Yonsei Med J.

2009 Jun;50(3):345-351. 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.3.345.

Self-Reported Exposure to Second-Hand Smoke and Positive Urinary Cotinine in Pregnant Nonsmokers

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 2Department of Obstetrics, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea.

- 3Smoking Cessation Clinic, Center for Cancer Prevention and Detection, Korea. msk@ncc.re.kr

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea.

- 5Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital; Preventive Medicine, Graduate School of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 1758561

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2009.50.3.345

Abstract

-

PURPOSE: This cross-sectional study aimed to examine the association between self-reported exposure status to second-hand smoke and urinary cotinine level in pregnant nonsmokers.

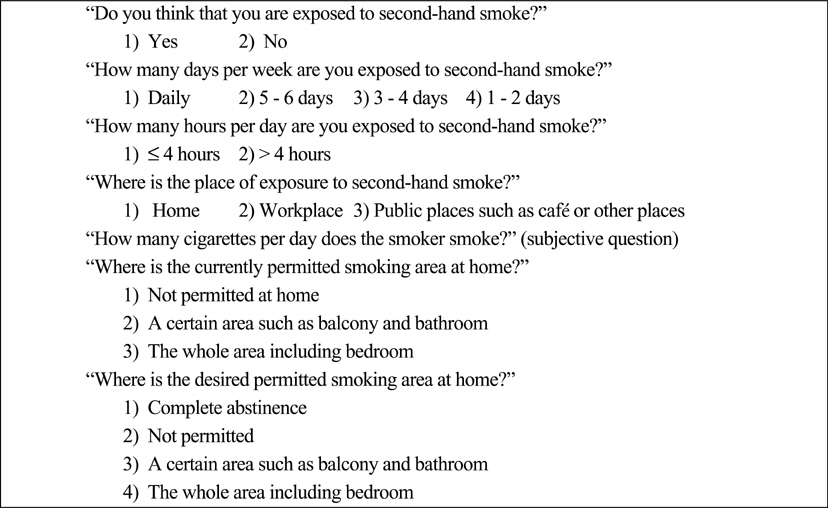

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We recruited pregnant nonsmokers from the prenatal care clinics of a university hospital and two community health centers, and their urinary cotinine concentrations were measured.

RESULTS

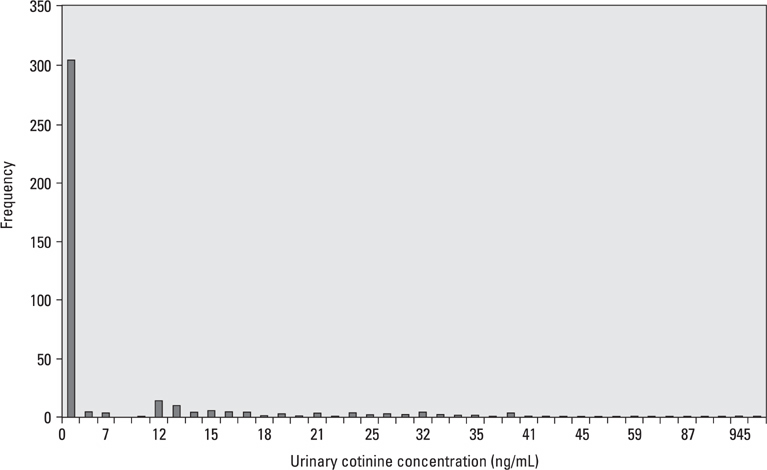

Among a total of 412 pregnant nonsmokers, the proportions of self-reported exposure to second-hand smoke and positive urinary cotinine level were 60.4% and 3.4%, respectively. Among those, 4.8% of the participants who reported exposure to second-hand smoke had cotinine levels of 40 ng/mL (the kappa value = 0.029, p = 0.049). Among those who reported living with smokers (n = 170), "smoking currently permitted in the whole house" (vs. not permitted at home) was associated with positive urinary cotinine in the univariable analysis. Furthermore, this variable showed a significant association with positive urinary cotinine in the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis [Odds ratio (OR), 15.6; 95% Confidence interval (CI) = 2.1-115.4].

