Korean J Urol.

2014 Nov;55(11):725-731. 10.4111/kju.2014.55.11.725.

What Is the Ideal Core Number for Ultrasound-Guided Prostate Biopsy?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Graduate in Base of Surgery Program, Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University, Botucatu, Sao Paulo, Brazil. renato.chambo@gmail.com

- 2Department of Pathology, Hospital das Clinicas, Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University, Botucatu, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- 3Department of Urology, Hospital das Clinicas, Botucatu Medical School, Sao Paulo State University, Botucatu, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- KMID: 2069914

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4111/kju.2014.55.11.725

Abstract

- PURPOSE

We evaluated the utility of 10-, 12-, and 16-core prostate biopsies for detecting prostate cancer (PCa) and correlated the results with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, prostate volumes, Gleason scores, and detection rates of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) and atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

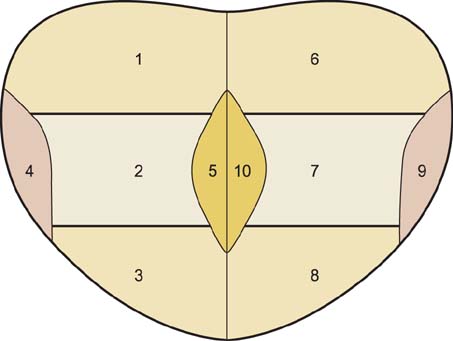

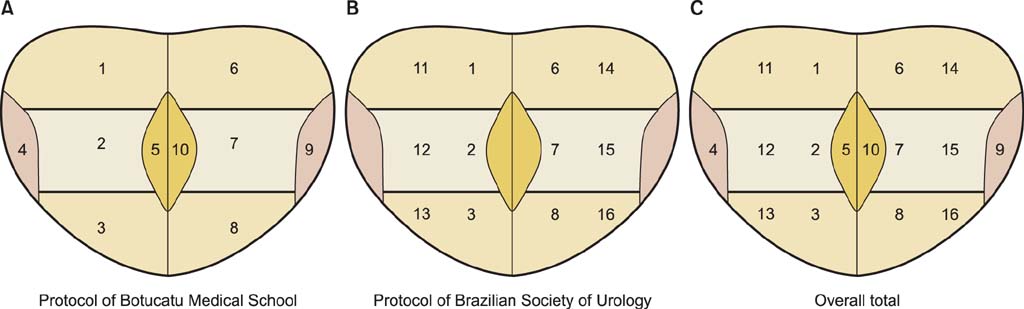

A prospective controlled study was conducted in 354 consecutive patients with various indications for prostate biopsy. Sixteen-core biopsy specimens were obtained from 351 patients. The first 10-core biopsy specimens were obtained bilaterally from the base, middle third, apex, medial, and latero-lateral regions. Afterward, six additional punctures were performed bilaterally in the areas more lateral to the base, middle third, and apex regions, yielding a total of 16-core biopsy specimens. The detection rate of carcinoma in the initial 10-core specimens was compared with that in the 12- and 16-core specimens.

RESULTS

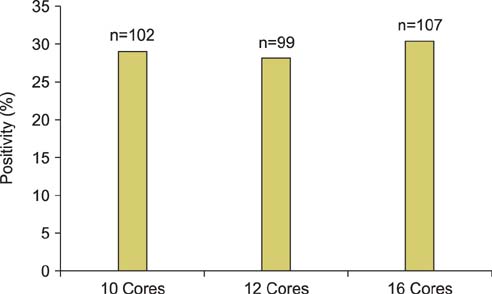

No significant differences in the cancer detection rate were found between the three biopsy protocols. PCa was found in 102 patients (29.06%) using the 10-core protocol, in 99 patients (28.21%) using the 12-core protocol, and in 107 patients (30.48%) using the 16-core protocol (p=0.798). The 10-, 12-, and 16-core protocols were compared with stratified PSA levels, stratified prostate volumes, Gleason scores, and detection rates of HGPIN and ASAP; no significant differences were found.

CONCLUSIONS

Cancer positivity with the 10-core protocol was not significantly different from that with the 12- and 16-core protocols, which indicates that the 10-core protocol is acceptable for performing a first biopsy.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

