Korean J Radiol.

2011 Oct;12(5):611-619. 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.611.

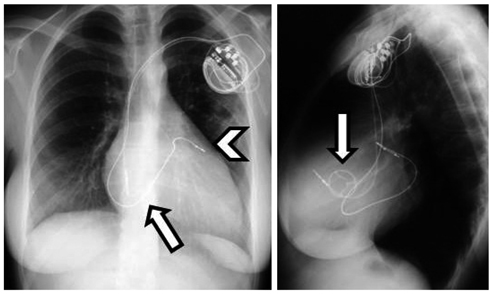

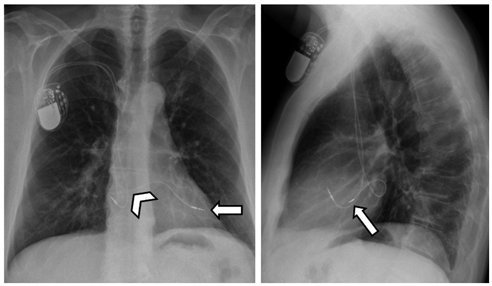

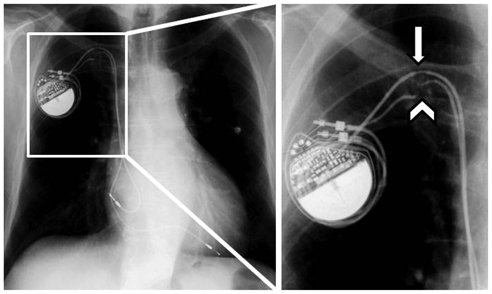

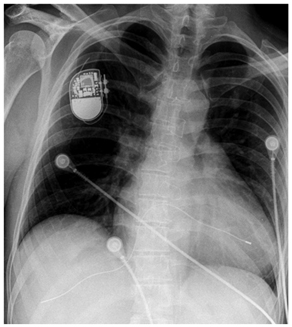

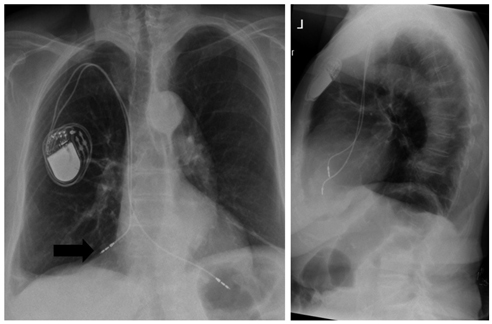

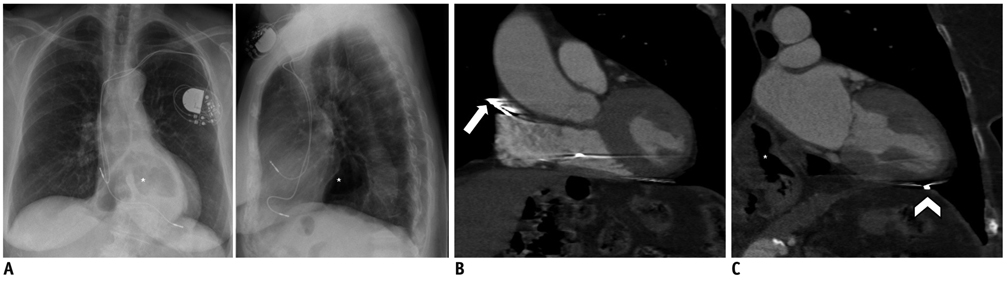

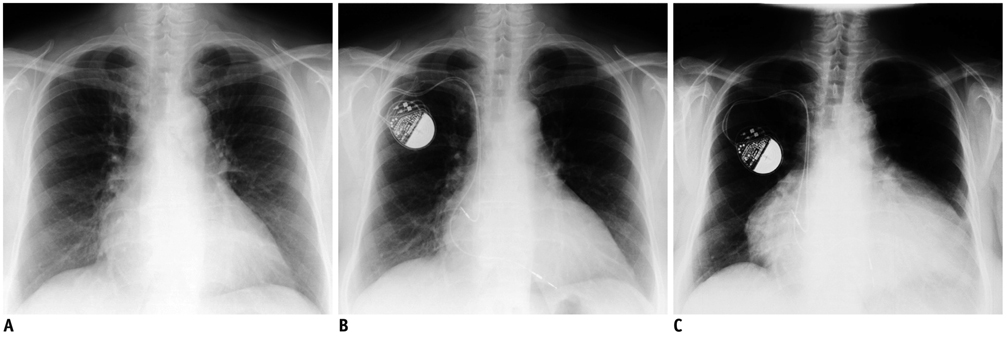

Where Does It Lead? Imaging Features of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices on Chest Radiograph and CT

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University of Duesseldorf, Medical Faculty, 40225 Dusseldorf, Germany. pkroepil@gmx.de

- 2Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, University Hospital Dusseldorf, 40225 Dusseldorf, Germany.

- 3Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

