Healthc Inform Res.

2012 Jun;18(2):115-124. 10.4258/hir.2012.18.2.115.

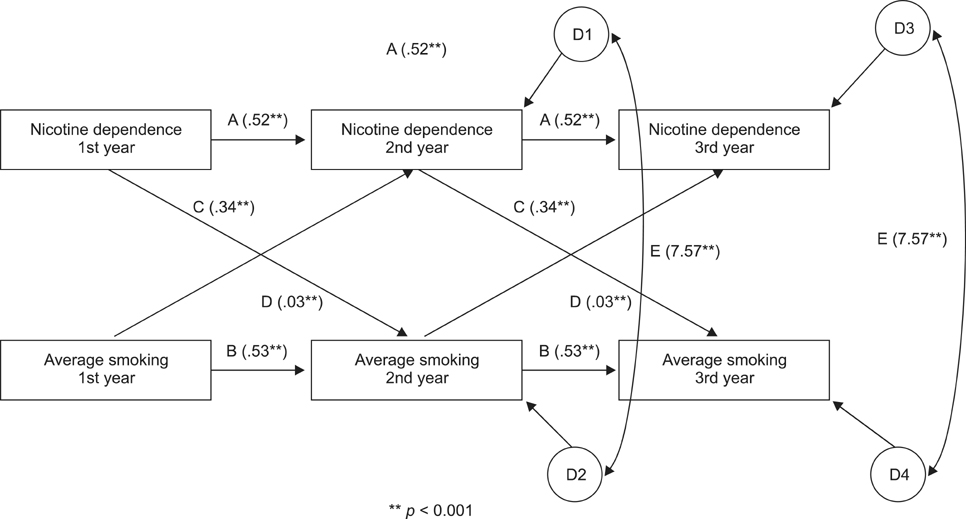

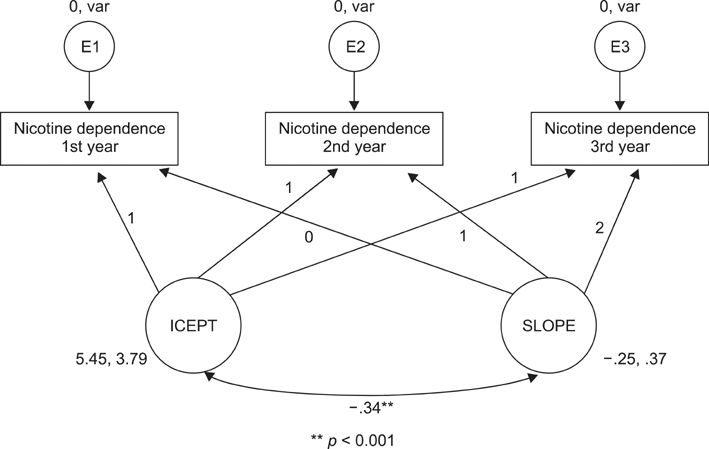

A Three-Year Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis on Nicotine Dependence and Average Smoking

- Affiliations

-

- 1U-Health & Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Seoul, Korea.

- 2u-Healthcare Design Institute, Inje University, Seoul, Korea. ajy0130@inje.ac.kr

- 3College of Nursing & Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA, USA.

- 4Department of Business Administration, Semyung University, Jechon, Korea.

- 5Department of Health Administration, Namseoul University, Cheonan, Korea.

- 6Department of Medical Informatics & Management, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea.

- KMID: 2045575

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2012.18.2.115

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Previous studies have been limited to the use of cross sectional data to identify the relationships between nicotine dependence and smoking. Therefore, it is difficult to determine a causal direction between the two variables. The purposes of this study were to 1) test whether nicotine dependence or average smoking was a more influential factor in smoking cessation; and 2) propose effective ways to quit smoking as determined by the causal relations identified.

METHODS

This study used a panel dataset from the central computerized management systems of community-based smoking cessation programs in Korea. Data were stored from July 16, 2005 to July 15, 2008. 711,862 smokers were registered and re-registered for the programs during the period. 860 of those who were retained in the programs for three years were finally included in the dataset. To measure nicotine dependence, this study used a revised Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. To examine the relationship between nicotine dependence and average smoking, an autoregressive cross-lagged model was explored in the study.

RESULTS

The results indicate that 1) nicotine dependence and average smoking were stable over time; 2) the impact of nicotine dependence on average smoking was significant and vice versa; and 3) the impact of average smoking on nicotine dependence is greater than the impact of nicotine dependence on average smoking.

CONCLUSIONS

These results support the existing data obtained from previous research. Collectively, reducing the amount of smoking in order to decrease nicotine dependence is important for evidence-based policy making for smoking cessation.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Benowitz NL. Drug therapy. Pharmacologic aspects of cigarette smoking and nicotine addition. N Engl J Med. 1988. 319:1318–1330.2. Benowitz NL. Neurobiology of nicotine addiction: implications for smoking cessation treatment. Am J Med. 2008. 121:S3–S10.

