Korean J Perinatol.

2013 Mar;24(1):11-19. 10.14734/kjp.2013.24.1.11.

Changing Patterns of Congenital Anomalies over Ten Years in a Single Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Asan Medical Center Children's Hospital, University of Ulsan, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. arkim@amc.seoul.kr

- KMID: 1427067

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14734/kjp.2013.24.1.11

Abstract

- PURPOSE

To investigate incidence, changing patterns, and mortality associated with congenital anomalies experienced in a single neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

METHODS

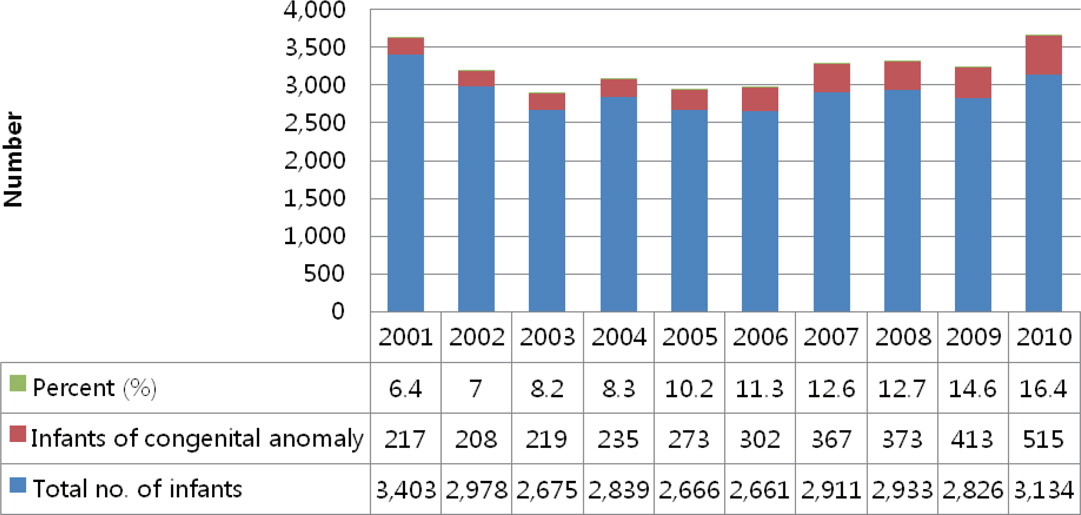

Retrospective chart review of 29,026 neonates admitted to NICU and nursery of Asan Medical Center from January 2001 to December 2010 was done. The congenital anomalies were classified according to 76 anomalies in 8 systems registered by Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2009.

