Neurointervention.

2014 Sep;9(2):78-82. 10.5469/neuroint.2014.9.2.78.

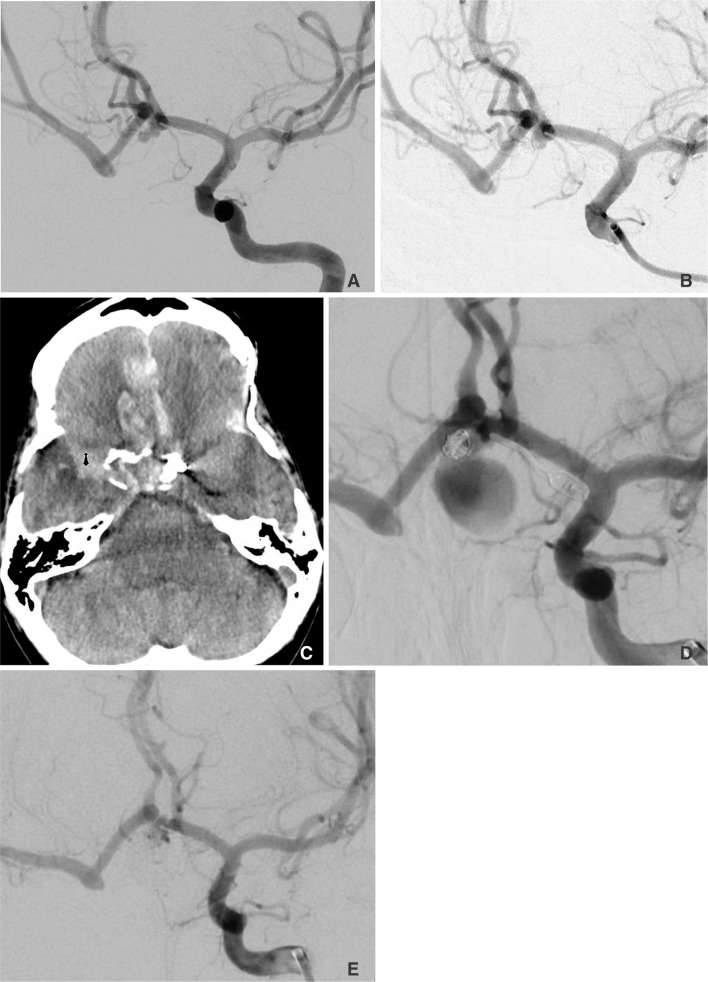

Spontaneous Internal Carotid Artery Occlusion and Rapid Cerebral Aneurysm Progression: Case Series and Literature Review

- Affiliations

-

- 1Departments of Neurological Surgery and Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA. Michael_Chen@rush.edu

- 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

- KMID: 1910762

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5469/neuroint.2014.9.2.78

Abstract

- PURPOSE

An accurate determination of the natural history of a cerebral aneurysm has implications on management. Few risk factors other than female gender and cigarette smoking have been identified to be associated with cerebral aneurysm progression, particularly rapid progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This case series and literature review serves to illustrate a relationship between spontaneous carotid occlusion and rapid enlargement of cerebral aneurysms.

RESULTS

In our case series, we demonstrated that increased hemodynamic stress on collateral vessels caused by a spontaneous carotid occlusion may contribute to unusually rapid aneurysm growth and/or rupture.

CONCLUSION

Spontaneous carotid occlusive disease may be considered a risk factor for rapid cerebral aneurysm progression and/or rupture that may warrant more aggressive management options, including more frequent surveillance imaging in previously treated aneurysms.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Sarti C, Tuomilehto J, Salomaa V, Sivenius J, Kaarsalo E, Narva EV, et al. Epidemiology of subarachnoid hemorrhage in finland from 1983 to 1985. Stroke. 1991; 22:848–853. PMID: 1853404.

Article2. Juvela S, Poussa K, Porras M. Factors affecting formation and growth of intracranial aneurysms: a long-term follow-up study. Stroke. 2001; 32:485–491. PMID: 11157187.3. Ostergaard JR. Risk factors in intracranial saccular aneurysms. Aspects on the formation and rupture of aneurysms, and development of cerebral vasospasm. Acta Neurol Scand. 1989; 80:81–98. PMID: 2683556.4. Longstreth WT Jr, Nelson LM, Koepsell TD, van Belle G. Cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1992; 23:1242–1249. PMID: 1519278.