Article3. Benowitz NL, Jacob P 3rd. Daily intake of nicotine during cigarette smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984. 35:499–504.

Article4. Song TM, Lee JY, An JY. Changes in smoking practices and the process of nicotine dependence. J Korean Soc Health Educ Promot. 2010. 27:123–129.5. Grunberg NE, Winders SE, Wewers ME. Gender differences in tobacco use. Health Psychol. 1991. 10:143–153.

Article6. Rosenbaum P, O'Shea R. Large-scale study of freedom from smoking clinics: factors in quitting. Public Health Rep. 1992. 107:150–155.7. Rigotti NA. Clinical practice. Treatment of tobacco use and dependence. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346:506–512.8. Carlson LE, Taenzer P, Koopmans J, Bultz BD. Eight-year follow-up of a community-based large group behavioral smoking cessation intervention. Addict Behav. 2000. 25:725–741.

Article9. Balfour D, Benowitz N, Fagerstrom K, Kunze M, Keil U. Diagnosis and treatment of nicotine dependence with emphasis on nicotine replacement therapy: a status report. Eur Heart J. 2000. 21:438–445.

Article10. Levshin V, Radkevich N, Slepchenko N, Droggachih V. Implementation and evaluation of a smoking cessation group session program. Prevent Control. 2006. 2:39–47.

Article11. Lee ES, Seo HG. The factors associated with successful smoking cessation in Korea. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2007. 28:39–44.12. Suh KH, Kim KH, Jun ID. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy and nicotine replacement therapy centered smoking intervention and abstention factors. Korean J Health Psychol. 2008. 13:705–726.

Article13. Song TM, Lee JY, Cho KS. The factors Influencing on success of quitting smoking in new enrollees and re-enrollees in smoking cessation clinics. J Korean Soc Health Educ Promot. 2008. 25:19–30.14. Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Hops H, Brigham J, Hudmon KS, Andrews JA, Tildesley E, McBride D, Jack LM, Javitz HS, Swan GE. Adolescent smoking trajectories and nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008. 10:341–351.

Article15. Everett SA, Warren CW, Sharp D, Kann L, Husten CG, Crossett LS. Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among U.S. high school students. Prev Med. 1999. 29:327–333.

Article16. Lando HA, Thai DT, Murray DM, Robinson LA, Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Hennrikus DJ. Age of initiation, smoking patterns, and risk in a population of working adults. Prev Med. 1999. 29:590–598.

Article17. Robinson ML, Berlin I, Moolchan ET. Tobacco smoking trajectory and associated ethnic differences among adolescent smokers seeking cessation treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2004. 35:217–224.

Article18. Park S, Lee JY, Song TM, Cho SI. Age-associated changes in nicotine dependence. Public Health. 2012. 126:482–489.

Article19. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991. 86:1119–1127.

Article20. Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models a synthesis of two traditions. Sociol Methods Res. 2004. 32:336–383.

Article21. Hong SH, Park MS, Kim WJ. Testing the autoregressive cross-lagged effects between adolescents' internet addiction and communication with parents: multigroup analysis across gender. Korean J Educ Psychol. 2007. 21:129–143.22. Krus DJ, Blackman HS. Test reliability and homogeneity from the perspective of the ordinal test theory. Appl Meas Educ. 1988. 1:79–88.

Article23. Wikipedia. Homogeneity (statistics) [Internet]. c2012. cited at 2012 May 4. San Francisco, CA: Wikipedia Foundation Inc.;Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homogeneity_(statistics).24. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999. 6:1–55.

Article25. Riddon EE. CFI versus RMSEA: a comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling. 1996. 3:369–379.

Article26. Woo JP. The concept and understanding of structural equation modeling. 2012. Seoul, Korea: Hannarae Academy;366.27. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Alternative ways of accessing model fit. Testing structural equation models. 1993. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications;136–162.28. MacCallum RC, Browne MW. The use of causal indicators in covariance structure models: some practical issues. Psychol Bull. 1993. 114:533–541.

Article29. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2010. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press;63.30. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981. 18:39–50.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Longitudinal Relationship Between Smartphone Dependence and Externalizing Behavior Problems: An Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Model

- The Longitudinal Relationships between Depression and Smoking in Hardcore Smokers Using Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Modeling

- The Comorbidity of Alcohol Dependence and Nicotine Dependence

- Cigarette Smoking, Stage of Smoking Cessation, Nicotine Dependency, and Urine Nicotine Among Smoking Adults with Diabetes

- Smoking Related Factors according to the Nicotine Content