RESULTS

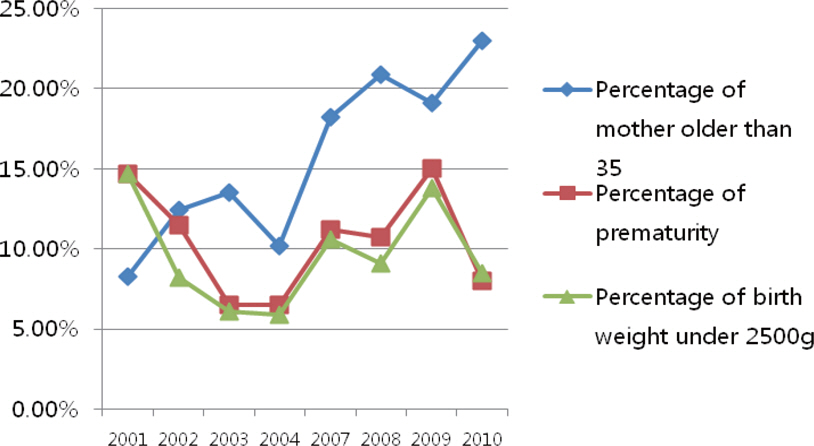

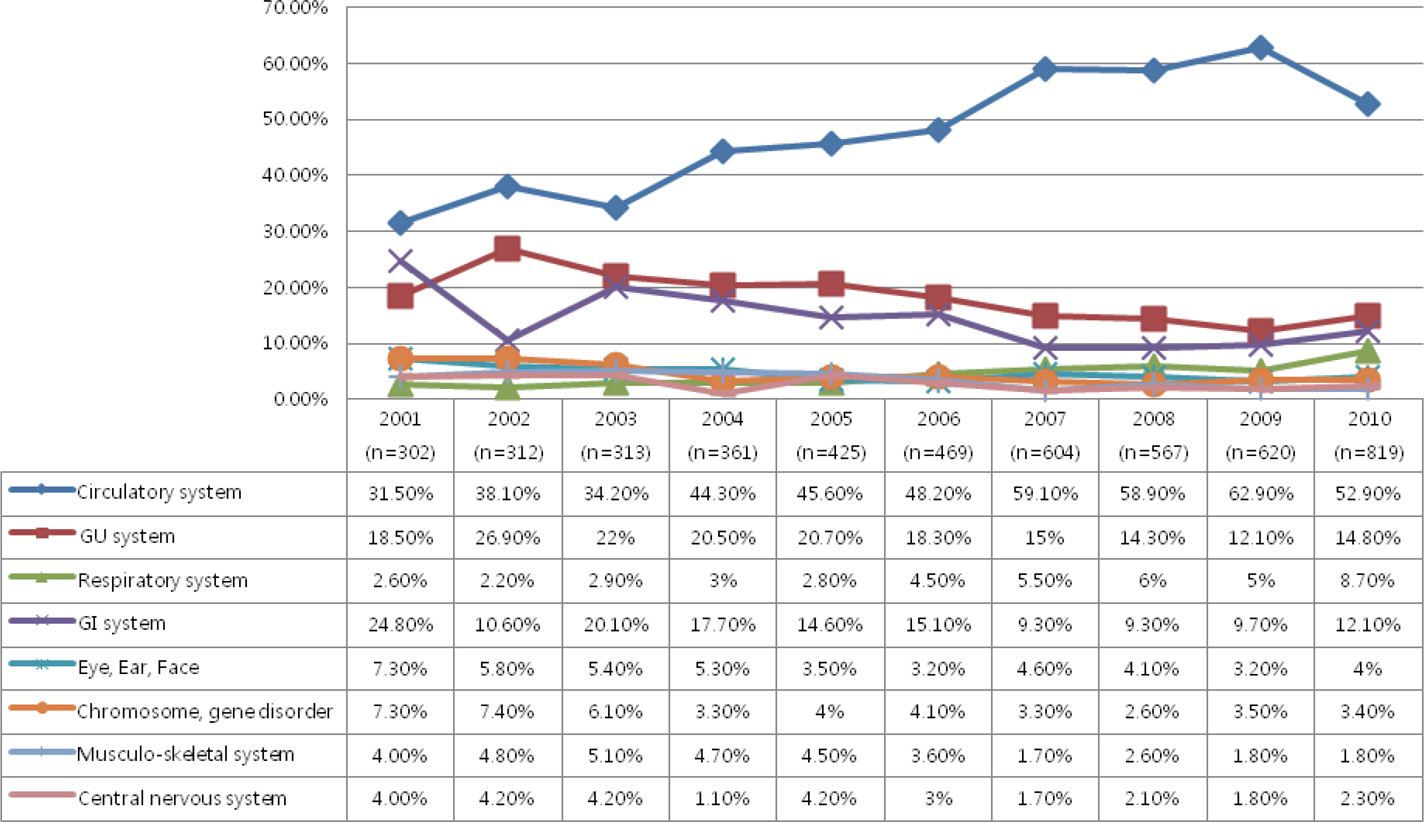

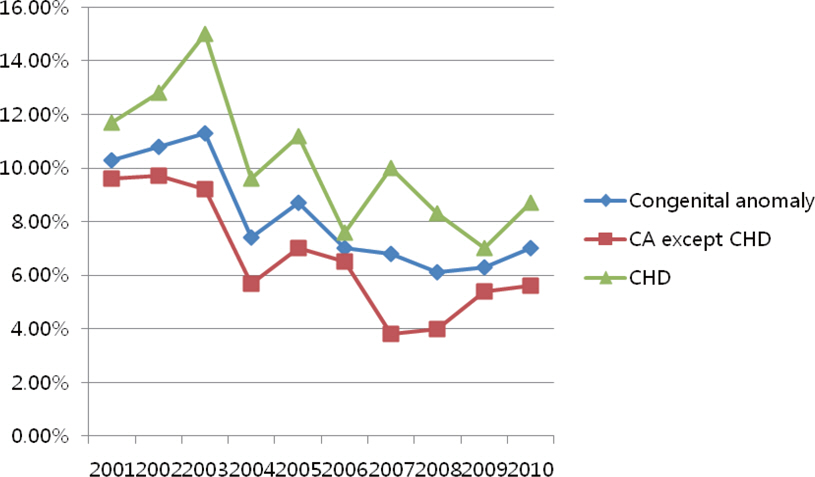

A total of 3,122 neonates had at least 1 anomaly. Mean gestational age and birth weight were 38(+2)+/-2.3 weeks and 2,030+/-541 g respectively. The proportion of male is 61%. The incidence of congenital anomalies and the proportion of mothers older than 35 years increased from 8.3% to 23.0% and 6.4% to 16.4% in 2001 compared to 2010 respectively. The percentage of neonates who have multiple anomalies was almost equal from 24.0% in 2001 to 23.7% in 2010. The most common anomalies, by system, included atrial septal defect, hydronephrosis, anorectal atresia/stenosis, cystic adenomatoid malformation, cleft lip and/or palate, CATCH 22 syndrome, polydactyly, and hydrocephalus. The overall mortality at 2 years old decreased from 11.1% to 8.0% in 2001 and 2010. Most common etiologies resulting in highest mortality, by system, were hypoplastic left heart syndrome, renal agenesis, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, pulmonary hypoplasia, 18 trisomy, and anancephaly.

CONCLUSION

Our data have shown that the incidence of congenital anomaly included in this study is increasing. A detailed epidemiologic study based on larger population is required in order to investigate preventive measures.

MeSH Terms

-

Birth Weight

Cleft Lip

Congenital Abnormalities

Epidemiologic Studies

Gestational Age

Heart Septal Defects, Atrial

Hernia, Diaphragmatic

Humans

Hydrocephalus

Hydronephrosis

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

Incidence

Infant, Newborn

Intensive Care, Neonatal

Kidney

Kidney Diseases

Male

Mothers

Nurseries

Palate

Polydactyly

Retrospective Studies

Trisomy

Congenital Abnormalities

Hernia, Diaphragmatic

Kidney

Kidney Diseases

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Admission of Term Infants to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit from Nursery

Jin Seok Park, Kee Hyun Cho, Heui Seung Jo, Sung-Il Cho, Gyu Young Chae, Moon Kyu Kim, Kyu Hyung Lee

Korean J Perinatol. 2014;25(4):246-256. doi: 10.14734/kjp.2014.25.4.246.

Reference

-

1). Yoon PW., Rasmussen SA., Lynberg MC., Moore CA., Anderka M., Carmichael SL, et al. The National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Public Health Rep. 2001. 116:Suppl.

Article2). Chung SH., Choi YS., Bae CW. Changes in the neonatal and infant mortality rate and the causes of death in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2011. 54:443–55.

