J Rheum Dis.

2024 Apr;31(2):86-96. 10.4078/jrd.2023.0045.

Real-world effectiveness of a single conventional diseasemodifying anti-rheumatic drug (cDMARD) plus an anti-TNF agent versus multiple cDMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective observational study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Yangsan, Korea

- 2Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 3Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea

- 4Department of Rheumatology, Hanyang University Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Seoul, Korea

- 5Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 6Department of Internal Medicine and Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine and Hospital, Jinju, Korea

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Eulji University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University Guri Hospital, Guri, Korea

- 9Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 10Medical Department, MSL, Eisai Korea Inc., Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2554324

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4078/jrd.2023.0045

Abstract

Objective

The objective of this prospective, observational multicenter study (NCT03264703) was to compare the effectiveness of single conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (cDMARD) plus anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy versus multiple cDMARD treatments in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) following cDMARD failure in the real-world setting in South Korea.

Methods

At the treating physicians’ discretion, patients received single cDMARD plus anti-TNF therapy or multiple cDMARDs. Changes from baseline in disease activity score 28-joint count with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR), corticosteroid use, and Korean Health Assessment Questionnaire (KHAQ-20) scores were evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Results

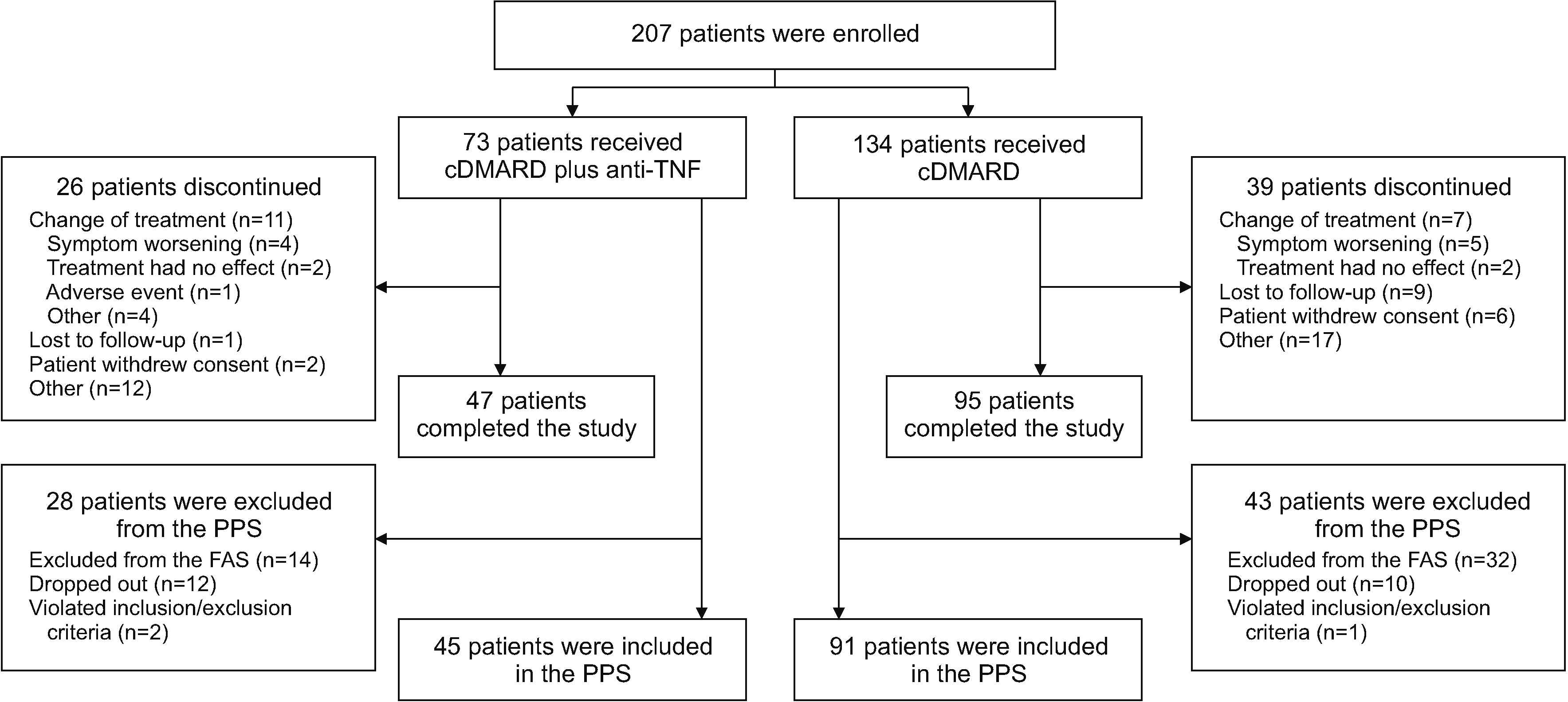

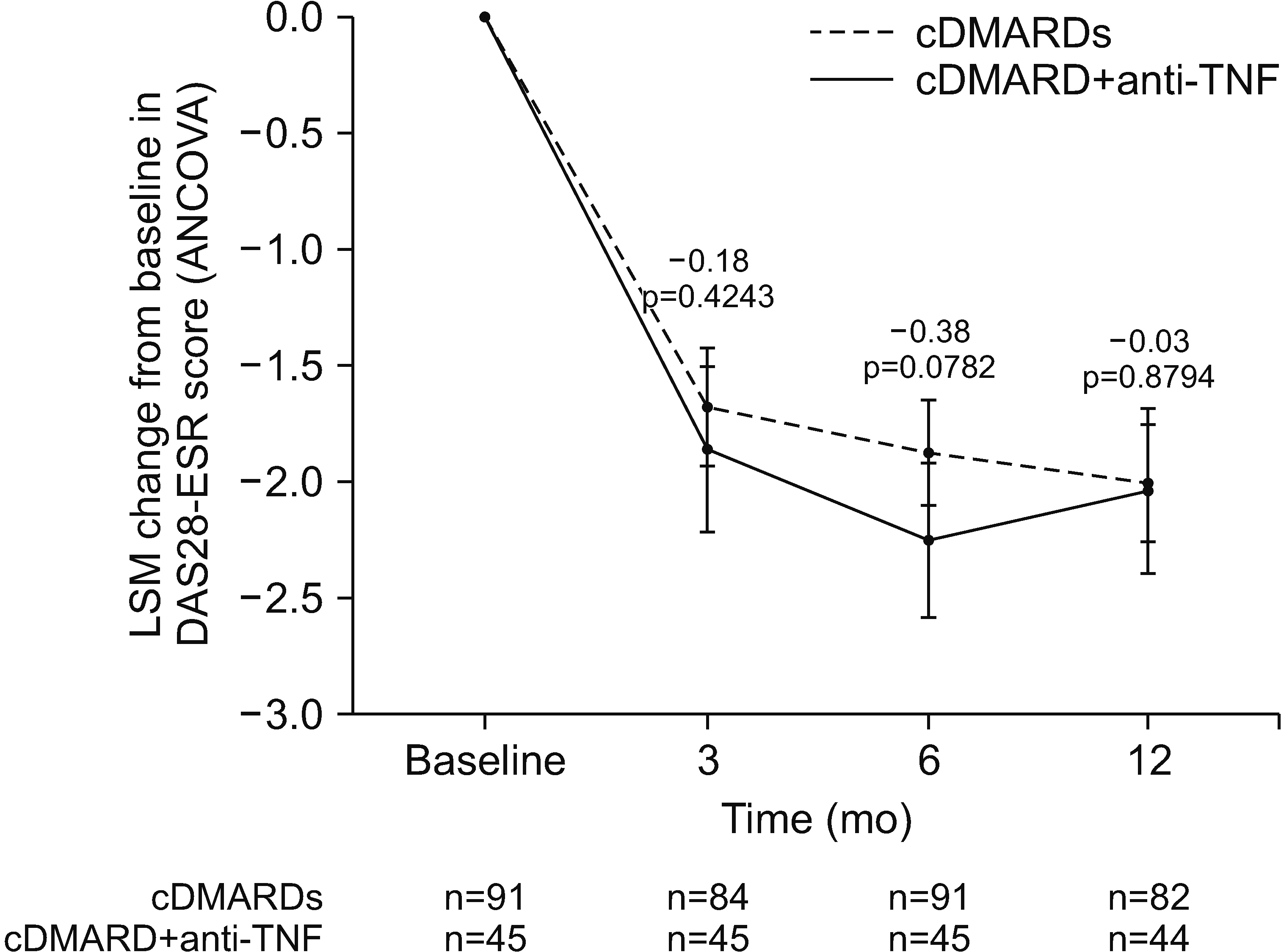

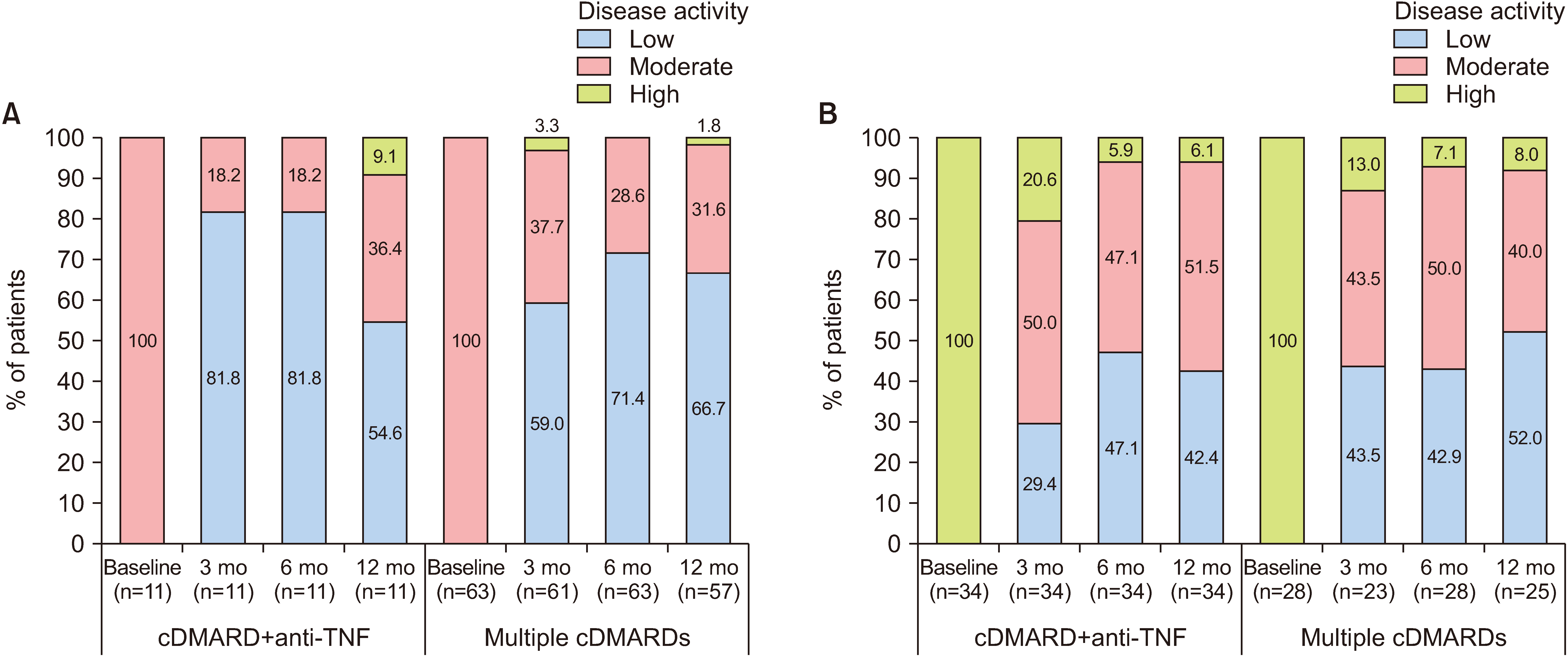

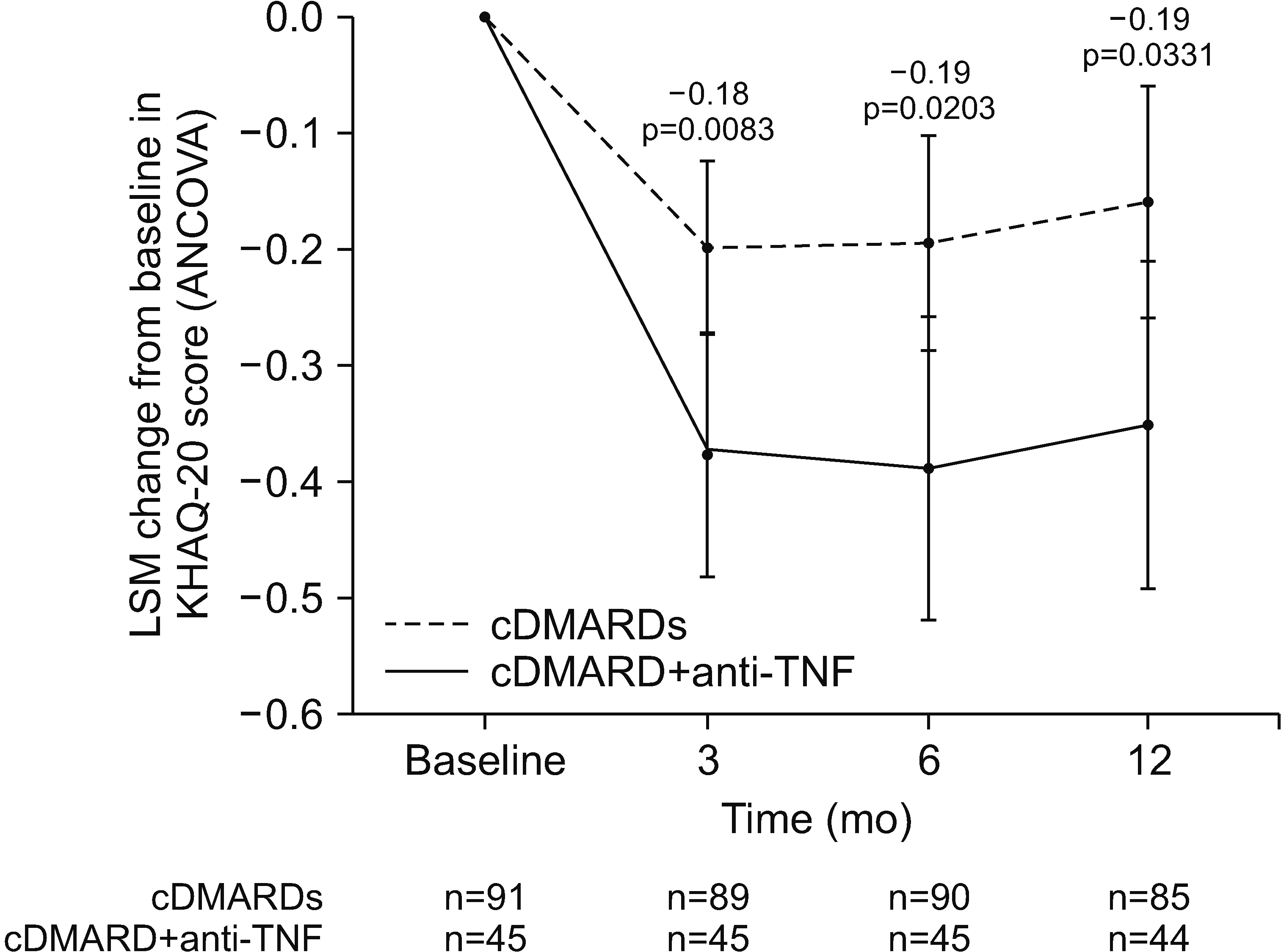

Of 207 enrollees, the final analysis included 45 of 73 cDMARD plus anti-TNF and 91 of 134 multiple-cDMARD recipients. There were no significant between-group differences (BGDs) in ANCOVA-adjusted changes from baseline in DAS28-ESR at 3, 6 (primary endpoint), and 12 months (BGDs −0.18, −0.38, and −0.03, respectively). More cDMARD plus anti-TNF than multiple-cDMARD recipients achieved a >50% reduction from baseline in corticosteroid dosage at 12 months (35.7% vs 14.6%; p=0.007). Changes from baseline in KHAQ-20 scores at 3, 6, and 12 months were significantly better with cDMARD plus antiTNF therapy than with multiple cDMARDs (BGD −0.18, −0.19, and −0.19 points, respectively; all p≤0.024).

