Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2012 Dec;5(4):213-217. 10.3342/ceo.2012.5.4.213.

What is the Relationship between the Localization of Maxillary Fungal Balls and Intranasal Anatomic Variations?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. entkbg@gmail.com

- KMID: 1489081

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3342/ceo.2012.5.4.213

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Although the mechanisms underlying the initiation and maintenance of inflammation in unilateral maxillary fungal balls (FBs) are poorly understood, the relationship between intranasal anatomy and maxillary FB is thought to play an important role. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between anatomic variations and FB.

METHODS

We enrolled 140 patients who were composed of 56 patients with FB, 56 patients with unilateral chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), and 28 patients with no sinus disease. Computed tomography scans were retrospectively analyzed to identify and compare the associated nasal anatomic abnormalities. To measure the volume of the nasal cavity and middle meatus, computed tomography scans were reconstructed into three-dimensional images.

RESULTS

The relatively larger volume of the middle meatus was associated with the localization of the FB in contrast with the CRS. However, the nasal-cavity volume, nasal valve area, and nasal septal deviation were not significantly associated with localization of FB. The mean volumetric and areal measurements such as nasal cavity, middle meatus, and nasal valve in FB-ipsilateral sides were not significantly different from those in contralateral sides as well as other groups.

CONCLUSION

The middle meatus bears the major part of the inspiratory nasal airflow, and its volume may influence the occurrence of FB.

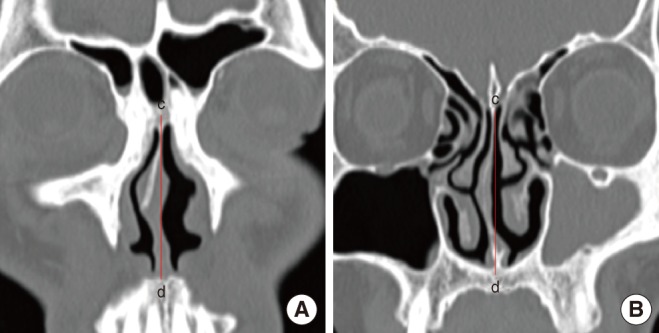

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Do Anatomical Variations Affect the Location of Solitary Sphenoid Sinus Fungal Balls? A 10-Year Retrospective Study

Jeon Gang Doo, Hye Kyu Min, Jin-Young Min

J Rhinol. 2024;31(1):22-28. doi: 10.18787/jr.2024.00001.

Reference

-

1. Lee KC. Clinical features of the paranasal sinus fungus ball. J Otolaryngol. 2007; 10. 36(5):270–273. PMID: 17963665.2. Broglie MA, Tinguely M, Holzman D. How to diagnose sinus fungus balls in the paranasal sinus? An analysis of an institution's cases from January 1999 to December 2006. Rhinology. 2009; 12. 47(4):379–384. PMID: 19936362.

Article3. Stammberger H. Endoscopic surgery for mycotic and chronic recurring sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1985; Sep-Oct. 119:1–11. PMID: 3931533.

Article4. Eloy P, Bertrand B, Rombeaux P, Delos M, Trigaux JP. Mycotic sinusitis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1997; 4. 51(4):339–352. PMID: 9444380.5. Tsai TL, Guo YC, Ho CY, Lin CZ. The role of ostiomeatal complex obstruction in maxillary fungus ball. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006; 3. 134(3):494–498. PMID: 16500452.

Article6. Boyce J, Eccles R. Do chronic changes in nasal airflow have any physiological or pathological effect on the nose and paranasal sinuses? A systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006; 2. 31(1):15–19. PMID: 16441795.

Article7. Gotwald TF, Zinreich SJ, Corl F, Fishman EK. Three-dimensional volumetric display of the nasal ostiomeatal channels and paranasal sinuses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001; 1. 176(1):241–245. PMID: 11133575.

Article8. Jiang RS, Su MC, Liao CY, Lin JF. Bacteriology of chronic sinusitis in relation to middle meatal secretion. Am J Rhinol. 2006; Mar-Apr. 20(2):173–176. PMID: 16686382.

Article9. Gillespie MB, O'Malley BW Jr, Francis HW. An approach to fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis in the immunocompromised host. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998; 5. 124(5):520–526. PMID: 9604977.

Article10. Adelson RT, Marple BF. Fungal rhinosinusitis: state-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment. J Otolaryngol. 2005; 6. 34 Suppl 1:S18–S23. PMID: 16089236.11. Helal MZ, El-Tarabishi M, Magdy Sabry S, Yassin A, Rabie A, Lin SJ. Effects of rhinoplasty on the internal nasal valve: a comparison between internal continuous and external perforating osteotomy. Ann Plast Surg. 2010; 5. 64(5):649–657. PMID: 20395791.12. Ural A, Kanmaz A, Inancli HM, Imamoglu M. Association of inferior turbinate enlargement, concha bullosa and nasal valve collapse with the convexity of septal deviation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010; 2. 130(2):271–274. PMID: 19479453.

Article13. Jun BC, Kim SW, Kim SW, Cho JH, Park YJ, Yoon HR. Is turbinate surgery necessary when performing a septoplasty? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009; 7. 266(7):975–980. PMID: 19002479.

Article14. Hooper RG. Nasal airflow in sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2004; 7. 126(1):316–317. PMID: 15249483.

Article15. Jun BC, Song SW, Kim BG, Kim BY, Seo JH, Kang JM, et al. A comparative analysis of intranasal volume and olfactory function using a three-dimensional reconstruction of paranasal sinus computed tomography, with a focus on the airway around the turbinates. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010; 9. 267(9):1389–1395. PMID: 20213157.

Article16. Kim HJ, Cho MJ, Lee JW, Kim YT, Kahng H, Kim HS, et al. The relationship between anatomic variations of paranasal sinuses and chronic sinusitis in children. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006; 10. 126(10):1067–1072. PMID: 16923712.17. Yasan H, Dogru H, Baykal B, Doner F, Tuz M. What is the relationship between chronic sinus disease and isolated nasal septal deviation? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005; 8. 133(2):190–193. PMID: 16087012.

Article18. Elahi MM, Frenkiel S. Septal deviation and chronic sinus disease. Am J Rhinol. 2000; May-Jun. 14(3):175–179. PMID: 10887624.

Article19. Garcia GJ, Rhee JS, Senior BA, Kimbell JS. Septal deviation and nasal resistance: an investigation using virtual surgery and computational fluid dynamics. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010; Jan-Feb. 24(1):e46–e53. PMID: 20109325.

Article20. Simmen D, Scherrer JL, Moe K, Heinz B. A dynamic and direct visualization model for the study of nasal airflow. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 9. 125(9):1015–1021. PMID: 10488989.

Article21. Wagenmann M, Naclerio RM. Anatomic and physiologic considerations in sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992; 9. 90(3 Pt 2):419–423. PMID: 1527330.

Article22. Sun Y, Dong Z, Yang Z. Study on the clearance function of mucociliary system in nasal middle meatus. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2002; 10. 16(10):530–532. PMID: 15515561.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Do Anatomical Variations Affect the Location of Solitary Sphenoid Sinus Fungal Balls? A 10-Year Retrospective Study

- A Case of Multiple Fungal Balls Involving the Isolated Three Sinuses

- Anatomic Variations of the Paranasal Sinus in Children with Chronic Sinusitis

- A Case of Fungal Ball Accompanied with a Microplate as Metallic Foreign Body in Maxillary Sinus

- A Case of Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis with Concurrently Occuring Fungus Ball