- KMID: 1116447

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2011.12.5.611

Abstract

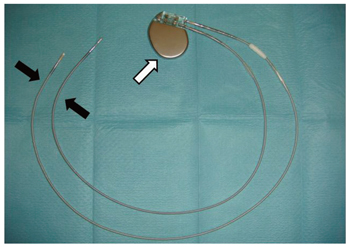

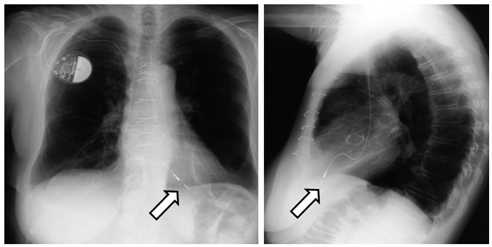

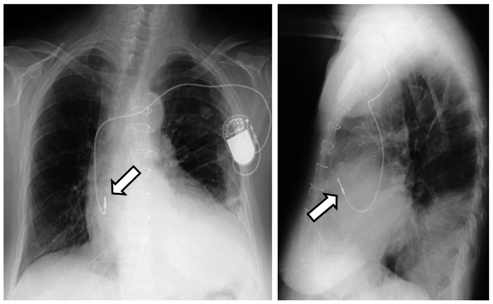

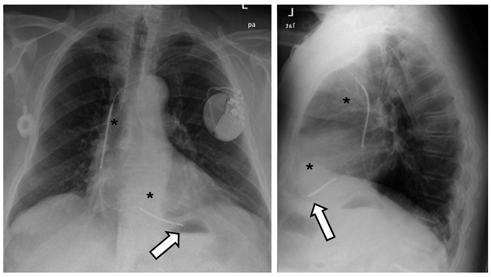

- Pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) are being increasingly employed in patients suffering from cardiac rhythm disturbances. The principal objective of this article is to familiarize radiologists with pacemakers and ICDs on chest radiographs and CT scans. Therefore, the preferred lead positions according to pacemaker types and anatomic variants are introduced in this study. Additionally, the imaging features of incorrect lead positions and defects, as well as complications subsequent to pacemaker implantation are demonstrated herein.