-

Adult

Aged

Cell Proliferation

Endosonography/*methods

Equipment Design

Follow-Up Studies

Humans

Image-Guided Biopsy/*instrumentation

Male

Middle Aged

Neoplasm Grading

Neoplasm Staging

Prospective Studies

Prostate/metabolism/pathology

Prostate-Specific Antigen/metabolism

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia/metabolism/*pathology

Prostatic Neoplasms/metabolism/*pathology

Rectum

Reproducibility of Results

Prostate-Specific Antigen

Figure

Reference

-

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014; 64:9–29.2. Estimativa 2014 - Incidência de câncer no Brasil [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional do Câncer;2014. cited 2011 Jun 1. Available from: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/prostata.3. Faria EF, Carvalhal GF, Vieira RA, Silva TB, Mauad EC, Carvalho AL. Program for prostate cancer screening using a mobile unit: results from Brazil. Urology. 2010; 76:1052–1057.4. Escudero Bregante JF, Lopez Cubillana P, Cao Avellaneda E, Lopez Lopez AI, Maluff Torres A, Lopez Gonzalez PA, et al. Clinical efficacy of prostatic biopsy. Experience in our center from 1990 to 2002. Actas Urol Esp. 2008; 32:713–716.5. Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations. Prostate. 1983; 4:473–485.6. Hodge KK, McNeal JE, Terris MK, Stamey TA. Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol. 1989; 142:71–74.7. Levine MA, Ittman M, Melamed J, Lepor H. Two consecutive sets of transrectal ultrasound guided sextant biopsies of the prostate for the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998; 159:471–475.8. Eskew LA, Bare RL, McCullough DL. Systematic 5 region prostate biopsy is superior to sextant method for diagnosing carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol. 1997; 157:199–202.9. Presti JC Jr, Chang JJ, Bhargava V, Shinohara K. The optimal systematic prostate biopsy scheme should include 8 rather than 6 biopsies: results of a prospective clinical trial. J Urol. 2000; 163:163–166.10. Naughton CK, Miller DC, Mager DE, Ornstein DK, Catalona WJ. A prospective randomized trial comparing 6 versus 12 prostate biopsy cores: impact on cancer detection. J Urol. 2000; 164:388–392.11. Presti JC Jr. Prostate biopsy strategies. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007; 4:505–511.12. Lane BR, Zippe CD, Abouassaly R, Schoenfield L, Magi-Galluzzi C, Jones JS. Saturation technique does not decrease cancer detection during followup after initial prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2008; 179:1746–1750.13. Jones JS, Patel A, Schoenfield L, Rabets JC, Zippe CD, Magi-Galluzzi C. Saturation technique does not improve cancer detection as an initial prostate biopsy strategy. J Urol. 2006; 175:485–488.14. Pepe P, Aragona F. Saturation prostate needle biopsy and prostate cancer detection at initial and repeat evaluation. Urology. 2007; 70:1131–1135.15. Nomikos M, Karyotis I, Phillipou P, Constadinides C, Delakas D. The implication of initial 24-core transrectal prostate biopsy protocol on the detection of significant prostate cancer and high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Int Braz J Urol. 2011; 37:87–93.16. Ceylan C, Doluoglu OG, Aglamis E, Baytok O. Comparison of 8, 10, 12, 16, 20 cores prostate biopsies in the determination of prostate cancer and the importance of prostate volume. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014; 8:E81–E85.17. Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, Busby JE, D'Amico A, Eastham JA, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010; 8:162–200.18. Yoon BI, Shin TS, Cho HJ, Hong SH, Lee JY, Hwang TK, et al. Is it effective to perform two more prostate biopsies according to prostate-specific antigen level and prostate volume in detecting prostate cancer? Prospective study of 10-core and 12-core prostate biopsy. Urol J. 2012; 9:491–497.19. Mariappan P, Chong WL, Sundram M, Mohamed SR. Increasing prostate biopsy cores based on volume vs the sextant biopsy: a prospective randomized controlled clinical study on cancer detection rates and morbidity. BJU Int. 2004; 94:307–310.20. Remzi M, Fong YK, Dobrovits M, Anagnostou T, Seitz C, Waldert M, et al. The Vienna nomogram: validation of a novel biopsy strategy defining the optimal number of cores based on patient age and total prostate volume. J Urol. 2005; 174(4 Pt 1):1256–1260.21. Lecuona A, Heyns CF. A prospective, randomized trial comparing the Vienna nomogram to an eight-core prostate biopsy protocol. BJU Int. 2011; 108:204–208.22. Naya Y, Ochiai A, Troncoso P, Babaian RJ. A comparison of extended biopsy and sextant biopsy schemes for predicting the pathological stage of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004; 171(6 Pt 1):2203–2208.23. Mian BM, Lehr DJ, Moore CK, Fisher HA, Kaufman RP Jr, Ross JS, et al. Role of prostate biopsy schemes in accurate prediction of Gleason scores. Urology. 2006; 67:379–383.24. Leite KR, Srougi M, Dall'Oglio MF, Sanudo A, Camara-Lopes LH. Histopathological findings in extended prostate biopsy with PSA < or = 4 ng/mL. Int Braz J Urol. 2008; 34:283–290.25. Ploussard G, Plennevaux G, Allory Y, Salomon L, Azoulay S, Vordos D, et al. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and atypical small acinar proliferation on initial 21-core extended biopsy scheme: incidence and implications for patient care and surveillance. World J Urol. 2009; 27:587–592.26. Epstein JI, Potter SR. The pathological interpretation and significance of prostate needle biopsy findings: implications and current controversies. J Urol. 2001; 166:402–410.27. Iczkowski KA, Chen HM, Yang XJ, Beach RA. Prostate cancer diagnosed after initial biopsy with atypical small acinar proliferation suspicious for malignancy is similar to cancer found on initial biopsy. Urology. 2002; 60:851–854.28. Pelzer AE, Bektic J, Berger AP, Halpern EJ, Koppelstatter F, Klauser A, et al. Are transition zone biopsies still necessary to improve prostate cancer detection? Results from the tyrol screening project. Eur Urol. 2005; 48:916–921.29. Tsuji FH, Chambo RC, Agostinho AD, Trindade Filho JC, de Jesus CM. Sedoanalgesia with midazolam and fentanyl citrate controls probe pain during prostate biopsy by transrectal ultrasound. Korean J Urol. 2014; 55:106–111.30. de Jesus CM, Correa LA, Padovani CR. Complications and risk factors in transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsies. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006; 124:198–202.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pain during Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Prostate Biopsy and the Role of Periprostatic Nerve Block: What Radiologists Should Know

- Usefulness of Ultrasound-Guided Automated Core Biopsy of Nonpalpable Breast Lesions

- Can a 12 Core Prostate Biopsy Increase the Detection Rate of Prostate Cancer versus 6 Core?: A Prospective Randomized Study in Korea

- Medially Directed TRUS Biopsy of the Prostate: Clinical Utility and Optimal Protocol

- Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Prostate Biopsy: Current Status and Controversy