Conclusion

In the real-world setting, relative to multiple cDMARDs, single cDMARD plus anti-TNF therapy significantly improved quality-of-life scores and reduced corticosteroid use, with no significant BGD in disease activity, in RA patients in whom previous cDMARD therapy had failed.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Calabresi E, Petrelli F, Bonifacio AF, Puxeddu I, Alunno A. 2018; One year in review 2018: pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 36:175–84.2. Won S, Cho SK, Kim D, Han M, Lee J, Jang EJ, et al. 2018; Update on the prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Korea and an analysis of medical care and drug utilization. Rheumatol Int. 38:649–56. DOI: 10.1007/s00296-017-3925-9. PMID: 29302803.

Article3. Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, St Clair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, et al. 2021; 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 73:924–39. DOI: 10.1002/acr.24596. PMID: 34101387. PMCID: PMC9273041.

Article4. Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bergstra SA, Kerschbaumer A, Sepriano A, Aletaha D, et al. 2023; EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 82:3–18. Erratum in: Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:e76. DOI: 10.1136/ard-2022-223356corr1. PMID: 36764818.5. 2021. Jul. 6. Xeljanz (tofacitinib): increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies with use of tofacitinib relative to TNF-alpha inhibitors [Internet]. European Medicines Agency;Amsterdam: Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/dhpc/xeljanz-tofacitinib-increased-risk-major-adverse-cardiovascular-events-malignancies-use-tofacitinib. cited 2023 Jul 5.6. Ma MH, Kingsley GH, Scott DL. 2010; A systematic comparison of combination DMARD therapy and tumour necrosis inhibitor therapy with methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 49:91–8. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep331. PMID: 19917618.

Article7. Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T, Faurschou M, Baslund B, Jürgens G. 2015; Combination therapy with and without tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 67:1487–95. DOI: 10.1002/acr.22618. PMID: 25989246.

Article8. Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T, Tarp S, Christensen R, Jürgens G. 2014; Effect of combination therapy on joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 9:e106408. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106408. PMID: 25244021. PMCID: PMC4171366.

Article9. Curtis JR, Palmer JL, Reed GW, Greenberg J, Pappas DA, Harrold LR, et al. 2021; Real-world outcomes associated with methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine triple therapy versus tumor necrosis factor inhibitor/methotrexate combination therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 73:1114–24. DOI: 10.1002/acr.24253. PMID: 32374918.

Article10. Bergstra SA, Winchow LL, Murphy E, Chopra A, Salomon-Escoto K, Fonseca JE, et al. 2019; How to treat patients with rheumatoid arthritis when methotrexate has failed? The use of a multiple propensity score to adjust for confounding by indication in observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 78:25–30. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213731. PMID: 30327328.

Article11. van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. van 't Hof MA. 1996; Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 39:34–40. DOI: 10.1002/art.1780390105. PMID: 8546736.

Article12. Nishimoto N, Takagi N. 2010; Assessment of the validity of the 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) as a disease activity index of rheumatoid arthritis in the efficacy evaluation of 24-week treatment with tocilizumab: subanalysis of the SATORI study. Mod Rheumatol. 20:539–47. DOI: 10.3109/s10165-010-0328-0. PMID: 20617358. PMCID: PMC2999727.