Article5. Juvela S, Hillbom M, Numminen H, Koskinen P. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1993; 24:639–646. PMID: 8488517.

Article6. Alnaes MS, Isaksen J, Mardal KA, Romner B, Morgan MK, Ingebrigtsen T. Computation of hemodynamics in the circle of willis. Stroke. 2007; 38:2500–2505. PMID: 17673714.

Article7. Castro MA, Putman CM, Sheridan MJ, Cebral JR. Hemodynamic patterns of anterior communicating artery aneurysms: a possible association with rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009; 30:297–302. PMID: 19131411.

Article8. Eldawoody H, Shimizu H, Kimura N, Saito A, Nakayama T, Takahashi A, et al. Simplified experimental cerebral aneurysm model in rats: comprehensive evaluation of induced aneurysms and arterial changes in the circle of Willis. Brain Res. 2009; 1300:159–168. PMID: 19747458.

Article9. Meng H, Wang Z, Hoi Y, Gao L, Metaxa E, Swartz DD, et al. Complex hemodynamics at the apex of an arterial bifurcation induces vascular remodeling resembling cerebral aneurysm initiation. Stroke. 2007; 38:1924–1931. PMID: 17495215.

Article10. Chatziprodromou I, Tricoli A, Poulikakos D, Ventikos Y. Haemodynamics and wall remodelling of a growing cerebral aneurysm: a computational model. J Biomech. 2007; 40:412–426. PMID: 16527284.

Article11. Gonzalez CF, Cho YI, Ortega HV, Moret J. Intracranial aneurysms: flow analysis of their origin and progression. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992; 13:181–188. PMID: 1595440.12. Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:928–939. PMID: 16943405.

Article13. de Weerd M, Greving JP, Hedblad B, Lorenz MW, Mathiesen EB, O'Leary DH, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in the general population: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke. 2010; 41:1294–1297. PMID: 20431077.

Article14. van Everdingen KJ, Klijn CJ, Kappelle LJ, Mali WP, van der Grond J. The Dutch EC-IC By pass study Group. MRA flow quantification in patients with a symptomatic internal carotid artery occlusion. Stroke. 1997; 28:1595–1600. PMID: 9259755.

Article15. Arambepola PK, McEvoy SD, Bulsara KR. De novo aneurysm formation after carotid artery occlusion for cerebral aneurysms. Skull Base. 2010; 20:405–408. PMID: 21772796.

Article16. Timperman PE, Tomsick TA, Tew JM Jr, van Loveren HR. Aneurysm formation after carotid occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995; 16:329–331. PMID: 7726081.17. Dyste GN, Beck DW. De novo aneurysm formation following carotid ligation: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1989; 24:88–92. PMID: 2648178.

Article18. Jaffe ME, McHenry LC Jr. Cerebral aneurysm following spontaneous carotid occlusion. Neurology. 1968; 18:1012–1014. PMID: 5748745.

Article19. Klein O, Colnat-Coulbois S, Civit T, Auque J, Bracard S, Pinelli C, et al. Aneurysm clipping after endovascular treatment with coils: a report of 13 cases. Neurosurg Rev. 2008; 31:403–411. PMID: 18677524.

Article20. Gupta K, Radotra BD, Suri D, Sharma K, Saxena AK, Singhi P. Mycotic aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage following tubercular meningitis in an infant with congenital tuberculosis and cytomegalovirus disease. J Child Neurol. 2012; 27:1320–1325. PMID: 22433428.

Article21. Hurst RW, Judkins A, Bolger W, Chu A, Loevner LA. Mycotic aneurysm and cerebral infarction resulting from fungal sinusitis: imaging and pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001; 22:858–863. PMID: 11337328.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Cerebral Rete Mirabile with Intracranial Aneurysm

- Intracranial Aneurysm Associated with Aplasia of the Internal Cartoid Artery

- Spontaneous Recanalization from Traumatic Internal Carotid Artery Occlusion

- Supraclinoid Internal Carotid Artery Fenestration Harboring an Unruptured Aneurysm and Another Remote Ruptured Aneurysm: Case Report and Review of the Literature

- Giant Internal Carotid Artery Aneurysm:Posterior Cerebral Artery Territory Infarction After Ligation of the Right Internal Carotid Artery: Case Report