Korean J Obstet Gynecol.

2011 Apr;54(4):171-174. 10.5468/KJOG.2011.54.4.171.

Compare the architectural differences in the bony pelvis of Korean women and their association with the mode of delivery by computed tomography

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Catholic University of Korea School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. poouh74@catholic.ac.kr

- KMID: 2013229

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/KJOG.2011.54.4.171

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We investigated the structural differences in the pelvic bone architecture of Korean women and their association with the mode of delivery by performing computed tomography (CT) pelvimetry.

METHODS

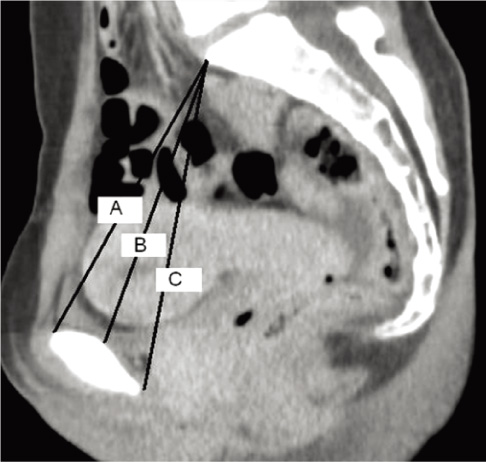

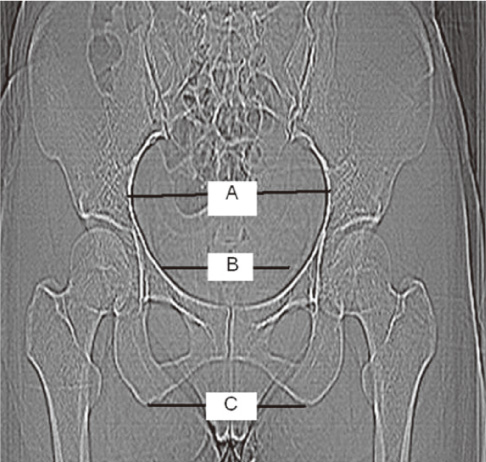

This study was conducted on 175 women who underwent CT between March of 2006 and May of 2008. For making an objective assessment, one specialist in obsterics and gynecology measured the obstetrical conjugate, the true conjugate and the diagonal conjugate on the sagittal plane and the transverse diameter, the intertuberous diameter and the interspinous diameter on the coronal plane. The patients who underwent total hysterectomy or those who had a disease of the uterus were excluded from the current analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 175 Korean women were examined, and their ages ranged from 20 to 50 years. The mean age was 37.6 +/- 7.4 years. The interspinous diameter that was measured on CT scans was 94.6 +/- 7.8 mm in the vaginal delivery group (n=84) and this was 90.9 +/- 6.6 mm in the cesarean section group (n=20). This difference reached statistical significance.

CONCLUSION

Our study examined the difference in the pelvic architecture with using CT and we found that the interspinous diameter can be the important determinant that affects normal vaginal delivery. Of these pelvimetric parameters, a wider interspinous diameter was significantly associated with vaginal delivery. Multi-displinary approaches are warranted to examine this relation with regard to the various factors that are involved in delivery.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nichols DH, Randall CL. Vaginal surgery. 1996. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.2. Federle MP, Cohen HA, Rosenwein MF, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Cann CE. Pelvimetry by digital radiography: a low-dose examination. Radiology. 1982. 143:733–735.3. Gimovsky ML, Willard K, Neglio M, Howard T, Zerne S. X-ray pelvimetry in a breech protocol: a comparison of digital radiography and conventional methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 153:887–888.4. Hankins GDV, Clark SL, Cunningham FG, Gilstrap LC III. Operative obstetrics. 1995. Norwalk (CT): Appleton & Lange.5. Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 2005. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.6. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JH, Rouse DJ, Spong GY. Williams obstetrics. 2010. 23rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.7. Anderson N, Humphries N, Wells JE. Measurement error in computed tomography pelvimetry. Australas Radiol. 2005. 49:104–107.8. Park KH, Park EJ, Kim WW. A clinical study of X-ray pelvimetry. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1982. 25:87–95.9. Pattinson RC. Pelvimetry for fetal cephalic presentations at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. (2):CD000161.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Correlation between Maternal Anteand Postpartum Depression and Mode of Delivery: Preliminary Study

- Comparative study on alveolar bone height of pantomography and multiplanar reformatted computed tomography

- Computed tomographic evaluation of the osseous pelvis

- The degree of labor pain at the time of epidural analgesia in nulliparous women influences the obstetric outcome

- Radiation absorbed doses of cone beam computed tomography