Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2015 Sep;58(5):414-417. 10.5468/ogs.2015.58.5.414.

Intrapelvic dissemination of early low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma due to electronic morcellation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Catholic University of Daegu School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. drcys@cu.ac.kr

- KMID: 2058468

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2015.58.5.414

Abstract

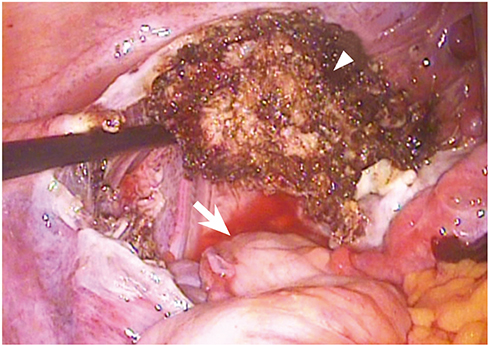

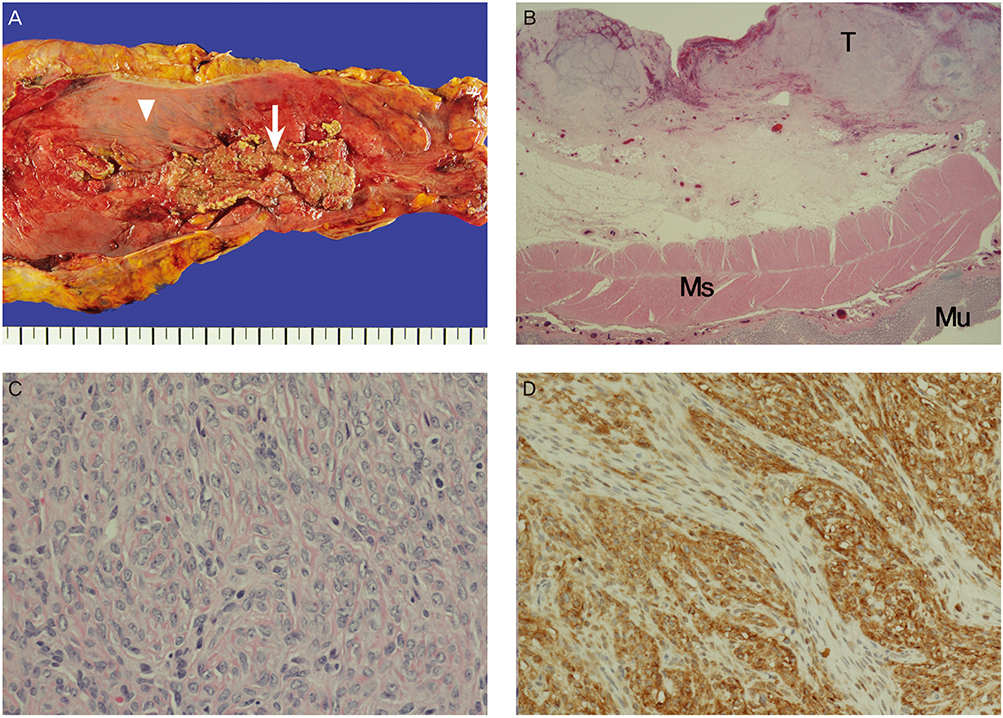

- Endometrioid stromal sarcoma is a rare malignancy that originates from mesenchymal cells. It is classified into low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma (LGESS) and high-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma. Ultrasonographic findings of LGESS resemble those of submucosal myomas, leading to the possible preoperative misdiagnosis of LGESS as uterine leiomyoma. Electronic morcellation during laparoscopic surgery in women with LGESS can result in iatrogenic intraabdominal dissemination and a poorer prognosis. Here, we report a patient with LGESS who underwent a supracervical hysterectomy and electronic morcellation for a presumed myoma in another hospital. Disseminated metastatic lesions of LGESS in the posterior cul-de-sac and rectal serosal surface were absent on primary surgery, but found during reexploration. In conclusion, when LGESS is found incidentally following previous morcellation during laparoscopic surgery for presumed benign uterine disease, we highly recommend surgical reexploration, even when there is no evidence of a metastatic lesion in imaging studies.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumors of the female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon (FR): World Health Organization Publisher;2014.2. Rauh-Hain JA, del Carmen MG. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122:676–683.3. Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the outcomes of patients with apparently early low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011; 18:3453–3461.4. US Food and Drug Administration. Quantitative assessment of the prevalence of unsuspected uterine sarcoma in women undergoing treatment of uterine fibroids [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration;c2014. cited 2014 Apr 17. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/.../UCM393589.pdf.5. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic uterine power morcellation in hysterectomy and myomectomy: FDA safety communication [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration;c2014. cited 2014 Nov 24. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm424443.htm.6. Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014; 311:905–906.7. Einstein MH, Barakat RR, Chi DS, Sonoda Y, Alektiar KM, Hensley ML, et al. Management of uterine malignancy found incidentally after supracervical hysterectomy or uterine morcellation for presumed benign disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008; 18:1065–1070.8. Oduyebo T, Rauh-Hain AJ, Meserve EE, Seidman MA, Hinchcliff E, George S, et al. The value of re-exploration in patients with inadvertently morcellated uterine sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2014; 132:360–365.9. Leung F, Terzibachian JJ, Gay C, Chung Fat B, Aouar Z, Lassabe C, et al. Hysterectomies performed for presumed leiomyomas: should the fear of leiomyosarcoma make us apprehend non laparotomic surgical routes? Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009; 37:109–114.10. Malouf GG, Duclos J, Rey A, Duvillard P, Lazar V, Haie-Meder C, et al. Impact of adjuvant treatment modalities on the management of patients with stages I-II endometrial stromal sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21:2102–2106.11. Park JY, Park SK, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011; 122:255–259.12. Della Badia C, Karini H. Endometrial stromal sarcoma diagnosed after uterine morcellation in laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010; 17:791–793.13. Nam JH, Park JY. Update on treatment of uterine sarcoma. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 22:36–42.14. Einarsson JI, Cohen SL, Fuchs N, Wang KC. In-bag morcellation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014; 21:951–953.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Two Cases of Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

- Two Cases of Low Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

- Treatment of Low Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

- A Case of Low-Grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma of the Uterus (So-Called ""Endolymphatic Stromal Myosis"")

- A Case of Endometrioid Stromal Sarcoma of ovary