CONCLUSION

In the current study, the association between self-reported exposure status to second-hand smoke and positive urinary cotinine in pregnant nonsmokers was poor. "Smoking currently permitted in the whole house" was a significant factor of positive urinary cotinine in pregnant nonsmokers. Furthermore, we suggest that a complete smoking ban at home should be considered to avoid potential adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes due to second-hand smoke.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ahluwalia IB, Grummer-Strawn L, Scanlon KS. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and birth outcome: increased effects on pregnant women aged 30 years or older. Am J Epidemiol. 1997. 146:42–47.

Article2. Windham GC, Hopkins B, Fenster L, Swan SH. Prenatal active or passive tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight. Epidemiology. 2000. 11:427–433.

Article3. Kharrazi M, DeLorenze GN, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT Jr, Graham S, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and pregnancy outcome. Epidemiology. 2004. 15:660–670.

Article4. Hegaard HK, Kjaergaard H, Møller LF, Wachmann H, Ottesen B. The effect of environmental tobacco smoke during pregnancy on birth weight. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006. 85:675–681.5. Moritsugu KP. The 2006 Report of the Surgeon General: the health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 2007. 32:542–543.

Article6. Rebagliato M, Bolumar F, Florey Cdu V. Assessment of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in nonsmoking pregnant women in different environments of daily living. Am J Epidemiol. 1995. 142:525–530.

Article7. O'Connor TZ, Holford TR, Leaderer BP, Hammond SK, Bracken MB. Measurement of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women. Am J Epidemiol. 1995. 142:1315–1321.8. DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women: the association between self-report and serum cotinine. Environ Res. 2002. 90:21–32.

Article9. George L, Granath F, Johansson AL, Cnattingius S. Self-reported nicotine exposure and plasma levels of cotinine in early and late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006. 85:1331–1337.

Article10. de Chazeron I, Llorca PM, Ughetto S, Coudore F, Boussiron D, Perriot J, et al. Occult maternal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Tob Control. 2007. 16:64–65.

Article11. Borland R, Mullins R, Trotter L, White V. Trends in environmental tobacco smoke restrictions in the home in Victoria, Australia. Tob Control. 1999. 8:266–271.

Article12. Johansson A, Hermansson G, Ludvigsson G. How should parents protect their children from environmental tobacco-smoke exposure in the home? Pediatrics. 2004. 113:e291–e295.13. Johansson A, Halling A, Hermansson G, Ludvigsson J. Assessment of smoking behaviors in the home and their influence on children's passive smoking: development of a questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 2005. 15:453–459.

Article14. Willemsen MC, Brug J, Uges DR, Vos de Wael ML. Validity and reliability of self-reported exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in work offices. J Occup Environ Med. 1997. 39:1111–1114.

Article15. Kaufman FL, Kharrazi M, Delorenze GN, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Estimation of environmental tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy using a single question on household smokers versus serum cotinine. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2002. 12:286–295.

Article16. Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiol Rev. 1996. 18:188–204.

Article17. Dempsey D, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz NL. Accelerated metabolism of nicotine and cotinine in pregnant smokers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002. 301:594–598.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Relationship between Passive Smoke and Urinary Cotinine Level

- Usefulness of Urinary Cotinine Test to Discriminate between Smokers and Nonsmokers in Korean Adolescents

- Association between secondhand smoke exposure and new-onset hypertension in self-reported never smokers verified by cotinine

- Association between the Urine Cotinine Level and Blood Pressure in Korean Adults with Secondhand Smoke Exposure: Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey 2016–2018

- Estimation of Secondhand Smoke Exposure in Clubs Based on Urinary Cotinine Levels