Article13. Fransen J, van Riel PL. 2009; The Disease Activity Score and the EULAR response criteria. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 35:745–57. vii–viii. DOI: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.10.001. PMID: 19962619.

Article14. Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann RM, Emery P, Kupper H, Redden L, Guerette B, et al. 2013; Clinical, functional and radiographic consequences of achieving stable low disease activity and remission with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone in early rheumatoid arthritis: 26-week results from the randomised, controlled OPTIMA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 72:64–71. DOI: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201247. PMID: 22562973. PMCID: PMC3551224.

Article15. Kay J, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B, Nash P, Durez P, Hall S, et al. 2008; Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment with methotrexate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum. 58:964–75. Erratum in: Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3518. DOI: 10.1002/art.23383. PMID: 18383539.

Article16. Atzeni F, Talotta R, Salaffi F, Cassinotti A, Varisco V, Battellino M, et al. 2013; Immunogenicity and autoimmunity during anti-TNF therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 12:703–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.021. PMID: 23207283.

Article17. Anderson PJ. 2005; Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: clinical implications of their different immunogenicity profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 34(5 Suppl 1):19–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.005. PMID: 15852250.

Article18. Sode J, Vogel U, Bank S, Andersen PS, Hetland ML, Locht H, et al. 2018; Confirmation of an IRAK3 polymorphism as a genetic marker predicting response to anti-TNF treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacogenomics J. 18:81–6. DOI: 10.1038/tpj.2016.66. PMID: 27698401.

Article19. Scott DL, Ibrahim F, Farewell V, O'Keeffe AG, Walker D, Kelly C, et al. 2015; Tumour necrosis factor inhibitors versus combination intensive therapy with conventional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in established rheumatoid arthritis: TACIT non-inferiority randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 350:h1046. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h1046. PMID: 25769495. PMCID: PMC4358851.

Article20. Berardicurti O, Ruscitti P, Pavlych V, Conforti A, Giacomelli R, Cipriani P. 2020; Glucocorticoids in rheumatoid arthritis: the silent companion in the therapeutic strategy. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 13:593–604. DOI: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1772055. PMID: 32434398.

Article21. Hua C, Buttgereit F, Combe B. 2020; Glucocorticoids in rheumatoid arthritis: current status and future studies. RMD Open. 6:e000536. DOI: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000536. PMID: 31958273. PMCID: PMC7046968.

Article22. Pope JE, Khanna D, Norrie D, Ouimet JM. 2009; The minimally important difference for the health assessment questionnaire in rheumatoid arthritis clinical practice is smaller than in randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 36:254–9. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.080479. PMID: 19132791.

Article23. Cho SK, Bae SC. 2017; Pharmacologic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Korean Med Assoc. 60:156–63. DOI: 10.5124/jkma.2017.60.2.156.

Article24. Heckman MG, Davis JM 3rd, Crowson CS. 2022; Post hoc power calculations: an inappropriate method for interpreting the findings of a research study. J Rheumatol. 49:867–70. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.211115. PMID: 35105710.

Article25. Fraser RA. 2023; Inappropriate use of statistical power. Bone Marrow Transplant. 58:474–7. DOI: 10.1038/s41409-023-01935-3. PMID: 36869191.

Article26. Giacomelli R, Afeltra A, Bartoloni E, Berardicurti O, Bombardieri M, Bortoluzzi A, et al. 2021; The growing role of precision medicine for the treatment of autoimmune diseases; results of a systematic review of literature and Experts' Consensus. Autoimmun Rev. 20:102738. DOI: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102738. PMID: 33326854.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Recurrent Pneumothorax after Etanercept Therapy in a Rheumatoid Arthritis Patient: A Case Report

- Persistence with Anti-TNF Therapies in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Comparative Effectiveness of Biologic DMARDs in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Inadequate Response to conventional DMARDs: Using a Bayesian Network Meta-analysis

- Update on rheumatoid arthritis

- Diagnostic Signification of Antiperinuclear Factor(APF) in Rheumatoid Arthritis