Keyword

- Pacemaker; ICD; Chest; Radiograph; CT

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Borek PP, Wilkoff BL. Pacemaker and ICD leads: strategies for long-term management. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2008. 23:59–72.2. Grier D, Cook PG, Hartnell GG. Chest radiographs after permanent pacing. Are they really necessary? Clin Radiol. 1990. 42:244–224.3. Heldman D, Mulvihill D, Nguyen H, Messenger JC, Rylaarsdam A, Evans K, et al. True incidence of pacemaker syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1990. 13:1742–1750.4. Markewitz A. [Yearly report for 2007 of the German Pacemaker registry]. Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol. 2008. 19:195–223.5. Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004. 350:2140–2150.6. Connolly SJ, Hallstrom AP, Cappato R, Schron EB, Kuck KH, Zipes DP, et al. Meta-analysis of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator secondary prevention trials. AVID, CASH and CIDS studies. Antiarrhythmics vs Implantable Defibrillator study. Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg. Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study. Eur Heart J. 2000. 21:2071–2078.7. Ratliff HL, Yousufuddin M, Lieving WR, Watson BE, Malas A, Rosencrance G, et al. Persistent left superior vena cava: case reports and clinical implications. Int J Cardiol. 2006. 113:242–246.8. Jokinen JJ, Turpeinen AK, Pitkanen O, Hippelainen MJ, Hartikainen JE. Pacemaker therapy after tricuspid valve operations: implications on mortality, morbidity, and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009. 87:1806–1814.9. Moons P, Gewillig M, Sluysmans T, Verhaaren H, Viart P, Massin M, et al. Long term outcome up to 30 years after the Mustard or Senning operation: a nationwide multicentre study in Belgium. Heart. 2004. 90:307–313.10. Pakarinen S, Oikarinen L, Toivonen L. Short-term implantation-related complications of cardiac rhythm management device therapy: a retrospective single-centre 1-year survey. Europace. 2010. 12:103–108.11. Wiegand UK, LeJeune D, Boguschewski F, Bonnemeier H, Eberhardt F, Schunkert H, et al. Pocket hematoma after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator surgery: influence of patient morbidity, operation strategy, and perioperative antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. Chest. 2004. 126:1177–1186.12. Burney K, Burchard F, Papouchado M, Wilde P. Cardiac pacing systems and implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs): a radiological perspective of equipment, anatomy and complications. Clin Radiol. 2004. 59:699–708.13. Aggarwal RK, Connelly DT, Ray SG, Ball J, Charles RG. Early complications of permanent pacemaker implantation: no difference between dual and single chamber systems. Br Heart J. 1995. 73:571–575.14. Edwards NC, Varma M, Pitcher DW. Routine chest radiography after permanent pacemaker implantation: is it necessary? J Postgrad Med. 2005. 51:92–96. discussion 96-97.15. Castillo R, Cavusoglu E. Twiddler's syndrome: an interesting cause of pacemaker failure. Cardiology. 2006. 105:119–121.16. Magney JE, Flynn DM, Parsons JA, Staplin DH, Chin-Purcell MV, Milstein S, et al. Anatomical mechanisms explaining damage to pacemaker leads, defibrillator leads, and failure of central venous catheters adjacent to the sternoclavicular joint. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993. 16:445–457.17. Connolly SJ, Gent M, Roberts RS, Dorian P, Roy D, Sheldon RS, et al. Canadian implantable defibrillator study (CIDS) : a randomized trial of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator against amiodarone. Circulation. 2000. 101:1297–1302.18. Roelke M, O'Nunain SS, Osswald S, Garan H, Harthorne JW, Ruskin JN. Subclavian crush syndrome complicating transvenous cardioverter defibrillator systems. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1995. 18:973–979.19. Mahapatra S, Bybee KA, Bunch TJ, Espinosa RE, Sinak LJ, McGoon MD, et al. Incidence and predictors of cardiac perforation after permanent pacemaker placement. Heart Rhythm. 2005. 2:907–911.20. Kiviniemi MS, Pirnes MA, Eranen HJ, Kettunen RV, Hartikainen JE. Complications related to permanent pacemaker therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999. 22:711–720.21. Ho WJ, Kuo CT, Lin KH. Right pneumothorax resulting from an endocardial screw-in atrial lead. Chest. 1999. 116:1133–1134.22. Hirschl DA, Jain VR, Spindola-Franco H, Gross JN, Haramati LB. Prevalence and characterization of asymptomatic pacemaker and ICD lead perforation on CT. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007. 30:28–32.23. Snow ME, Agatston AS, Kramer HC, Samet P. The postcardiotomy syndrome following transvenous pacemaker insertion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1987. 10:934–936.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Experiences of magnetic resonance imaging scanning in patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators

- Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Hematoma Prevention Using Tachosil (Fibrin Sealant) Patch during Insertion of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices without Suspending Antithrombotics: Three Case Reports

- Efforts of the Past 20 Years for Proved Magnetic Resonance Imaging Safety of Medtronic Implantable Cardiac Devices

- Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Safety during Magnetic Resonance Imaging