Article3). Kim SK., Han HJ., Son SS., Hong SK., Hwang SU. A clinical review of congenital anomalies in newborn infants. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1984. 27:781–8.4). Kim HJ., Kim CG., Ju GS. Clinical study for congenital anomalies in the newborn infants. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1988. 31:248–55.5). Choi JH., Chung HJ., Yoon JG. Clinical studies on congenital malformations. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1985. 28:74–81.6). Lee HW., Whang IG., Lee KW., Kang JS. Clinical study of the congenital anomalies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1990. 33:754–62.7). Hwang CG., Lim BH., Kim KB. A clinical review of congenital anomalies in neonates. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1988. 31:306–14.8). Kwon YS., Oh HK., Kim JJ., Soh CO., Jung JH., Jung JY. Clinical study on congenital anomalies. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1992. 35:315–21.9). Yang YJ., Jung JY., Park SG. Statistical study on congenital anomalies. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 1997. 4:170–7.10). Kim YW., Kim SJ., Hur SY., Lee GSR., Lee Y., Kim EJ, et al. The clinical study of congenital anomalies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 41:1698–703.11). Koh KS., Kim A., Yang SH., Han JY., Kim ES., Kim MY, et al. Multi-center study for birth defects monitoring systems in Korea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 44:1609–16.12). Jin K., Kim JS., Koh KS., Park CH. Clinical analysis of fetal congenital anomalies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 45:32–44.13). Kang BH., Lee JG., Chung KH., Yang JB., Kim DY., Rhee YE, et al. Incidence of congenital anomalies and diagnosis of congenital anomalies by antenatal ultrasonography. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004. 47:2070–6.14). Choi JS., Seo K., Hahn YJ., Lee SW., Boo YG., Lee SW, et al. Congenital anomaly survey and statistics. Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2009.15). Tennant PW., Pearce MS., Bythell M., Rankin J. 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010. 375:649–56.

Article16). Brent RL. Addressing environmentally caused human birth defects. Pediatr Rev. 2001. 22:153–65.

Article17). Garne E., Loane M., Wellesley D. Barisic I and a EUROCAT Working Group. Congenital hydronephrosis: prenatal diagnosis and epidemiology in Europe. J Pediatr Urol. 2009. 5:47–52.

Article18). Garnea E., Loaneb M., Addorc MC., Boydd PA., Barisice I., Dolkb H. Congenital hydrocephalus - prevalence, prenatal diagnosis and outcome of pregnancy in four European regions. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010. 14:150–5.19). Warkany J., Kalter H. Congenital malformations. N Engl J Med. 1961. 265:993–1001.

Article20). Marden PM., Smith DW., McDonald MJ. Congenital anomalies in the newborn infant, including minor variations. Pediatrics. 1964. 64:357–71.21). Cho JS., Kim KS., Kim SY., Kim TY., Choi HM., Lim YG, et al. Congenital anomalies diagnosed by antenatal ultrasonography. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 40:1228–32.22). Bae CW. Neonatal epidemiology in Korea.23). Kim A., Kim SR., Yang SH., Han JY., Kim MY., Yang JH, et al. Multi-center study for birth defects monitoring systems in Korea. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 45:1924–31.24). Kalter H. Five-decade international trends in the relation of perinatal mortality and congenital malformations: stillbirth and neonatal death compared. Int J Epidemiol. 1991. 20:173–9.

Article25). Wang Y., Hu J., Druschel CM. A retrospective cohort study of mortality among children with birth defects in New York State, 1983-2006. Birth Defects Res A clin Mol Teratol. 2010. 88:1023–31.

Article26). National Birth Defects Prevention Network (NBDPN). State birth defects surveillance program directory. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009. 85:1007–55.27). EUROCAT. EUROCAT Special Report: Prenatal Screening Policies in Europe. EUROCAT Central Registry, University of Ulster. 2005.28). Wellesley D., Boyd P., Dolk H., Pattenden S. An aetiological classification of birth defects for epidemiological research. J Med Genet. 2005. 42:54–7.

Article29). International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research. International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research Annual report 2008. Roma, Italy: The International Centre on Birth Defects - ICBDSR Centre. 2008.30). Wen SW., Liu S., Joseph KS., Rouleau J., Allen A. Patterns of infant mortality caused by congenital anomalies. Teratology. 2000. 61:342–6.31). Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare. Infant mortality survey report in. 2011.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Management of Cyanotic Congenital Heart Defect in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

- Death in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- Organisation of Special and Intensive Care Facilities for Babies

- Quality Improvement in Neonatal Intensive Care Units

- Frequency of Neurologic Disorders in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Associated Factors