreak Patterns and Public Health Impacts on the Far East Expert Opinion from the Rapid Response Team of the Republic of Korea

- A New Measure for Assessing the Public Health Response to a Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Outbreak

- An Unexpected Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection in the Republic of Korea, 2015

- Public health crisis response and establishment of a crisis communication system in South Korea: lessons learned from the MERS outbreak

- Surveillance operation for the 141st confirmed case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus in response to the patient's prior travel to Jeju Island