J Korean Med Sci.

2008 Oct;23(5):888-894. 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.5.888.

Effectiveness of Proactive Quitline Service and Predictors of Successful Smoking Cessation: Findings from a Preliminary Study of Quitline Service for Smoking Cessation in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Smoking Cessation Clinic and Center for Cancer Prevention and Detection, National Cancer Center & Cancer Prevention Branch, National Cancer Control Research Institute, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea. hongwan@ncc.re.kr

- 2Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine & Cancer Research Institute and Cancer Research Center, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1783078

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2008.23.5.888

Abstract

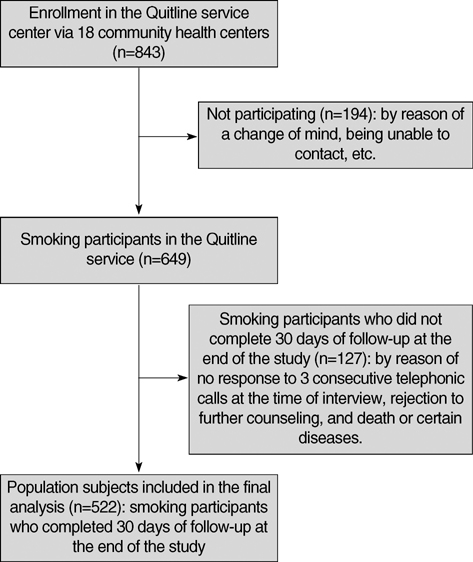

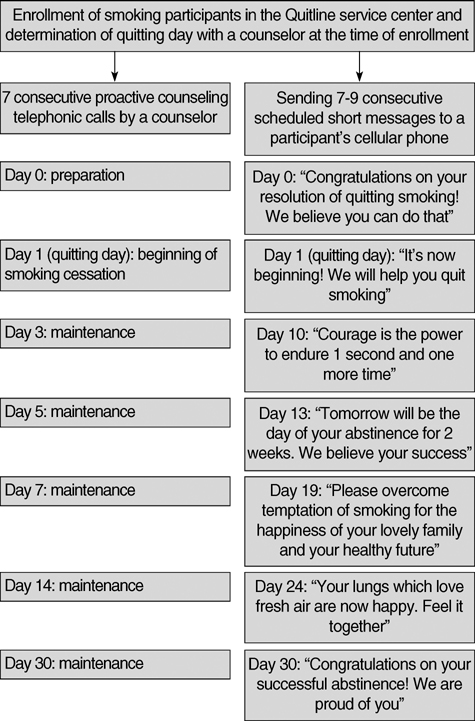

- This study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the first proactive Quitline service for smoking cessation in Korea and determine the predictors of successful smoking cessation. Smoking participants were voluntarily recruited from 18 community health centers. The participants were proactively counseled for smoking cessation via 7 sessions conducted for 30 days from November 1, 2005 to January 31, 2006. Of the 649 smoking participants, 522 completed 30 days at the end of the study and were included in the final analysis. The continuous abstinence rate at 30 days of follow-up was found to be 38.3% (200/522), in the intention-to-treat analysis. Compared with non-quitters, quitters were mostly male, smoked <20 cigarettes/ day, had started smoking at the age of > or =20 yr, and were less dependent on nicotine. Based on the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis, the significant predictors of successful smoking cessation were determined to be male sex, low cigarette consumption, and older age at smoking initiation. We investigated the short-term effectiveness of the Quitline service and determined the predictors of successful smoking cessation.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Owen L. Impact of a telephone helpline for smokers who called during a mass media campaign. Tob Control. 2000. 9:148–154.

Article2. Platt S, Tannahill A, Watson J, Fraser E. Effectiveness of antismoking telephone helpline: follow up survey. BMJ. 1997. 314:1371–1375.

Article3. Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, Rosbrook B, Johnson CE, Byrd M, Gutierrez-Terrell E. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002. 347:1087–1093.

Article4. An LC, Zhu SH, Nelson DB, Arikian NJ, Nugent S, Partin MR, Joseph AM. Benefits of telephone care over primary care for smoking cessation: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006. 166:536–542.5. Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. 3:CD002850.6. Pan W. Proactive telephone counseling as an adjunct to minimal intervention to for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Health Educ Res. 2006. 21:416–427.7. Jaen CR, Cummings KM, Zielezny M, O'Shea R. Patterns and predictors of smoking cessation among users of a telephone hotline. Public Health Rep. 1993. 108:772–778.8. Balanda KP, Lowe JB, O'Connor-Fleming ML. Comparison of two self-help smoking cessation booklets. Tob Control. 1999. 8:57–61.

Article9. Abdullah AS, Lam TH, Chan SS, Hedley AJ. Which smokers use the smoking cessation Quitline in Hong Kong, and how effective is the Quitline? Tob Control. 2004. 13:415–421.

Article10. Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychol Bull. 1992. 111:23–41.

Article11. SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002. 4:149–159.12. Lipkus IM, Lyna PR, Rimer BK. Using tailored interventions to enhance smoking cessation among African-Americans at a community health center. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999. 1:77–85.

Article13. Miller CL, Wakefield M, Roberts L. Uptake and effectiveness of the Australian telephone Quitline service in the context of a mass media campaign. Tob Control. 2003. 12:Suppl 2. ii53–ii58.

Article14. International Telecommunication Union. ITU ICT Eye: ICT Statistics 2006. Available at: www.itu.int/ITU-D/icteye/DisplayCountry.aspx?code=KOR.15. Glasgow RE, Mullooly JP, Vogt TM, Stevens VJ, Lichtenstein E, Hollis JF, Lando HA, Severson HH, Pearson KA, Vogt MR. Biochemical validation of smoking status: pros, cons, and data from four low-intensity intervention trials. Addict Behav. 1993. 18:511–527.

Article16. Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking; a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994. 84:1086–1093.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Success Factors for the Smoking Cessation Service of the Safe Pharmacy

- Self-efficacy and Preparation of Smoking Cessation in Service and Sales Woman Smokers Working in Department Stores

- Factors affecting the Success of Smoking Cessation for Six Months in the Smoking Cessation Clinic of a Public Health Center Based on the Trans-theoretical Model

- Physicians' Perspectives on the Smoking Cessation Service for Inpatient Smokers

- Effects of psychological conditions and changes on smoking cessation success after a residential smoking cessation therapy program: a retrospective observational study